n 1913, the state of aeronautical advance in the United States was primarily represented by the accomplishments of Glenn Curtiss. Conversely, leaders in Europe had invested heavily in aircraft technology. Competitions were regularly sponsored to encourage advances in aircraft speed, range, and altitude. Europeans had also incorporated aircraft units in their armed forces prior to the first world war. In 1913, the United States had only six pilots in the entire U. S. Army.

In July 1914, the conflict that was to become known as “The Great War” or World War I opened with the Austro-Hungarian invasion of Serbia, which was soon followed by a German invasion of the low countries of Western Europe, Belgium, and Luxembourg, as well as France. Russia attacked Germany. The combatants aligned into the Allied Powers, consisting mainly of Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Japan, and the United States, and the Central Powers, mainly Germany, Austro-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria. The conflict ended on November 11, 1918.

As in most wars, technological advances in weapons and support were greatly accelerated between 1914 and 1918. The United States was late entering the conflict (1917) and did not participate in the major aircraft innovations that occurred

during the war. European manufacturers and designers had jumped ahead in aircraft and engine design, partly out of necessity. On the Allied side, the French Nieuport, followed by the SPAD, manufactured by the French company Societe des Productions Armand Deperdussin (hence the acronym), and the English S. E. 5, Sopwith Pup, and Sopwith Camel, provided the fighter aircraft. In 1918, close to the end of World War I, Glenn Martin was responsible for contributing the only American design for combatant aircraft in the war with his MB-1 bomber. On the Central Powers side, the German manufacturers Junkers and Albatros Werke GmbH produced formidable fighter aircraft, but the Fokker designs proved to be the best, particularly the D. VII, which is widely regarded as the best fighter of the war. This aircraft was flown by Hermann Goering, who was to become the second-in-command to Adolf Hitler in the 1920s and the leader of the German Luftwaffe in the 1930s and during World War II.

Although the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company was the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world during the war, producing 10,000 planes by 1918, the JN-4 did not come close to matching European models in speed, power, ceiling, and reliability. First produced in 1916, the

Jenny mounted the OX-5 engine, 90 horsepower and water-cooled. When Curtiss improved his О model engine in 1913, he wanted to publicize its advances by designating it the “O Plus.” But neither the “O Plus” nor the “0+” designation looked particularly good when printed, and the “+” could even be confused with the letter “T.” Someone suggested rotating the Plus sign by 45 degrees, depicted as “OX,” and the new series of engines became known as the OX-2.

The Curtiss models, although behind the Europeans, were higher performance machines than those built by the Wrights. The Wright Company had fallen by the wayside in aircraft design by World War I, its designs being almost entirely based on the outmoded Flyer models.

Manufacturing in the United States upon its entry into the war was made subject to the oversight and control of the Aircraft Production Board, the creation of which was a recommendation of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (see below) which decreed that the United States should gear up to produce 22,000 aircraft for delivery to France within a year. Isolated between two great oceans, America was far removed from the vast destruction war had brought to Europe just since 1914, and the world was about to appreciate how valuable the heavy manufacturing reserve of the United States could be. But America was too far behind the design performance standards of aircraft already in use in Europe, so much of the American production effort was limited to manufacturing aircraft under license from European designers.

The De Havilland DH-4, a single-engine bomber/observation plane, was the primary military airplane built in the United States during the war. The Dayton-Wright Company built the most, 3,106 planes, followed by Fisher Body at 1,600, and Boeing, which produced 150.

The Wright Company concentrated on the production of engines under license, notably the 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza aircraft engine, much in demand by the French. Hispano-Suiza was a Spanish engine and automobile company that, in 1915, refined its V8 liquid-cooled automobile engine for aeronautical use. This engine represented a quantum advance over the rotary engine, which at the time was the primary aircraft engine in use. The French government in 1915 placed orders in the United States for 800 engines, which were required to be built in the United States due to the lack of capacity in Europe during the war. The Wright Company contracted to supply 450 of these. To facilitate filling the order, the Wright Company arranged a merger with Glenn L. Martin in 1916 to form the Wright-Martin Aircraft Company. By the end of the war, the company had produced over 10,000 of the engines, known as the Wright-Hispano. Along the way, the Wright-Hispano replaced the 90-horsepower Curtiss OX-5 in the Curtiss Jenny, which was limited to training use. After the war, in 1919, the Wright-Martin combination was dissolved and the company became the Wright Aeronautical Corporation. Much was to be heard from this company for its contributions to aircraft engine development during the 1920s.

With the entry of the United States into the war, the Aircraft Production Board ordered the production of 44,000 American-built aircraft engines to be used in conjunction with the ambitious goal of manufacturing over 22,000 aircraft. The immediate problem was, however, that the United States did not possess an aircraft engine capable of providing sufficient horsepower or speed for military airplanes. Packard Motors happened to have in its design inventory an experimental, but tested, 8-cylinder liquid-cooled automobile engine that was to prove the basis for America’s greatest contribution to the war effort. On May 29, 1917, automobile engineers at Packard began a redesign of the engine with the purpose of supplying the ordered military aircraft engine, and five days later, a revised design was presented for aircraft use. But it was still an automobile engine, having battery ignition instead of magnetos, for example. It was redesigned again, this time expanding its power to 12 cylinders like the British Rolls engine, and with magneto ignition. The new design, the water-cooled Liberty, weighed only 710 pounds and, producing 410 horsepower, it surpassed the performance of all other aircraft engines in the world. By war’s end, some 17,935 Libertys had been produced, of which 5,827 had been delivered to Europe for use in aircraft there. The Liberty was installed in the DH-4, and by November 1918 deliveries to the Army numbered 3,431 airplanes. Of these, 1,213 arrived in Europe, but only 248 ever flew at the front.

When the Armistice was signed, so many airplanes and engines had been produced for war use that engine and airplane manufacturing literally stopped cold. Surplus equipment was everywhere, and it was cheap. Curtiss Jennys were so numerous that, for $500, a student pilot could receive his instruction and upon solo be awarded a Jenny in the bargain.

As peace settled once again over the world, as the railroads were returned to their owners by the government, as the automobile began hitting the open roads being built by the government, and as all of the planes appeared to be sitting on the ground, many wondered what would become of aviation in America.

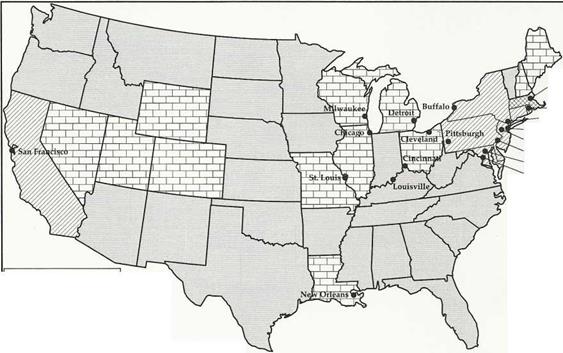

The pendulum had swung too far in the early and energetic days of railroading, and the government was now catching up to balance things out in the public interest. The days of unbridled capitalism in the railroad business were over. In the early years of the 20th century, the railroads were nearing what was to be their maximum trackage (miles of laid tracks), and they were just about to experience the effects of continuing industrial and technological development (Figure 3-4 displays the emergence of U. S. cities in 1880) that would lead to alternative forms of transportation that would overpower them. The days of the internal combustion engine, the open road, and the machines of the air lay just over the horizon.

The pendulum had swung too far in the early and energetic days of railroading, and the government was now catching up to balance things out in the public interest. The days of unbridled capitalism in the railroad business were over. In the early years of the 20th century, the railroads were nearing what was to be their maximum trackage (miles of laid tracks), and they were just about to experience the effects of continuing industrial and technological development (Figure 3-4 displays the emergence of U. S. cities in 1880) that would lead to alternative forms of transportation that would overpower them. The days of the internal combustion engine, the open road, and the machines of the air lay just over the horizon.