Home in orbit

LIFT-OFF

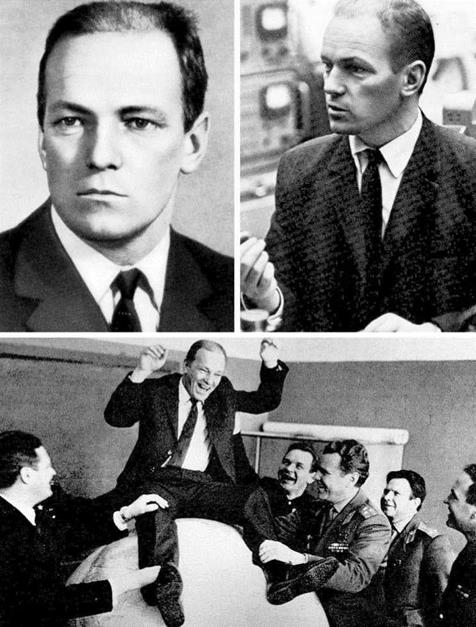

When Georgiy Dobrovolskiy, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev were woken up at 3 a. m. on Sunday, 6 June 1971, it was still dark at the Baykonur cosmodrome. They briefly exercised, shaved, had a light breakfast – their last meal on Earth – and then the final medical checks. An hour later, after brief reports of the status of the rocket and Soyuz 11 spacecraft, the State Commission gave the ‘green light’ for the launch, and the rocket was fuelled. In contrast to previous missions, this time there were no backups to ride with the crew to the pad. However, they were accompanied on the bus by the Soyuz 10 cosmonauts and some of the officials from the TsKBEM and the TsPK. Just before 5 a. m., with dawn breaking, the bus drew up to the pad, where members of the State Commission, designers, engineers, technicians, military officers, pad workers, TV crews and reporters were waiting.

The cosmonauts wore grey cotton flight suits. Traditionally, military cosmonauts wore officers’ caps, but this time all three men wore pilot caps with a badge on the front depicting the Soviet coat of arms. In addition, each man had on his left arm a tall triangular patch with a dark-blue background, a yellow rocket rising from the Earth towards yellow stars, and the letters ‘CCCP’ below. In contrast to American astronauts, the majority of Soviet cosmonauts did not wear ‘mission patches’. The first Soviet patch was designed for Valentina Teryeshkova in 1963, and it was sewn on the blue garment that she wore inside her bright orange pressure suit; it depicted a dove and a small laurel branch. The second patch was created by Aleksey Leonov, a passionate space artist, and was worn on the right arm of his space suit during his historic spacewalk in 1965. Khrunov and Yeliseyev both wore Leonov’s patch for their external transfer from Soyuz 5 to Soyuz 4, because they wished to retain it as a symbol of spacewalking. The early cosmonauts had ‘CCCP’ in large red letters on their white helmets, but their successors in cotton suits did not have a patch, a coat of arms or even a flag. But in mid-1970, training for the DOS missions, Leonov put his old patch on his flight suit. Kolodin did likewise, but Kubasov seems not to have

joined in.1 As their backups, Dobrovolskiy, Volkov and Patsayev also accepted it. In addition, Volkov had a small rectangular white badge on the left side of his chest.

After Dobrovolskiy had made a brief report to General Kerimov, the chairman of the State Commission, the cosmonauts, surrounded by journalists and pad workers, walked to the rocket, which was lit by floodlights. This was another contrast to the NASA way, whose astronauts don their suits in a building 8 km from the pad and, upon emerging, simply wave to friends and reporters on their way to the van which drives them to the pad, which is clear apart from the team whose task is to assist the crew into the spacecraft. At Baykonur, the departing crew walks through the crowd, speaking to individuals, even joking. Dobrovolskiy, Volkov and Patsayev halted in front of the stairs to the elevator, turned and waved. Reading from a piece of paper, Dobrovolskiy began a speech: “I bow my head to all of you for your attentiveness, for your effort.” Then as they smiled to the numerous TV and photographic cameras, Volkov whispered to Dobrovolskiy: “It’s time to go.”

Volkov led the way up the steps, with Patsayev and Dobrovolskiy following. The liquid oxygen boiling off from the rocket blew in small clouds past the cosmonauts. At the top of the steps, Dobrovolskiy turned and called to the crowd: “Don’t worry. Everything will be normal; everything will be normal!’’ The three men paused at the door of the elevator to wave. Even Patsayev smiled. Then they disappeared into the elevator. When they emerged on the platform leading to the hatch in the side of the orbital module of their spacecraft, they posed for one of the photographers, which is another notable detail of this mission because cosmonauts did not generally pose on this platform. The result was one of the most extraordinary photographs taken of this crew. As a final farewell, the three men stood at the railing of the platform and waved their caps at the crowd.

Technicians assisted first Volkov, then Patsayev and finally Dobrovolskiy to enter the spacecraft. Access was through the side hatch of the orbital module, then down through the interior hatch into the descent module, which contained their couches.[56] [57] When Volkov had taken his place, he switched on the cabin lights and ventilators. Once Patsayev was in place, Dobrovolskiy joined them. The technicians bid them farewell and hermetically closed the hatch between the descent and orbital modules, then the external hatch of the orbital module. With the cabin sealed, the silence was striking. Each cosmonaut donned a cap of white net which included earphones and a small microphone on each side. There was still an hour remaining to the time of launch.

As they settled in, Volkov turned to Dobrovolskiy, they smiled at each other, and Volkov pointed towards Patsayev, who was quietly gazing out of the small porthole by his left shoulder. Finally, Patsayev turned his head inwards to his colleagues, and smiled.

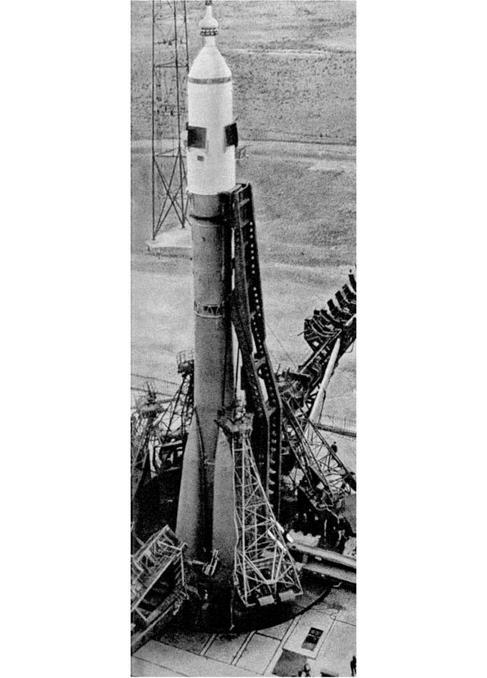

With 30 minutes to go, the twin sections of the service structure split the eight levels of the wrap-around walkway and swung down to leave the rocket exposed on

|

After a final wave from the top of the service structure, with the nozzles of the solid motors of their vehicle’s launch escape system in the background, the Soyuz 11 crew pose for a photograph moments before boarding their spacecraft. |

the pad. Ten minutes later, the topping-off of the liquid oxygen tanks ceased and the kerosene tanks were pressurised.

The control room was in a bunker some 2 km from the pad. A black-and-white TV monitor showed the cabin, but because the camera was located above Volkov’s head only Dobrovolskiy and Patsayev were visible. The communication officer was Leonov. Also present was Afanasyev of the Ministry of General Machine Building, who had just arrived from Moscow. The traditional radio call-sign for the TsUP was Zarya.[58] The call-sign for the mission was Yantar.[59]

At 7.40 a. m., Dobrovolskiy reported: “This is Yantar, and we’re ready to go up.’’

With just 40 seconds remaining, the rocket was switched to internal power and its automatic sequencer was activated. Twenty seconds later, the umbilical arm swung away.

The cosmonauts could hear the final commands. They tightened their seatbelts. The fuel tower withdrew from the vehicle.

Volkov, the only veteran, who knew the launch commands very well, again joked: “Let us wave farewell to them.” They waved to the TV camera. Then: “The key is on the Start button.”

A second later, the launch operator repeated this command. Dobrovolskiy turned to Volkov: “It looks like you want to go early.”

The final commands:

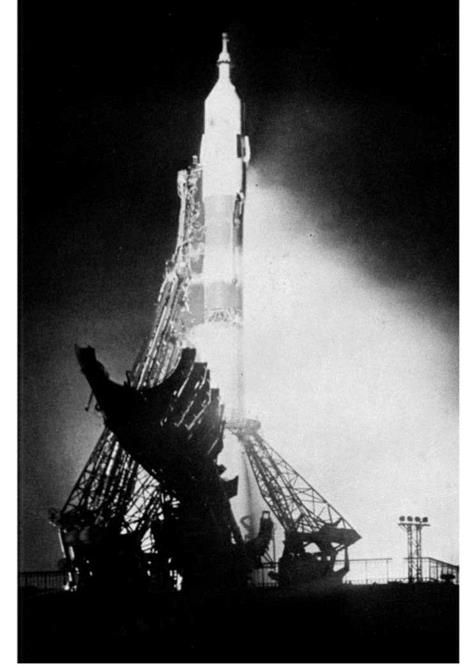

“Ignition!”

“The main!”

“Start!”

The vehicle had a central core stage and four strap-on boosters, each with a main engine. A turbopump in each of the five segments began to feed fuel and oxidiser. At 7.55 a. m., pyrotechnic charges were simultaneously fired to start the five main engines. The rocket was not actually supported at its base; the core was held by four arms located just above the top of the strap-ons. As soon as the thrust overcame its 310-tonne mass, the rocket began to lift. This released the supporting arms, which immediately swung out like the petals of a flower in order to clear the way for the protruding strap-ons. One way or another, Dobrovolskiy, Volkov and Patsayev were now committed.

The launch was perfect.

Dobrovolskiy reported that there was very little vibration.

After initially rising vertically, the rocket pitched over to a northeasterly heading, and as it ascended through the atmosphere it passed almost directly over the town of Baykonur, some 350 km from the launch site.[60] At 115 seconds, at an altitude of about 45 km, the ring of solid-rockets at the top of the 6-metre-tall escape tower were fired to pull it free of the vehicle. A few seconds later, the four 20-metre-long strap – ons shut down and were jettisoned. The core continued and, with half of its propellant used, it accelerated rapidly. At an altitude of 80 km, above most of the atmosphere, the shroud which had protected the spacecraft from aerodynamic loads was jettisoned. At 288 seconds, at an altitude of 175 km, the 30-metre-long core shut down and was jettisoned. The four-chambered engine of the 8-metre-long third stage started immediately, and by the time that it had built up to its full 35-tonne thrust the framework interstage had been jettisoned too. Soon the third stage began to pitch over further in order to increase its horizontal speed.

At 8.02 a. m., the report from the spacecraft was: “Temperature is 22°C, pressure is 840 millibars, all is well.”

At 8.04 a. m., far north of China, the third stage shut down. Dobrovolskiy reported: “Orbital insertion. Commencing separation, stabilisation. Antennae and solar wings deployed. On board everything is in order. Feeling normal.”

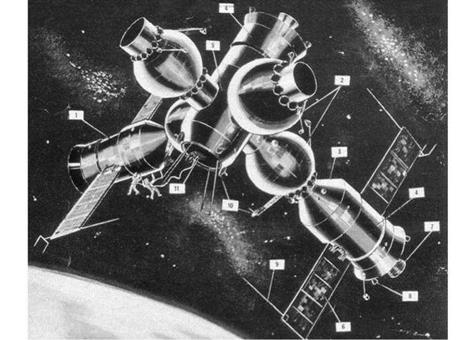

The parameters of the initial orbital were: altitude 185 x 217 km at 51.6 degrees to the equator and a period of 88.3 minutes. At the time, Salyut’s orbit was 212 x 250 km in the same plane with a period of 88.8 minutes.

|

Soyuz 11 on the pad, minutes before ignition. |

|

4 ^ |

The first Western site to detect signals from the new spacecraft was the Kettering Grammar School in Northamptonshire, England, which picked up a signal within 10 minutes of launch. Geoffrey Perry, the senior science master who led the tracking team, was able to announce the launch of a spacecraft carrying three men more than an hour ahead of the Moscow news report. In fact, because the Kettering team had noticed that after a period of silence lasting almost five weeks Salyut had recently made several manoeuvres and started to transmit signals, they had been awaiting the launch.[61]