Its thermal environment during re-entry was less severe than that of an ICBM nose cone, allowing designers to avoid not only active structural cooling but ablative thermal protection as well. This meant that it could be reusable; it did not have to change out its thermal protection after every flight. Even so, its environment imposed temperatures and heat loads that pervaded the choice of engineering solutions throughout the vehicle.

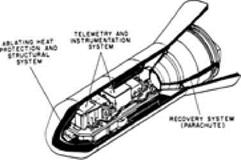

Dyna-Soar used radiatively-cooled hot structure, with the primary or load-bearing structure being of Rene 41. Trusses formed the primary structure of the wings and fuselage, with many of their beams meeting at joints that were pinned rather than welded. Thermal gradients, imposing differential expansion on separate beams, caused these members to rotate at the pins. This accommodated the gradients without imposing thermal stress.

Rene 41 was selected as a commercially available superalloy that had the best available combination of oxidation resistance and high-temperature strength. Its yield strength, 130,000 psi at room temperature, fell off only slightly at 1,200°F and retained useful values at 1,800°F. It could be processed as sheet, strip, wire, tubes, and forgings. Used as the primary structure of Dyna-Soar, it supported a design specification that indeed called for reusability. The craft was to withstand at least four re-entries under the most severe conditions permitted.

As an alloy, Rene 41 had a standard composition of 19 percent chromium, 11 percent cobalt, 10 percent molybdenum, 3 percent titanium, and 1.5 percent alu

minum, along with 0.09 percent carbon and 0.006 percent boron, with the balance being nickel. It gained strength through age hardening, with the titanium and aluminum precipitating within the nickel as an intermetallic compound. Age-hardening weldments initially showed susceptibility to cracking, which occurred in parts that had been strained through welding or cold working. A new heat-treatment process permitted full aging without cracking, with the fabricated assemblies showing no significant tendency to develop cracks.24

As a structural material, the relatively mature state of Rene 41 reflected the fact that it had already seen use in jet engines. It nevertheless lacked the temperature resistance necessary for use in the metallic shingles or panels that were to form the outer skin of the vehicle, reradiating the heat while withstanding temperatures as high as 3,000°F. Here there was far less existing art, and investigators at Boeing had to find their way through a somewhat roundabout path.

Four refractory or temperature-resistant metals initially stood out: tantalum, tungsten, molybdenum, and columbium. Tantalum was too heavy, and tungsten was not available commercially as sheet. Columbium also appeared to be ruled out for it required an antioxidation coating, but vendors were unable to coat it without rendering it brittle. Molybdenum alloys also faced embrittlement due to recrystallization produced by a prolonged soak at high temperature in the course of coating formation. A promising alloy, Mo-0.5Ti, overcame this difficulty through addition of 0.07 percent zirconium. The alloy that resulted, Mo-0.5Ti-0.07Zr, was called TZM. For a time it appeared as a highly promising candidate for all the other panels.25

Wing design also promoted its use, for the craft mounted a delta wing with a leading-edge sweep of 73 degrees. Though built for hypersonic re-entry from orbit, it resembled the supersonic delta wings of contemporary aircraft such as the B-58 bomber. However, this wing was designed using the Eggers-Allen blunt-body principle, with the leading edge being curved or blunted to reduce the rate of heating. The wing sweep then reduced equilibrium temperatures along the leading edge to levels compatible with the use ofTZM.26

Boeings metallurgists nevertheless held an ongoing interest in columbium because in uncoated form it showed superior ease of fabrication and lack of brittleness. A new Boeing-developed coating method eliminated embrittlement, putting columbium back in the running. A survey of its alloys showed that they all lacked the hot strength ofTZM. Columbium nevertheless retained its attractiveness because it promised less weight. Based on coatability, oxidation resistance, and thermal emis – sivity, the preferred alloy was Cb-10Ti-5Zr, called D-36. It replaced TZM in many areas of the vehicle but proved to lack strength against creep at the highest temperatures. Moreover, coated TZM gave more of a margin against oxidation than coated D-36, again at the most extreme temperatures. D-36 indeed was chosen to cover most of the vehicle, including the flat underside of the wing. But TZM retained its advantage for such hot areas as the wing leading edges.27

The vehicle had some 140 running feet of leading edges and 140 square feet of associated area. This included leading edges of the vertical fins and elevons as well as of the wings. In general, D-36 served where temperatures during re-entry did not exceed 2,700°F, while TZM was used for temperatures between 2,700 and 3,000°F. In accordance with the Stefan-Boltzmann law, all surfaces radiated heat at a rate proportional to the fourth power of the temperature. Hence for equal emissivities, a surface at 3,000°F radiated 43 percent more heat than one at 2,700°F.28

Panels of both TZM and D-36 demanded antioxidation coatings. These coatings were formed directly on the surfaces as metallic silicides (silicon compounds), using a two-step process that employed iodine as a chemical intermediary. Boeing introduced a fluidized-bed method for application of the coatings that cut the time for preparation while enhancing uniformity and reliability. In addition, a thin layer of silicon carbide, applied to the surface, gave the vehicle its distinctive black color. It enhanced the emissivity, lowering temperatures by as much as 200°F.

Development testing featured use of an oxyacetylene torch, operated with excess oxygen, which heated small samples of coated refractory sheet to temperatures as high as 3,000°F, measured by optical pyrometer. Test durations ran as long as four hours, with a published review noting that failures of specimens “were easily detected by visual observation as soon as they occurred.” This work showed that although TZM had better oxidation resistance than D-36, both coated alloys could resist oxidation for more than two hours at 3,000°F. This exceeded design requirements. Similar tests applied stress to hot samples by hanging weights from them, thereby demonstrating their ability to withstand stress of 3,100 psi, again at 3,000°F.29

Other tests showed that complete panels could withstand aerodynamic flutter. This issue was important; a report of the Aerospace Vehicles Panel of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board (SAB)—a panel on panels, as it were—came out in April 1962 and singled out the problem of flutter, citing it as one that called for critical attention. The test program used two NASA wind tunnels: the 4 by 4-foot Unitary facility at Langley that covered a range of Mach 1.6 to 2.8 and the 11 by 11-foot Unitary installation at Ames for Mach 1.2 to 1.4. Heaters warmed test samples to 840°F as investigators started with steel panels and progressed to versions fabricated from Rene nickel alloy.

“Flutter testing in wind tunnels is inherently dangerous,” a Boeing review declared. “To carry the test to the actual flutter point is to risk destruction of the test specimen. Under such circumstances, the safety of the wind tunnel itself is jeopardized.” Panels under test were as large as 24 by 45 inches; actual flutter could easily have brought failure through fatigue, with parts of a specimen being blown through the tunnel at supersonic speed. The work therefore proceeded by starting at modest dynamic pressures, 400 and 500 pounds per square foot, and advancing over 18 months to levels that exceeded the design requirement of close to 1,400 pounds per square foot. The Boeing report concluded that the success of this test program, which ran through mid-1962, “indicates that an adequate panel flutter capability has been achieved.”30

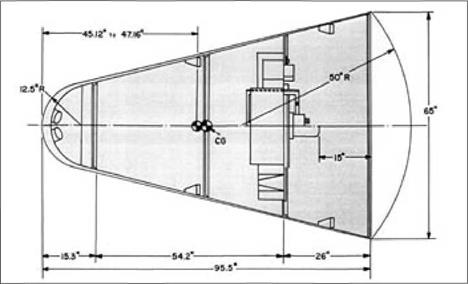

Between the outer panels and the inner primary structure, a corrugated skin of Rene 41 served as a substructure. On the upper wing surface and upper fuselage, where temperatures were no higher than 2,000°F, the thermal-protection panels were also of Rene 41 rather than of a refractory. Measuring 12 by 45 inches, these panels were spot-welded directly to the corrugations of the substructure. For the wing undersurface, and for other areas that were hotter than 2,000°F, designers specified an insulated structure. Standoff clips, each with four legs, were riveted to the underlying corrugations and supported the refractory panels, which also were 12 by 45 inches in size.

The space between the panels and the substructure was to be filled with insulation. A survey of candidate materials showed that most of them exhibited a strong tendency to shrink at high temperatures. This was undesirable; it increased the rate of heat transfer and could create uninsulated gaps at seams and corners. Q-felt, a silica fiber from Johns-Manville, also showed shrinkage. However, nearly all of it occurred at 2,000°F and below; above 2,000°F, further shrinkage was negligible. This meant that Q-felt could be “pre-shrunk” through exposure to temperatures above 2,000°F for several hours. The insulation that resulted had density no greater than 6.2 pounds per cubic foot, one-tenth that of water. In addition, it withstood temperatures as high as 3,000°F.31

TZM outer panels, insulated with Q-felt, proved suitable for wing leading edges. These were designed to withstand equilibrium temperatures of 2,825°F and short – duration overtemperatures of 2,900°F. However, the nose cap faced temperatures of 3,680°F, along with a peak heat flux of 143 BTU per square foot-second. This cap had a radius of curvature of 7.5 inches, making it far less blunt than the Project Mercury heat shield that had a radius of 120 inches.32 Its heating was correspondingly more severe. Reliable thermal protection of the nose was essential, and so the program conducted two independent development efforts that used separate approaches. The firm of Chance Vought pursued the main line of activity, while Boeing also devised its own nose-cap design.

The work at Vought began with a survey of materials that paralleled Boeings review of refractory metals for the thermal-protection panels. Molybdenum and columbium had no strength to speak of at the pertinent temperatures, but tungsten retained useful strength even at 4,000°F. However, this metal could not be welded, while no known coating could protect it against oxidation. Attention then turned to nonmetallic materials, including ceramics.

Ceramics of interest existed as oxides such as silica and magnesia, which meant that they could not undergo further oxidation. Magnesia proved to be unsuitable because it had low thermal emittance, while silica lacked strength. However, carbon in the form of graphite showed clear promise. It held considerable industrial experience; it was light in weight, while its strength actually increased with temperature. It oxidized readily but could be protected up to 3,000°F by treating it with silicon, in a vacuum and at high temperatures, to form a thin protective layer of silicon carbide. Near the stagnation point, the temperatures during re-entry would exceed that level. This brought the concept of a nose cap with siliconized graphite as the primary material, with an insulating layer of a temperature-resistant ceramic covering its forward area. With graphite having good properties as a heat sink, it would rise in temperature uniformly and relatively slowly, while remaining below the 3,000°F limit through the full time of re-entry.

Suitable grades of graphite proved to be available commercially from the firm of National Carbon. Candidate insulators included hafnia, thoria, magnesia, ceria, yttria, beryllia, and zirconia. Thoria was the most refractory but was very dense and showed poor resistance to thermal shock. Hafnia brought problems of availability and of reproducibility of properties. Zirconia stood out. Zirconium, its parent metal, had found use in nuclear reactors; the ceramic was available from the Zirconium Corporation of America. It had a melting point above 4,500°F, was chemically stable and compatible with siliconized graphite, offered high emittance with low thermal conductivity, provided adequate resistance to thermal shock and thermal stress, and lent itself to fabrication.33

For developmental testing, Vought used two in-house facilities that simulated the flight environment, particularly during re-entry. A ramjet, fueled with JP-4 and running with air from a wind tunnel, produced an exhaust with velocity up to 4,500 feet per second and temperature up to 3,500°F. It also generated acoustic levels above 170 decibels, reproducing the roar of a Titan III booster and showing that samples under test could withstand the resulting stresses without cracking. A separate installation, built specifically for the Dyna-Soar program, used an array of propane burners to test full-size nose caps.

The final Vought design used a monolithic shell of siliconized graphite that was covered over its full surface by zirconia tiles held in place using thick zirconia pins. This arrangement relieved thermal stresses by permitting mechanical movement of the tiles. A heat shield stood behind the graphite, fabricated as a thick disk-shaped container made of coated TZM sheet metal and fdled with Q-felt. The nose cap attached to the vehicle with a forged ring and clamp that also were of coated TZM. The cap as a whole relied on radiative cooling. It was designed to be reusable; like the primary structure, it was to withstand four re-entries under the most severe conditions permitted.34

The backup Boeing effort drew on that company’s own test equipment. Study of samples used the Plasma Jet Subsonic Splash Facility, which created a jet with temperature as high as 8,000°F that splashed over the face of a test specimen. Full-scale nose caps went into the Rocket Test Chamber, which burned gasoline to produce a nozzle exit velocity of 5,800 feet per second and an acoustic level of 154 decibels. Both installations were capable of long-duration testing, reproducing conditions during re-entries that could last for 30 minutes.35

The Boeing concept used a monolithic zirconia nose cap that was reinforced against cracking with two screens of platinum-rhodium wire. The surface of the cap was grooved to relieve thermal stress. Like its counterpart from Vought, this design also installed a heat shield that used Q-felt insulation. However, there was no heat sink behind the zirconia cap. This cap alone provided thermal protection at the nose through radiative cooling. Lacking both pinned tiles and an inner shell, its design was simpler than that ofVought.36

Its fabrication bore comparison to the age-old work of potters, who shape wet clay on a rotating wheel and fire the resulting form in a kiln. Instead of using a potter’s wheel, Boeing technicians worked with a steel die with an interior in the shape of a bowl. A paper honeycomb, reinforced with Elmer’s Glue and laid in place, defined the pattern of stress-relieving grooves within the nose cap surface. The working material was not moist clay, but a mix of zirconia powder with binders, internal lubricants, and wetting agents.

With the honeycomb in position against the inner face of the die, a specialist loaded the die by hand, filling the honeycomb with the damp mix and forming layers of mix that alternated with the wire screens. The finished layup, still in its die, went into a hydraulic press. A pressure of 27,000 psi compacted the form, reducing its porosity for greater strength and less susceptibility to cracks. The cap was dried at 200°F, removed from its die, dried further, and then fired at 3,300°F for 10 hours. The paper honeycomb burned out in the course of the firing. Following visual and x-ray inspection, the finished zirconia cap was ready for machining to shape in the attachment area, where the TZM ring-and-clamp arrangement was to anchor it to the fuselage.37

The nose cap, outer panels, and primary structure all were built to limit their temperatures through passive methods: radiation, insulation. Active cooling also played a role, reducing temperatures within the pilots compartment and two equipment bays. These used a “water wall,” which mounted absorbent material between sheet – metal panels to hold a mix of water and a gel. The gel retarded flow of this fluid, while the absorbent wicking kept it distributed uniformly to prevent hot spots.

During reentry, heat reached the water walls as it penetrated into the vehicle. Some of the moisture evaporated as steam, transferring heat to a set of redundant water-glycol cooling loops resembling those proposed for Brass Bell of 1957. In Dyna-Soar, liquid hydrogen from an onboard supply flowed through heat exchangers and cooled these loops. Brass Bell had called for its warmed hydrogen to flow through a turbine, operating the onboard Auxiliary Power Unit. Dyna-Soar used an arrangement that differed only slightly: a catalytic bed to combine the stream of warm hydrogen with oxygen that again came from an onboard supply. This produced gas that drove the turbine of the Dyna-Soar APU, which provided both hydraulic and electric power.

A cooled hydraulic system also was necessary to move the control surfaces as on a conventional aircraft. The hydraulic fluid operating temperature was limited to 400°F by using the fluid itself as an initial heat-transfer medium. It flowed through an intermediate water-glycol loop that removed its heat by cooling with hydrogen. Major hydraulic system components, including pumps, were mounted within an actively cooled compartment. Control-surface actuators, along with their associated valves and plumbing, were insulated using inch-thick blankets of Q-felt. Through this combination of passive and active cooling methods, the Dyna-Soar program avoided a need to attempt to develop truly high-temperature hydraulic arrangements, remaining instead within the state of the art.38

Specific vehicle parts and components brought their own thermal problems. Bearings, both ball and antifriction, needed strength to carry mechanical loads at high temperatures. For ball bearings, the cobalt-base superalloy Stellite 19 was known to be acceptable up to 1,200°F. Investigation showed that it could perform under high load for short durations at 1,350°F. However, Dyna-Soar needed ball bearings qualified for 1,600°F and obtained them as spheres of Rene 41 plated with gold. The vehicle also needed antifriction bearings as hinges for control surfaces, and here there was far less existing art. The best available bearings used stainless steel and were suitable only to 600°F, whereas Dyna-Soar again faced a requirement of 1,600°F. A survey of 35 candidate materials led to selection of titanium carbide with nickel as a binder.39

Antenna windows demanded transparency to radio waves at similarly high temperatures. A separate program of materials evaluation led to selection of alumina, with the best grade being available from the Coors Porcelain Company. Its emit – tance had the low value of 0.4 at 2,500°F, which meant that waveguides beneath these windows faced thermal damage even though they were made of columbium alloy. A mix of oxides of cobalt, aluminum, and nickel gave a suitable coating when fired at 3,000°F, raising the emittance to approximately O.8.40

The pilot needed his own windows. The three main ones, facing forward, were the largest yet planned for a manned spacecraft. They had double panes of fused silica, with infrared-reflecting coatings on all surfaces except the outermost. This inhibited the inward flow of heat by radiation, reducing the load on the active cooling of the pilot’s compartment. The window frames expanded when hot; to hold the panes in position, the frames were fitted with springs of Rene 41. The windows also needed thermal protection, and so they were covered with a shield of D-36.

The cockpit was supposed to be jettisoned following re-entry, around Mach 5, but this raised a question: what if it remained attached? The cockpit had two other windows, one on each side, which faced a less severe environment and were to be left unshielded throughout a flight. The test pilot Neil Armstrong flew approaches and landings with a modified Douglas F5D fighter and showed that it was possible to land Dyna-Soar safely with side vision only.41

The vehicle was to touch down at 220 knots. It lacked wheeled landing gear, for inflated rubber tires would have demanded their own cooled compartments. For the same reason, it was not possible to use a conventional oil-filled strut as a shock absorber. The craft therefore deployed tricycle landing skids. The two main skids, from Goodyear, were ofWaspaloy nickel steel and mounted wire bristles of Rene 41. These gave a high coefficient of friction, enabling the vehicle to skid to a stop in a planned length of 5,000 feet while accommodating runway irregularities. In place of the usual oleo strut, a long rod of Inconel stretched at the moment of touchdown and took up the energy of impact, thereby serving as a shock absorber. The nose skid, from Bendix, was forged from Rene 4l and had an undercoat of tungsten carbide to resist wear. Fitted with its own energy-absorbing Inconel rod, the front skid had a reduced coefficient of friction, which helped to keep the craft pointing straight ahead during slideout.42

Through such means, the Dyna-Soar program took long strides toward establishing hot structures as a technology suitable for operational use during re-entry from orbit. The X-15 had introduced heat sink fabricated from Inconel X, a nickel steel. Dyna-Soar went considerably further, developing radiation-cooled insulated structures fabricated from Rene 41 superalloy and from refractory materials. A chart from Boeing made the point that in 1958, prior to Dyna-Soar, the state of the art for advanced aircraft structures involved titanium and stainless steel, with temperature limits of 600°F. The X-15 with its Inconel X could withstand temperatures above 1,200°F. Against this background, Dyna-Soar brought substantial advances in the temperature limits of aircraft structures:43

|

TEMPERATURE LIMITS BEFORE AND AFTER DYNA-SOAR (in °F)

|

Element

|

1258

|

1261

|

|

Nose cap

|

3,200

|

4,300

|

|

Surface panels

|

1,200

|

2,750

|

|

Primary structure

|

1,200

|

1,800

|

|

Leading edges

|

1,200

|

3,000

|

|

Control surfaces

|

1,200

|

1,800

|

|

Bearings

|

1,200

|

1,800

|

|

Meanwhile, while Dyna-Soar was going forward within the Air Force, NASA had its own approaches to putting man in space.

Heat Shields for Mercury and Corona

In November 1957, a month after the first Sputnik reached orbit, the Soviets again startled the world by placing a much larger satellite into space, which held the dog Laika as a passenger. This clearly presaged the flight of cosmonauts, and the question then was how the United States would respond. No plans were ready at the moment, but whatever America did, it would have to be done quickly.

HYWARDS, the nascent Dyna-Soar, was proceeding smartly. In addition, at North American Aviation the company’s chief engineer, Harrison Storms, was in Washington, DC, with a concept designated X-15B. Fitted with thermal protection for return from orbit, it was to fly into space atop a cluster of three liquid-fueled boosters for an advanced Navaho, each with thrust of 415,000 pounds.44 However, neither HYWARDS nor the X-15B could be ready soon. Into this breach stepped Maxime Faget of NACA-Langley, who had already shown a talent for conceptual design during the 1954 feasibility study that led to the original X-15-

In 1958 he was a branch chief within Langley’s Pilotless Aircraft Research Division. Working on speculation, amid full awareness that the Army or Air Force might win the man-in-space assignment, he initiated a series of paper calculations and wind-tunnel tests of what he described as a “simple nonlifting satellite vehicle which follows a ballistic path in reentering the atmosphere.” He noted that an “attractive feature of such a vehicle is that the research and production experiences of the ballistic-missile programs are applicable to its design and construction,” and “since it follows a ballistic path, there is a minimum requirement for autopilot, guidance, or control equipment.”45

In seeking a suitable shape, Faget started with the heat shield. Invoking the Allen – Eggers principle, he at first considered a flat face. However, it proved to trap heat by interfering with the rapid airflow that could carry this heat away. This meant that there was an optimum bluntness, as measured by radius of curvature.

Calculating thermal loads and heat-transfer rates using theories of Lees and of Fay and Riddell, and supplementing these estimates with experimental data from his colleague William Stoney, he considered a series of shapes. The least blunt was a cone with a rounded tip that faced the airflow. It had the highest heat input and the highest peak heating rate. A sphere gave better results in both areas, while the best estimates came with a gently rounded surface that faced the flow. It had only two-thirds the total heat input of the rounded cone—and less than one-third the peak heating rate. It also was the bluntest shape of those considered, and it was selected.46

With a candidate heat-shield shape in hand, he turned his attention to the complete manned capsule. An initial concept had the shape of a squat dome that was recessed slightly from the edge of the shield, like a circular Bundt cake that does not quite extend to the rim of its plate. The lip of this heat shield was supposed to

produce separated flow over the afterbody to reduce its heating. When tested in a wind tunnel, however, it proved to be unstable at subsonic speeds.

Faget’s group eliminated the open lip and exchanged the domed afterbody for a tall cone with a rounded tip that was to re-enter with its base end forward. It proved to be stable in this attitude, but tests in the 1 l-inch Langley hypersonic wind tunnel showed that it transferred too much heat to the afterbody. Moreover, its forward tip did not give enough room for its parachutes. This brought a return to the domed afterbody, which now was somewhat longer and had a cylinder on top to stow the chutes. Further work evolved the domed shape into a funnel, a conic frustum that retained the cylinder. This configuration provided a basis for design of the Mercury and later of the Gemini capsules, both of which were built by the firm of McDonnell Aircraft.47

Choice of thermal protection quickly emerged as a critical issue. Fortunately, the thermal environment of a re-entering satellite proved to be markedly less demanding than that of an ICBM. The two vehicles were similar in speed and kinetic energy, but an ICBM was to slam back into the atmosphere at a steep angle, decelerating rapidly due to drag and encountering heating that was brief but very severe. Reentry from orbit was far easier, taking place over a number of minutes. Indeed, experimental work showed that little if any ablation was to be expected under the relatively mild conditions of satellite entry.

But satellite entry involved high total heat input, while its prolonged duration imposed a new requirement for good materials properties as insulators. They also had to stay cool through radiation. It thus became possible to critique the usefulness of ICBM nose-cone ablators for the prospective new role of satellite reentry.48

Fieat of ablation, in BTU per pound, had been a standard figure of merit. For satellite entry, however, with little energy being carried away by ablation, it could be irrelevant. Phenolic glass, a fine ICBM material with a measured heat of 9,600 BTU per pound, was unusable for a satellite because it had an unacceptably high thermal conductivity. This meant that the prolonged thermal soak of re-entry could have time enough to fry a spacecraft. Teflon, by contrast, had a measured heat only one-third as large. It nevertheless made a superb candidate because of its excellent properties as an insulator.49

Such results showed that it was not necessary to reopen the problem of thermal protection for satellite entry. With appropriate caveats, the experience and research techniques of the ICBM problem could carry over to this new realm. This background made it possible for the Central Intelligence Agency to build operational orbital re-entry vehicles at a time when nose cones for Atlas were still in flight test.

This happened beginning in 1958, when Richard Bissell, a senior manager within the CIA, launched a highly classified reconnaissance program called Corona. General Electric, which was building nose cones for Atlas, won a contract to build the film-return capsule. The company selected ablation as the thermal-protection method, with phenolic nylon as the ablative material.50

The second Corona launch, in April 1959, flew successfully and became the world’s first craft to return safely from orbit. It was supposed to come down near Hawaii, and a ground controller transmitted a command to have the capsule begin re-entry at a particular time. However, he forgot to press a certain button. The director of the recovery effort, Lieutenant Colonel Charles “Moose” Mathison, then learned that it would actually come down near the Norwegian island of Spitzber – gen.

Mathison telephoned a friend in Norway’s air force, Major General Tufte John – sen, and told him to watch for a small spacecraft that was likely to be descending by parachute. Johnsen then phoned a mining company executive on the island and had him send out ski patrols. A three-man patrol soon returned with news: They had seen the orange parachute as the capsule drifted downward near the village of Barentsburg. That was not good because its residents were expatriate Russians. General Nathan Twining, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, summarized the craft’s fate in a memo: “From concentric circular tracks found in the snow at the suspected impact point and leading to one of the Soviet mining concessions on the island, we strongly suspect that the Soviets are in possession of the capsule.”51

Meanwhile, NASA’s Maxime Faget was making decisions concerning thermal protection for his own program, which now had the name Project Mercury. He was well aware of ablation but preferred heat sink. It was heavier, but he doubted that industrial contractors could fabricate an ablative heat shield that had adequate reliability.52

The suitability of ablation could not be tested by flying a subscale heat shield atop a high-speed rocket. Nothing less would do than to conduct a full-scale test using an Atlas ICBM as a booster. This missile was still in development, but in December 1958 the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division agreed to provide one Atlas C within six months, along with eight Atlas Ds over the next several years. This made it possible to test an ablative heat shield for Mercury as early as September 1959.53

The contractor for this shield was General Electric. The ablative material, phenolic-fiberglass, lacked the excellent insulating properties of Teflon or phenolic – nylon. Still, it had flown successfully as a ballistic-missile nose cone. The project engineer Aleck Bond adds that “there was more knowledge and experience with fiberglass-phenolic than with other materials. A great deal of ground-test information was available…. There was considerable background and experience in the fabrication, curing, and machining of assemblies made of Fiberglass.” These could be laid up and cured in an autoclave.54

The flight test was called Big Joe, and it showed conservatism. The shield was heavy, with a density of 108 pounds per cubic foot, but designers added a large safety factor by specifying that it was to be twice as thick as calculations showed to be necessary. The flight was to be suborbital, with range of 1,800 miles but was to simulate a re-entry from orbit that was relatively steep and therefore demanding, producing higher temperatures on the face of the shield and on the afterbody.55

Liftoff came after 3 a. m., a time chosen to coincide with dawn in the landing area so as to give ample daylight for search and recovery. “The night sky lit up and the beach trembled with the roar of the Rocketdyne engines,” notes NASA’s history of Project Mercury. Two of those engines were to fall away during ascent, but they remained as part of the Atlas, increasing its weight and reducing its peak velocity by some 3,000 feet per second. What was more, the capsule failed to separate. It had an onboard attitude-control system that was to use spurts of compressed nitrogen gas to turn it around, to enter the atmosphere blunt end first. But this system used up all its nitrogen trying fruitlessly to swing the big Atlas that remained attached. Separation finally occurred at an altitude of 345,000 feet, while people waited to learn what would happen.56

The capsule performed better than planned. Even without effective attitude control, its shape and distribution of weights gave it enough inherent stability to turn itself around entirely through atmospheric drag. Its reduced speed at re-entry meant that its heat load was only 42 percent of the planned value of 7,100 BTU per square foot. But a particularly steep flight-path angle gave a peak heating rate of 77 percent of the intended value, thereby subjecting the heat shield to a usefully severe test. The capsule came down safely in the Atlantic, some 500 miles short of the planned impact area, but the destroyer USS Strong was not far away and picked it up a few hours later.

Subsequent examination showed that the heating had been uniform over the face of the heat shield. This shield had been built as an ablating laminate with a thickness of 1.075 inches, supported by a structural laminate half as thick. However, charred regions extended only to a depth of 0.20 inch, with further discoloration reaching to 0.35 inch. Weight loss due to ablation came to only six pounds, in line with experimental findings that had shown that little ablation indeed would occur.57

The heat shield not only showed fine thermal performance, it also sustained no damage on striking the water. This validated the manufacturing techniques used in its construction. The overall results from this flight test were sufficiently satisfactory to justify the choice of ablation for Mercury. This made it possible to drop heat sink from consideration and to go over completely to ablation, not only for Mercury but for Gemini, which followed.58