THE STRUCTURE OF. AIR POWER

Hitherto, air power theory has been the exclusive province of West European and United States’ theoreticians and experts. Attempts to formulate and explain air power date back to the infancy of aviation. Concepts of naval power provided starting points. Early air power theorists borrowed ideas and basic postulates from naval warfare fairly uncritically. This worked only occasionally.

The concept of naval power is firmly linked with Alfred Dyer Mahan. He defined naval power as the ability to use the seas for military aims, and thwart the enemy in doing the same. Mahan pointed out that the seas could be used not only as a setting in which to destroy enemy forces representing a genuine threat, but also as one in which to exercise indirect but nonetheless decisive influence on military potential. Mahan’s 1890 treatise, The Influence of Naval Power upon History, also contained the rather too absolute prescription of superiority as a prerequisite in all naval operations: nothing was to be undertaken before superiority was secured. What was needed was a large, centrally commanded fleet whose basic purpose was to destroy enemy capital forces.

Another naval strategy theorist, Sir Julian Corbett, regarded the high seas in their normal state as uncontrollable. His great contribution was to separate the attainment of superiority from its exercise, which he treated as a distinct aim of naval power. These twin aims in turn dictated different armaments, training, and unit structure. Specialists will readily find analogies with contemporary views of air power.

What is the nexus between naval power and air power? At the turn of the 20th Century, it was the striving to seek superiority or mastery in a largely uncontrollable environment. In addition, both naval an air power depended upon — and served the needs of — land operations. This gradually led to the triune configuration of national power, enabling nations to pursue their objectives not only on dry land, but also on the high seas, and in the air.

What were the properties of the new environment over which politicians and soldiers felt challenged to seek superiority?

The first and essential one is its universality. The earliest flying machines suggested to strategists that the new leap of human ingenuity had a future: with develop – ment, it would render any point on Earth accessible, moreover at speeds unknown to land and naval vehicles. Speed gave the new environment its second advantage: greater mobility, granting intrinsic privileges to owners of flying machines. The third advantage stems from the ability to move in three dimensions, thus gaining a large measure of invulnerability. Graf Zeppelin’s dirigibles and the Albatros Company’s aeroplanes

abruptly ended a British geographical immunity bestowed by 36 kilometres (21 miles) of English Channel. This immunity had held since the Norman Conquest in 1066, yet henceforth no nation was beyond invasion from the air.

Early flyers grasped the opportunities offered by the new environment (viz. Professor Charles’s views, and Orville Wright’s letters to his government almost a century hence). However, the first soldier and theoretician to state notions of the changes about to hit warfare, was Giulio Douhet. In 1909, this unknown artillery Maggiore wrote:

“It may well seem improbable that the sky shall turn into a battlefield no less important than the land and the seas. However, it would be better if we accept this probability now, and prepare our services for the conflicts to come. The struggle for aerial superiority shall be arduous, yet ostensibly civilised nations shall strive to prosecute war insistently, and with all means at their disposal.”[1]

By 1913, Colonele Tenente Douhet was firmly of the opinion that aerial forces must form a separate command. Criticising Italian high command strategy, he declared:

“Aerial space shall be independent. A new type of weaponry is being born: aerial weaponry. A new battlefield is being opened: the air. The history of warfare is being infused with a new factor: the principle of aerial warfare has been born.”2

The first military leader who not only saw the significance of nascent air power but also began active work to elevate it as a primary pillar of national power, was the Head of the German General Staff, General-Feldmarschall von Moltke. Before the First World War, he formulated and applied a programme for the promotion of this new weaponry, and for the creation of properly functioning Army and Navy air units.

During the Great War, Generals Trenchard and Mitchell were the first to breach the Klausewitz postulates on warfare (which Foche was following). British soldiers had principal differences with Klausewitz’s paradigms: they had attained and maintained a 150 year superiority not through set-piece wars but through manoeuvre, limited warfare, attrition and threat. Major General Trenchard and Brigadier Mitchell proved that rather than being tied to close support of the infantry, aerial forces ought to co-operate with them, yet pursue independent objectives.

Reviewing Tripolitanian, Balkan and Great War experience, Generale Douhet attempted the first definition of air power in his 1921 book, Command of the Air. He and subsequent theorists regarded air power merely as a tool for mastery, even after the advent of missiles. For instance, writing in the January 1956 issue of the Air Force Journal, Major Alexandre Seversky defined air power as a function of speed, height, range, mobility, and the ability to project armed power with pinpoint accuracy in time and place at maximum speed.

To this very moment, air power tends to be regarded as a component of national armed power. In this sense, its definitions tend to recycle general concepts of armed power and combat potential. Treating the airforce as a prime command, they address its armed power, combat potential, state, and ability to attain set objectives within a discrete timeframe.

However, there are grounds for believing that air power is in fact the rational combination of all means for operating in the air, and of all means for defending the national interest. Air power determines a country’s ability to harness the military and business benefits of the air for its own ends. In this sense, air power may also be defined as the extent to which national air potential is actualised: the extent to which the elements of national air potential are given tangible shape.

It is reasonable to regard air power as a system comprising components, links and dependencies. In unbreakable unity with their environment — the air — they display interrelationships that give the system its wholeness.

Specific historical conditions determine the significance of air power’s individual components. The dominating significance of its contents is a matter not only of today, but also of tomorrow. In the context of this volume, the military aspects of air power are particularly important, since your Author examines the current and future role of airforces in warfare.

The structure of the air power system is markedly hierarchical. It comprises basic components (ones instrumental in the performance of business or combat tasks), and elements influencing the performance of such tasks to one extent or another. The number of components and elements in the proposed system is not fixed. It, and the extent of their development, depend on a variety of factors and have a purely national character. These factors include, inter alia: degree of national economic development; priority objectives set before nations; major points in national military doctrines; and the political and geographical environment. For instance, most nations have chosen a tripartite armed forces structure; but some (like Israel, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam and former USSR) have a quadripartite structure, with air defence the fourth part. Nevertheless, the principles for determining the major components obtain for the force structures of any nation with aircraft and an infrastructure for their operation.

These basic components of air power have been nominated (Diagram 3):

– the Air Force (including air defence forces, with the proviso that in the aforementioned countries they are separate commands)

– state and private airlines and general aviation companies

– the naval air arm

– police and border patrol air units

– state and civic air clubs and voluntary defence support organisations

– the air traffic control system

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

– the entire air operations infrastructure

– the research and development (R&D), education and training (E&T), and manufacturing sectors.

A proper legislative base is crucial in delineating air power and ensuring normal function to its structures. While one cannot define it as a component of air power, it affects processes and task performance directly, particularly in peacetime.

One may regard each component of the air power system as a subsystem of constituent elements. For instance, airforces comprise units which discharge peace and wartime tasks. One may also regard aviation as one of these elements as a subsystem comprising types of aviation. However, your Author is loath to overanalyse the system and thus risk obfuscation.

Certain components of air power play a special role in its development. Therefore, they repay especial examination whose findings may be used as an entry point into the air power system. They are: the entire air operations infrastructure; R&D, E&T, and manufacturing.

Within the former, one may discern two basic elements: the repairs and maintenance sector, and the airports and airfields network. The R&D, E&T and manufacturing component comprises the entire national science and research establishment, the aviation industry, engineering design and consultancy bodies, and flying schools. Although here these elements rank as mere parts of larger components, and although their presence in most nations’ air power systems is token or nonexistent, their significance to flying and aviation is immense.

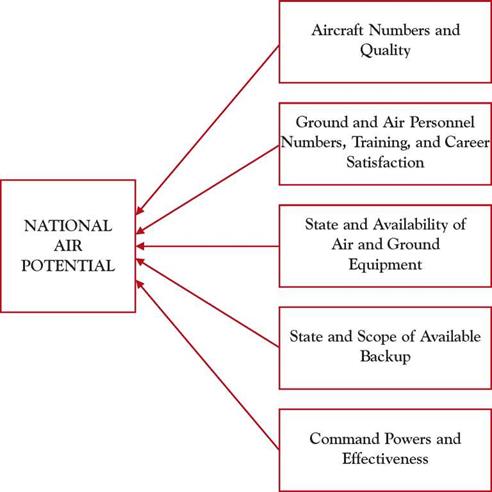

National air potential is the basis of air power. Air potential is the state and ability of the components of air power, or the state and ability of forces and material directly involved in task performance. It is not necessary to tap the full measure of national air potential at all times. The precise extent depends on many factors, chief among them the nature of tasks.

One may regard air potential as succour for the air power system, and as a system of several elements (Diagram 4) grouped according to the possibility of actualisation of air power components and elements. They may be regarded as an entry point into the system of air potential, whose final product is the degree of its actualisation.

The elements of air potential include:

– aircraft number and quality

– ground and air personnel numbers, training and career satisfaction

– air and ground equipment state and availability

– state and scope of available backup

– command structure powers and effectiveness.

Air power is the extent to which air potential becomes reality. The assessment of this extent is of necessity subjective. It depends on the extent of actualisation of

various elements of air potential. There are cases where for one reason or another components of air power, or elements of air potential, are missing or undeveloped. This does not mean that air power is absent, or that it cannot rise beyond a certain level. However, it does mean that the ultimate degree of air power is circumscribed.

Apart from depending on objective conditions, the extent of available air power may also be fixed by politicians and soldiers with a view to adequacy in the pursuit of set objectives.

The proposed view of air power makes it obvious that it is an element of national power able to discharge duties both in peace and in wartime. One may glean a fuller picture of its multifarious peacetime duties from this list:

|

Diagram 4: The Components of air potential 21 |

– deterring potential aggression

– assisting in disasters or crisis situations

– assisting national business, science and research

– patrolling and controlling national airspace

– maintaining combat readiness and preparedness for a smooth transition from peace to war.

Manifestations of the business role of air power include:

– state and private sector airlines

– R&D establishments and firms with interests in aviation

– the air design and manufacturing sector which bridges the gap between fundamental research and manufacturing

– the aviation community (those who earn a living in aviation and related interests).

The airforce as a component of air power plays a special role in peacetime. As part

of the armed forces, it is able to display national armed power on the international arena. Politicians often make use of this to demonstrate a threat to adversaries. German politicians pioneered this use of air power. A similar display arsenal for the use of diplomacy was widely used during the Cold War and remains deployed today. Demonstrations of aerial might often allow the attainment of political objectives without recourse to combat: the mere threat of potential superiority or mastery supplants spilt blood.

In this sense air power has always been an instrument of national policy and a major buttress to peacetime diplomacy. This is helped by the nature of the airforce: constantly combat ready, mobile, and able to concentrate forces rapidly with great accuracy. The ability to influence adversaries simply because the airforce is there bring the creation of air power to the forefront as a priority national issue, and to the forefront in international politics. Here, Bulgaria’s lack of an adequate level of air potential, and the process of downgrading air potential (in progress as these words are written) erode Bulgarian leaders’ positions on the international arena.

At the same time air power, along with the other elements of national power, is there to defend the nation in case of attack. Thus, its importance for national safety grows in line with military threat. Primary expression of this aspect of air power is a country’s ability to repel aggression. However, this does not mean that air power ends with the airforce. One must interpret air power primarily as a nation’s ability to harness all resources and opportunities at its disposal to the end of utilising airspace. The basic aim here is to boost national prosperity, with defence as part of this aim.

Regarded thus, air power may to some definite extent be seen as synonymous with national economic prowess, whose inalienable constituent it indeed is. It is economic power that determines the level of armed power (hence also of air power); air power has both commercial and military origins.

The reason people invest air power with military meanings is mostly to do with international factors. Threat, and the concomitant need for defence, are immanent in international relations. In this sense, tasks before air power in a conflict include:

– controlling national airspace

– controlling enemy airspace

– continuous aerial reconnaissance and intelligence gathering using the advantages of the third dimension

– transport operations.

The relative importance of army, airforce, and navy, has always depended on political and strategic considerations, geography, and international alliances. The army has played first fiddle in some historical periods; in others, primacy has rested with the airforce or navy. The place and role of each armed force in peace and war depends on the technical level of adversaries, their potential, and their geography.

Experience shows that each of the forces makes a definite and always significant contribution to victory. Over the last century (since the arrival of air power) there have been no pure infantry, naval or air wars; neither do military experts foresee any in future. One thing remains unaltered: only the army can secure the results of a campaign or a war. Its sheer physical presence on the ground consolidates the conquests of hot conflict.

Conditions for the attainment of set objectives arise only where organised, wellarmed, and well-trained armed forces are available. Each of them has a specific sphere of application, and modes of interplay with the others. The appropriate utilisation of this specificity determines the degree of success of an operation, campaign, or war. Precisely because of this, the pursuit of balance between the different armed forces (and within each of them) is a major procedure in modern military science. National interests guide this procedure closely as do, inter alia, tasks set by political and military leaders, political and military developments in the region and beyond, national potential, and geography. The procedure is also the key to a broader challenge: striking a balance between the components of air power.

In constructing air power, attention must be paid to blend its components most advantageously, and to maintain this blend thereafter. This is only possible after thorough scientific analysis of all influences on civil and military aviation. Balancing thus involves military science and addresses historical and technical developments. The issue of balancing also intrigues per se, inviting examination in an historical and military science aspect.

Military doctrine and national security postulates, as well as the national constitution, have to form the basis of balanced development of air power. They must determine the role and place of air power and the airforce within the hierarchy of national power, and national armed power. They must fix its relative weight in the system, its

tasks in peace and war, and the composition and purpose of various force commands and civic volunteer formations.

A conclusion valid for nations with Bulgaria’s economic potential, is that balancing the components of air power means bringing them to a state and blend which allows air power to be multi-role (able to perform a variety of peace and wartime tasks).

In view of the basic requirements before air power (to perform set tasks using its peacetime strength while taking account of geography, and to manoeuvre using available resources), another major procedure is to determine human and material strength. Here, it must be borne in mind that force renewal in today’s swift wars is highly problematic, and generally considered impossible. Thus, the issue of balancing and creating air power is mainly a matter of peacetime planning.

Balancing the components of air power is an ongoing process. It evolves according to historical circumstances. Major factors determining such evolution include: politics (changing balances, military blocs, and changes of regime); economic realities and changes in national commercial/military potential; developments in indigenous and world science; and changes in the tasks before air power. Tasks set by political leaders and the level of national economic development are prime among these factors.

History is replete with examples of defeat or distress resulting from poor (or nonexistent) balance among elements of national power and components of air power. Most of these relate to financial straits, mistaken military doctrines, or short-sighted foreign policies. The national economy then has to make up for such defeat and distress.