Fundamental to understanding how decisions were made with respect to space is thus the approach Richard Nixon took to assembling his senior White House staff. First in significance and power among Nixon’s immediate associates was Harry Robbins “Bob” Haldeman, whom soon after the election Nixon designated as the White House chief of staff. Haldeman’s background was in advertising; he had worked for the giant advertising company J. Walter Thompson for 20 years, taking time off during Nixon’s 1960 presidential and 1962 gubernatorial campaigns. Haldeman and his staff controlled all papers flowing into and out of the Oval Office and controlled access to the president for all but a very few individuals who had “walk-in rights.”28

Haldeman presented himself as being overridingly concerned with the process of making policy choices rather than their substance; he was dedicated to making sure that Nixon received all plausible policy options before reaching a decision. There was one important fact that Haldeman kept secret from Nixon—that he was compiling a detailed day-by-day account of the Nixon White House. He marked the daily entries “Top Secret” and stored them in a White House safe. Twenty years after leaving the White House under the cloud of the Watergate scandal, Haldeman, believing that his diary would “provide valuable insights for historians, journalists, and scholars,” decided to make it public. A book containing some 40 percent of the 750,000 words in the diaries was published in 1994, after Haldeman’s death.29

Although at the outset of the Nixon administration John Ehrlichman had a secondary role among the president’s advisors, during 1969 he quickly became together with Haldeman a powerful member of Richard Nixon’s inner circle. Ehrlichman was Bob Haldeman’s college classmate, then got a law degree, and began a successful practice in Seattle. He, like Haldeman, was a veteran of Nixon’s prior political campaigns. At the start of the Nixon administration, both Haldeman and Ehrlichman “were almost wholly ignorant of major national issues, the federal government, and politics in its broadest sense. . . That positions of such power and influence should be filled by men of such slight experience in public affairs” was described as “the single most extraordinary aspect of the early Nixon White House.”30

Of Nixon’s innermost circle, it was Ehrlichman who over the next few years would get most involved in space-related issues.

Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and other senior Nixon advisers acquired sizeable staffs to assist them in their responsibilities. Many of these staff members were under 30 years in age—much more so than in previous White House staffs. They were chosen primarily for their “pugnacity and proven loyalty,” and were equally as inexperienced in actually managing the federal government as were Haldeman and Ehrlichman. During 1969 and 1970, a young staff assistant several layers down in the White House hierarchy, Clay Thomas “Tom” Whitehead, would have a great deal of influence in shaping decisions on post-Apollo space activities.

A third member of Nixon’s inner circle was his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. His choice was somewhat surprising; Kissinger as a Harvard professor had long been a protege of New York governor and potential rival for the 1968 Republican presidential nominee Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon did not know Kissinger well before his election, but soon afterward the two met and found they thought along very similar lines with respect to international issues. Kissinger was quickly offered the national security advisor position and after consulting Rockefeller and others in the East Coast Republican establishment accepted Nixon’s invitation to join his administration.

The relationship between Nixon and his three senior advisers was strictly professional. Leonard Garment, one of Nixon’s law partners during the 1960s who came to Washington with Nixon in January 1969 and served in the White House through almost all of the Nixon administration, suggests that “the relationships among Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Kissinger, and Nixon were singularly devoted to the breeding and tending of power. They were not friends, not even a little. Indeed, if the members of Nixon’s German general staff shared an emotion, it was an intense dislike of Nixon, which he returned.” Garment notes that this “strange quartet” after 1969 was

|

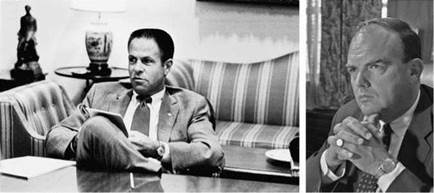

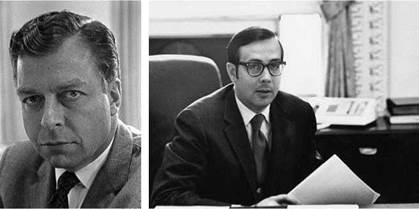

H. R. “Bob” Haldeman (left) and John Ehrlichman (right), President Richard Nixon’s top advisers on domestic policy and politics. (Photographs WHPO 6106-6 and WHPO 1040-22A, courtesy of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library & Museum)

|

increasingly able to centralize control over executive branch activities until the forces of Watergate scandal tore them apart.31

There was an important shift in the context within which the civilian space program was viewed by the Nixon administration compared to the approach since 1957; that earlier approach had seen space as primarily a foreign policy and national security issue. The primary rationale for the kind of space program that the United States had pursued during the 1960s was as a peaceful symbol of national power and as a foreign policy tool in the Cold War U. S.-Soviet competition. While Nixon recognized the continuing foreign policy salience of space achievements, by the time he entered the White House he had concluded that more domestically oriented rationales for what the United States would do in space after Apollo, such as applying space capabilities to problems on Earth and seeing the space program as a stimulus to technological innovation and as a way of maintaining a qualified aerospace industrial and employment base, would have priority in shaping his space policy. The race to the Moon was on the verge of being won, and Nixon saw no compelling reason to continue the space program at a racing pace. By treating space as primarily a domestic rather than a national security and foreign policy issue, the Nixon administration changed the calculus by which the benefits of a post-Apollo space effort would be measured. It was thus individuals on the Nixon White House staff with responsibility for domestic policy issues who had particular influence on Richard Nixon’s space policy choices. This choice also meant that Nixon himself, who was far more interested in foreign policy than domestic issues, would view space policy as a matter of secondary concern.

The senior member of Nixon’s staff with direct oversight responsibility with respect to NASA was thus Assistant to the President Peter Flanigan. Flanigan’s other policy responsibilities were issues related to the U. S. financial community and international trade, to the 15 independent regulatory agencies that were then part of the executive branch, and to other technical government agencies like the National Science Foundation and the Atomic Energy Commission. At the outset of the Nixon administration, this position had been filled by former Congressman Robert Ellsworth. But Ellsworth had hoped for a more responsible position, and soon was ready to leave the White House to become ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. He was replaced in April 1969 by Flanigan, described by Ehrlichman as a “young prince of Wall Street.”32 Flanigan was an investment banker and also a veteran of Nixon campaigns in 1960 and 1962. He had served the Nixon 1968 presidential campaign as its link to the financial community. As he assumed his White House position in April, Flanigan inherited from Ellsworth’s staff the previously mentioned Tom Whitehead as one of his staff; Whitehead was Flanigan’s primary assistant for NASA issues. Whitehead held a doctorate in management from MIT, where he had first majored in engineering. He during the 1960s had spent time at the Rand Corporation, a think-tank steeped in a systems analysis approach to assessing policy issues. Flanigan and Whitehead were to play key policy roles

|

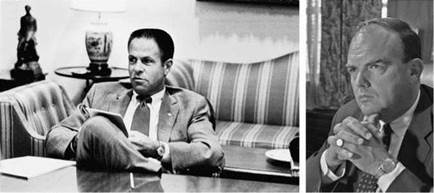

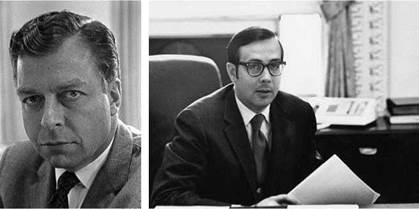

Nixon assistants Peter Flanigan (left) and Clay Thomas Whitehead (right). (Photographs WHPO 1092-21 and MUG-W-322, courtesy of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library & Museum)

|

in shaping the approach that the Nixon administration would take to the post-Apollo space program.

At the center of this small group of individuals sat Richard Nixon, “a loner, seated in an Oval Office as hushed and solemn as a hermitage.” Nixon designed his approach to governance to isolate himself “from the demands of the hated bureaucracy while ensuring that power was centralized in the White House.” Much of Nixon’s communication with his immediate staff was through notes he scribbled on the memorandums and on daily news summaries he read in the evenings as he sat alone. Nixon was an “improbable president” who “didn’t particularly like people. . . lacked charm or humor or joy,” and was “virtually incapable of small talk.” Nixon was “insecure, self-pitying, vindictive, suspicious. . . and filled with long-nursed anger and resentments.” This study will not probe deeply into the Nixon psyche. There are many other accounts of this “peculiar man” that analyze the way his personality influenced his conduct as president; on occasion, however, it will be clear how some of his peculiarities affected his space decisions.33

Because Nixon and his advisers were unfamiliar with how the process of governing actually worked and suspicious of career government bureaucrats, they seem to have underestimated the importance of the “institutional presidency” lodged in the Executive Office of the President. With respect to space issues, the Bureau of the Budget (BOB) and the Office of Science and Technology (OST) were particularly important. While the president could appoint the heads of these offices, the staffs of both were career government employees, more dedicated to supporting the institution of the presidency than to supporting any particular president. In order to make sure that these offices served the priorities of a particular president, in this case Richard Nixon, the individuals he appointed to lead these offices had to be strong managers, able to transmit the president’s policy priorities to the permanent staff and able to see that they were reflected in specific recommendations and decisions. This did not happen at the start of the Nixon administration. Nixon selected as director of BOB a Chicago banker named Robert Mayo, whom he did not know. Mayo was suggested by Nixon’s nominee for secretary of the treasury, David Kennedy, another Chicago banker, for whom Mayo had worked. Mayo turned out to an individual with whom Nixon found it unpleasant to deal; he was a weak BOB director and would leave the administration in 1970. Nixon selected as his science advisor and director of OST Lee DuBridge, the retiring president of the prestigious California Institute of Technology. Nixon had known DuBridge for over 20 years, but he also soon discovered that DuBridge was neither a strong leader nor someone to whom Nixon could turn for advice reflecting the president’s interests. By the end of 1969 DuBridge found himself increasingly marginalized in the policy process, and he too would leave the White House in 1970. But it was DuBridge and his OST staff and Mayo and his BOB staff who would join with Peter Flanigan and Tom Whitehead to deal with space issues on a continuing basis during 1969.