Perspectives on the Legacy

Alan Bean, for whom life on Skylab was a follow-up to his experience of walking on the moon, said that the station was a vital step in the history of manned spaceflight. “My impression of it was that it was the best possible investment of NASA money,” he said. “It’s so much more valuable than sending one other mission to the moon, which they could have done with that Saturn v.

“It was so much more valuable, I felt, as far as understanding the future of spaceflight and taking the next step. Taking another step on the moon would have been nice, but it wasn’t going to do much different. Different rocks, nothing new particularly. And so we made a breakthrough on another branch of spaceflight, and started out in a way that gave us a foundation.” In retrospect it’s easy to forget how many unknown factors the Skylab crews dealt with, how many things astronauts today are able to take for granted because the Skylab crews proved that they could be done. “My biggest concern before we flew Skylab, or anybody flew Skylab, was, at the end of twenty-eight days, and then at the end of fifty-six days, would we be strong enough to go outside and recover the film and do the work in our space suits? Now it seems like a dumb idea. But I can remember thinking that is one of the real huge hurdles that I wondered if we’d be able to do. As it turned out to be, we stayed just as strong as we were at the beginning.”

Bean said that he regrets the extent to which some of the knowledge gained on Skylab was lost during the decades before the United States once again became involved in long-duration spaceflight. While on orbit, he said, the crewmembers spent time each week answering habitability questions about life on Skylab—everything from how well the equipment worked to what they thought of the colors in the workshop. Their answers were recorded on tape, dumped to the ground, and then written up. “We talked about everything you could think of,” Bean said. He said that, in talking to members of the astronaut corps about the International Space Station project, he’s found that the habitability reports produced based on the experiences of the Skylab crews have gone largely unread.

Bob Crippen agreed: “The one thing that I really worried about was—we did it, then we let it sit up there until it was falling out of the sky, and now we’re starting to finally get a space station up there again.” Crippen said that the time gap between Skylab and the first International Space Station crew was very disappointing to him. “I thought we learned a lot of lessons, and it wasn’t obvious when you get that big of a gap that you can transfer a lot of knowledge. That’s the only disappointment that I felt.” (It is worth noting that this is not due to a lack of trying on the part of the Skylab astronauts, many ofwhom were involved in the planning for the later space station programs either while still at NASA or as contractors.)

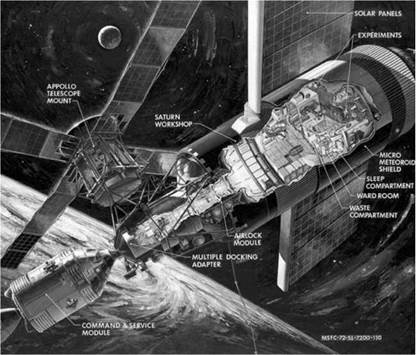

Overall, Crippen said that he was very proud to have been involved in the program. Learning of the problem with the micrometeoroid shield at launch, he said, was one of the lowest points of his career, and the recovery from that disaster amazed him. “I thought we’d lose the entire mission right there when that happened. The way the team worked to pull off getting the thing back flying again I thought was fantastic.” The can-do attitude that began the program, he noted, continued throughout with the work that was done during the mission on such things as changing out the gyros.

“The Russians were over here about that time, and they were impressed at how we could do on-orbit repairs, some of those kinds of things,” Crippen said. “In fact, we took some of those lessons into Space Shuttle, that we needed the capability to do in-flight maintenance on things we didn’t even know we were going to have to work on. So I thought it was a great program. I think everybody that participated in it will tell you that.”

For Bob Schwinghamer also, the effort to save Skylab after its disastrous launch was a defining moment. “I mean, that enormous recovery effort, and the ability to pull that off— in retrospect, you just wonder how people were able to do that in the short time that they did,” he said. “And then the astronauts did their thing. It was something you can remember with pride, everybody that had anything to do with it. It was an uplifting experience.”

The program, Schwinghamer said, lived up to its expectations. “I think it more than did.”

That sentiment was echoed by George Hardy: “I think Skylab was in some ways, without question, the best space program this country has ever had. Now there are some space programs that had maybe higher, greater technical challenges, but I guess if you were to characterize it as ‘bang for the buck,’ I don’t think there’s been a program that’s gotten the bang for the buck that Skylab got.”

Hardy, who went on to be involved in the space station program, also said that he has been disappointed with NASA’s failure to fully capitalize on the lessons learned during Skylab when moving forward. While he noted that many parts of the Skylab experience—such as the lessons learned about crew and ground operations for a long-term program—informally influenced later programs, lessons of other parts of that experience have been largely lost.

“I don’t think there was a formal, structured program for carrying ‘lessons learned’ from Skylab into space station,” he said. “I don’t know exactly why that was. I think for the most part a lot of people working on space station thought to themselves that space station would be so far advanced from Skylab that there wouldn’t be any useful lessons to be learned. And that was a big mistake.”

George Mueller was even harsher in his views on the subject. He was very proud of the accomplishments of Skylab—“I thought it was great”—and very disappointed with what he saw as NASA failing to learn the lessons of that program in the space station project. “The design of the station really did not take advantage of what we learned on Skylab,” he said. “That was my impression the first time I walked through that mock-up; I thought, ‘We haven’t really learned anything.’”

In particular, he said, the decision not to use a heavy lift vehicle, which would have allowed large volumes to be launched into orbit, was a major limitation in the space station program. “Volume is tremendously important in living conditions,” Mueller said. “Engineers want to build everything into little boxes, but if you’re going to live in it, you’d like to have some distance, you’d like to have some privacy, and you’d like to have some things that are pleasing to look at.”

Jack Lousma said that he also is proud of the groundwork that Skylab laid for the future of spaceflight. “I think we demonstrated that you could live and work in space for a long time and do a good job,” he said. “One of the most important legacies was the demonstration of long-duration flight, demonstrating that not only could you survive up there but you could do useful things, that you could work up there like you would in any laboratory back home. We demonstrated that we could do zero-gravity spacewalks. It gave us the confidence to go on to longer missions, having a sense that if you stayed there a year, you’d still be ok.”

Where Are They Now?

Alan Bean

After resigning from nasa in 1981, Bean devoted himself full-time to his painting. He has found a devoted audience for his work, which is based on his experiences as an astronaut on the moon.

Bo Bobko

Bobko flew on his first space mission in 1983 as the pilot of sts-6, the first flight of the Space Shuttle Challenger, seventeen years after he was first selected as an astronaut by the Air Force. Bobko also went on to command missions of his own, Shuttle flights 51-D and 51-j, both in 1985. Bobko left NASA in 1988 to work as an aerospace contractor.

Vance Brand

Despite missing out on the Skylab rescue mission, Brand would fly into space four times—on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project and as commander of the sts – 4, 41-B and STS-35 Space Shuttle missions. After the retirement of John Young in 2004, Brand became the senior member of the astronaut corps still working at NASA, serving as the deputy director for Aerospace Projects at Dryden Flight Research Center until his own retirement in 2008.

Jerry Carr

After leaving NASA in 1977, Carr was heavily involved as a contractor in providing consulting input for the development of the International Space Station. He founded camus, a family owned business that combines his consulting with wife Pat Musick’s art and sculpture.

Pete Conrad

After leaving NASA months after his Skylab experience in 1973, Conrad remained involved in aeronautics and space exploration until his death in 1999 as a result of injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident.

|

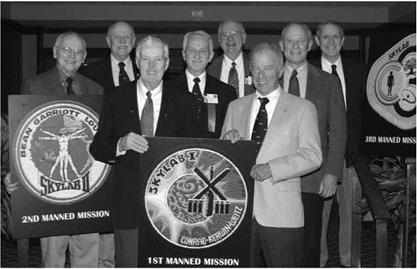

49- At the Skylab Thirtieth Reunion (from left): Alan Bean, Jerry Carr, Joe Kerwin, Owen Garriott, Bill Pogue, Paul Weitz, Jack Lousma, and Ed Gibson. |

Bob Crippen

Crippen, who served as director of Kennedy Space Center before leaving NASA in 1995, was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 2006 in recognition of his role as pilot of sts-i, the first Space Shuttle mission. In addition to serving as pilot of that mission, Crippen commanded the STS-7 and 41c and 41G Shuttle missions.

Owen Garriott

After flying into space one more time on the STS-9 Spacelab mission of the Space Shuttle, Garriott resigned from NASA in 1986 and is now an adjunct professor at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. He spends additional time in charitable activities and as a founder of two new businesses.

Ed Gibson

In addition to working with aerospace contractors after leaving NASA in 1974, Gibson also authored two novels, Reach and In the Wrong Hands. He recently retired as senior vice president and contract manager with Science Applications International Corporation.

Joe Kerwin

Kerwin served as the NASA representative in Australia in 1982 and 1983, then as director of Space and Life Sciences at jsc from 1984 to 1987. He worked

for Lockheed from 1987 to 1996 and finished his career as senior vice president with Wyle Laboratories, retiring in 2004.

Chris Kraft

Per Kraft: “Chris Kraft is now retired and trying to stay compos mentis. He is very proud of his part in the early days of manned spaceflight and especially the Space Shuttle, which has been unfairly maligned by the media, NASA and other ill-informed engineers and scientists.”

Chuck Lewis (msfc)

After Skylab, Lewis spent a few years in the propulsion division, working on the srb booster separation motors among other things. He then worked in crew training and interface for Spacelab missions. At retirement in 1996, he was Chief of the Mission Training Division at msfc, where he had the pleasure of watching young engineers continue to support the flight crew with great training and man-systems design for the remaining Spacelab flights and well into the iss era.

Jack Lousma

Lousma made one more spaceflight after Skylab, as commander of Columbia’s STS-3 mission, the third Space Shuttle flight, in March 1982. He resigned from NASA in 1983. In 1984 he won the Republican primary for one of Michigan’s seats in the U. S. Senate but was defeated by the incumbent in the general election. Since that time, he has been involved in several technology – related businesses and still lives in Michigan with his wife Gratia.

George Mueller

Mueller continues to be involved in the advancement of space transportation, actively pursuing the fundamental physical requirement for a viable space society: a completely reusable space vehicle capable of delivering tons of payload to low Earth orbit at a cost of dollars per pound, a goal he describes as well within our reach.

Bill Pogue

After leaving NASA, Pogue turned his attention to the next generation of space stations, serving as a consultant for what became the International Space Station, and to the next generation of explorers, making spaceflight accessible through his books How Do You Go to the Bathroom in Space and Space Trivia.

Don Puddy

Puddy served as a Shuttle flight director and as the lead flight director on the Shuttle approach and landing tests. He subsequently served as a special assistant to the NASA administrator, as the deputy director of the Dryden Research Center, and as the director of Flight Crew Operations at jsc. After retirement he succumbed to cancer.

Rusty Schweickart

Schweickart left NASA in 1977 to join the staff of Gov. Jerry Brown of California. He served as commissioner of energy in California for nearly six years then as a senior executive in several space and telecommunications companies. He now chairs the board of the B612 Foundation, which champions plans to protect the earth from asteroid impacts. He is the founder and past president of the Association of Space Explorers, the international professional society of astronauts and cosmonauts.

Bob Schwinghamer

Schwinghamer retired from Marshall as assistant director, technical in January 1999. Since that time he has consulted for NASA on the Shuttle Columbia accident and also on the successful “return to flight” of the Space Shuttle. He still resides in Huntsville.

Phil Shaffer

After Skylab Shaffer served as a principal interface between jsc’s flight operations organizations and Rockwell International for establishing operations requirements for the Space Shuttle. In the early 1980s after leaving NASA, he served as a consultant supporting several of the NASA contractors supporting the Shuttle and the Space Station. Phil Shaffer died in June 2007.

Jim Splawn

As a director of marketing and business development for Boeing, Splawn is responsible for acquiring new business through advanced technology applications for the Department of Defense. These technologies may be used in either an offense or defense weapon mode, including missiles. Applications include military operations, both local and foreign, and Homeland Security.

J. R. Thompson

Before leaving NASA, Thompson served as deputy administrator at NASA headquarters and as director of Marshall Space Flight Center. Today he serves as vice chairman, president, and chief operating officer of Orbital Sciences.

Bill Thornton

Scientist astronaut Bill Thornton waited sixteen years after his selection by NASA before he first flew on sts-8 in 1983. The mission further explored human adaptation to the microgravity environment, with much of the research being performed with equipment he had designed. Thornton flew once more, on the Spacelab-3 51-B mission in 1985, on which he was responsible for medical investigations. He left NASA in 1994 and returned to academia at the University of Texas Medical Branch and the University of Houston, Clear Lake.

Paul Weitz

Weitz commanded the sixth Shuttle mission in 1983. He served as deputy chief of the astronaut office until 1986, then was appointed deputy director of the Johnson Space Center. He retired from NASA in 1994 and moved to Flagstaff, Arizona, where he says he “took up birding, fly fishing, and loafing, in reverse order.”

Nine men were fortunate to live the Skylab experience, and their names will forever be recorded as NASA’s first to truly live and work in space.

But while the names of those nine are the best known of the Skylab program, their voyages were made possible by thousands of men and women who helped establish an outpost on the frontier of space.

“Their legacy is that it is possible for humans to live and work in space for extended periods—but only with a terrific ‘Home Earth’ team to support them,” Joe Kerwin said. “We, the homesteaders, thank them for their gifts of problem solving, support, and cooperation.

“It was fun to learn how to fly.”

|

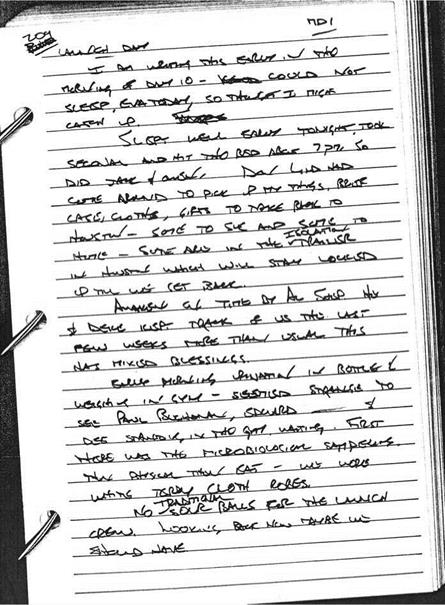

The following is the complete text of the diary that Skylab II commander Alan Bean kept during his time on the space station. It is presented unexpurgated and largely unmodified, with the primary exception of formatting. Bean’s handwriting does not differentiate between capital and lowercase letters, and the diary included minimal use of punctuation. For the sake of readability, those issues have been addressed.

Bean numbered the entry with the day of the year on which it was written, so the first entry, 209, for example, refers to the 209th day of the year, 28 July 1973.

209

Launch Day

(I am writing this early in the morning of day 10—Could not sleep, eva today, so thought I might catch up.)

Slept well early tonight, took Seconal and hit the bed about 7 p. m., so did Jack and Owen.

Don Lind had come around to pick up my things, brief case, clothes, gifts to take back to Houston—some to Sue and some to home—Some are in the isolation trailer in Houston which will stay locked up till we get back.

Awakened on time by Al Shepard. He and Deke kept track of us the last few weeks more than usual. This has mixed blessings.

Early morning urination in bottle and weighing in gym—seemed strange to see Paul Buchanan, Edward & Dee standing in the gym waiting. First there was the microbiological samples. Then physical—Then eat—We wore white terry cloth robes.

No traditional sour balls for the launch crew. Looking back now, maybe we should have.

Al Shepard rode in van as far as the Launch Control Center. I watched him because he held the rdz book—when he got up to get off, he forgot he had it and I had to ask. On the way he told us he was the last minute back up—he then mentioned Glenn having his suit at the suit room prior to Al’s first flight.

4, 3 (engine noise and damn the machine starts to shake), 2, 1, more and more violent shaking—it seems to want to go like a car spinning its wheels

о—God, and you feel it pull away from the launch site—vibration, rough jerking, much much feeling of an unleashed power house wanting to go skyward —almost the same feel in reverse when you step off the high diving board—You can hear and feel the beast start to accelerate. Jack and Owen are spellbound, so am I for that matter. Lift off, tower clear, whew, that’s a big one, roll & pitch program. I call—my voice sounds ok, don’t sound too nervous, that’s good —Jack and Owen ok.

210

Slept in the ows sleep compartments last night—Place not fully activated but better than csm. Slept pretty good because I was so tired, and sorta sick to my stomach. Owen looked so-so but Jack looked real bad.

Stuffed up head feeling present and will probably be with us the rest of the flight—Nose gets lots of buggers in it & when I blow it it expels blood. Dry climates like Denver do the same.

May have had the straps too tight on the bunk last night.

Breakfast in csm, no water yet in the workshop—Not a pleasant get together—Nobody wanted to eat but knew we had to. No one wanted to think of the things we had to do today— I was behind with stowage, putting the rate gyros together (a last minute add on) and trouble shooting the condensate leak. In fact spent most of today responding to ground request for troubleshooting the leak—seemed disorganized—kept doing things too fast, causing delays, lost 50% of my time today for things I should not have let loose.

211

We are farting a lot but not belching much —Joe Kerwin said we would have to learn to handle lots of gas.

Got to stop responding to ground so fast and just dropping what I am doing—causes us to run behind on the time line. Do not know just what to do about this.

I am feeling good in the morning and between meals. Meals themselves tough to get through.

Still losing a lot of things, too big a hurry. Wish the flight planners would let up. The time taken to trouble shoot the condensate system shoots the whole timeline. Got to stay on schedule.

Floated too much at a work station—wish my triangle shoes were adjusted correctly.

Guess we had the failure. Because except for a stuck thruster it’s about the worst we can expect — We handled it well but not perfectly.

гіг

Jack was taking a cooked fecal out of the dryer—laughing—well, here is a real nice ripe one, I said, bet you are a good pitza cook. No, said Jack, pancakes.

We had too many fecals and vomitus to cook—

(Look at down voice and we can see what we did each day in ref. to Flt Plan.)

213

Without triangle shoes you can get a free return to our early ancestors; namely holding and swinging feet, legs, arms and wedging feet and arms, feet and butt or feet and back to hold position, you get good at it where you do not have to pick out specific place for each limb or which technique to use, but it comes naturally.

All were in extremely high spirits today, first day we all feel good.

Discuss location of items in particular pockets—left lower leg, trash.

Owen said that today we ought to ask for a reduction in our insurance rates because we were no longer running the risk of drowning or auto accident.

217

Left sal vent open last night after water dump. Thought I was so good at it, did not use check list—fooled because this was first night without experiment in SAL.

Wonder what happens when we cross the international date line multiple times a day. Well, no matter.

Saw Cape of Good Hope.

Owen let Arabella out of the vial. She had been in there since____ days

prior to launch. She had not come out so Owen got the vial off the cage, opened the door, shook her out where she immediately bounced back and forth, front to back, four or five times, then locked onto screen panels at the box edge provided for visualization—there she sits clutching the screen. Owen and I talked of giving spider food because she has not moved one half day. Owen said “no” because when she gets hungry is when she spins her web. (More description.) She can live two-three weeks without if she has too.

First back-to-back erep. Jack vts sites Lake Michigan. But got Baltimore instead. Or Washington, his prime site.

Saw what we thought was a salt flat but turned out to be a glacier in Chile. We could see Cape Horn — Cape Horn and Good Hope all in one day, fantastic.

Owen wanted to know if we had tried to urinate upside in the head. He said it psychological tough. Jack said he tried it and he peed right in his eye.

Diving thru workshop different than in water—here the speed that you move (translate) is controlled entirely by your push off so for some spins you can have a D, і Уг, 2 У2, 3 У2, etc. Difficult to push off straight and to get speeds you want. You must watch your progress as you spin—it’s tough to learn but to keep from hitting objects, it’s a must.

It was a great day — first back to back erep and it came off perfect. Jack and Owen good spirits for eva tomorrow—we worked all afternoon and evening on prep, much more fun than on Earth in ig.

Owen worked 22 hours today because he counted his sleep cap time. Talked with Sue over Guam tonight. She asked about rdz from Dave Scott. He said і quad out at so some skill required—he is going to Flight Research Center, great! Every day is filled with memorable experiences—sites, sounds, emotions, hope, fear, courage, friendship. I just wish we could go home to our wives at night.

My urine volume lower than Owen and Jack. Been drinking a lot but must do better. Been concentrating on eating too much. Owen said meals were the high point of a day on Earth and here too. Only difference is there it’s the start, up here it’s when you finish. I got ahead today with a snack during erep, don’t ever fall behind.

I cut a hole in the bottom of my sleeping bag near the feet—too hot, had to tie a knot to keep from freezing in the early morning.

Heard about leak in am primary and secondary cooling loop. Pri should last 17 days and secondary 60 days. Wonder what ingenious fix they will come up with.

No csm master alarm today.

Almost a no mistake day. But just prior to sleep Crip calls and ask we turn the ess (medical) off. I had just ridden the bike.

218

eva day. I had a tough time sleeping. ok for first 6 hours or so then off and on—finally writing at normal wake up time, iiooz (0600 Houston) because they let us sleep late. Bed is great. I am going to patent it when I get home. The bungee straps and netting for the head and the pillows were my idea. Might come in use someday because no other simple way to make og feel like Earth.

Jack sleeps next to me then Owen at end—the reason, his sleep cap equipment fits better.

Funny how good we feel now, I think we all would have said “to hell with this, let’s go home.” I—we were not old enough to know time would pass and we would feel better. No one ever said it in words but that was the way we all looked at each other around day 2 and 3.

Sleeping is different here because the “bed clothes” do not tend to rest or touch your body. This causes large air spaces about your body, that your body heat just doesn’t heat. It’s difficult to snuggle down. Have to put undershirts (long) and t-shirt on during the night. I cut feet out of the long handles then use them for pajamas. Also I mod’ed my bed by cutting a hole in the netting near the feet, too cold at night so close it up with a knot.

Little worried, Funny—Owen’s pcu is #013 and his umbilical is #13. I’m not superstitious, but. . .

Started taking food pill supplements today. Kit is junkeys paradise.

Jack discovered new way to shake urine to minimize bubbles. I called ground and said, “we even have our professionals—Owen atm checkout, me condensate dump, Jack urine shaking.”

eva thoughts

Owen was having trouble with the twin poles—the elastic was tight at either end of the pole plate and as he pulled the poles out the rubber grommet locking the lock nut would tend to roll off. We had not pulled out any poles at the pre check last night because we were afraid too, we might break the elastic. We could not even break it today as Owen tried. He used his head and stopped—thought of a new approach, right foot out of foot restraint to pull pole the right end and left out to take the poles.

We are going to have the twin pole sail configuration on our medallion when we get back.

Watching out the STS window as Jack worked in the dark; I could not look at him in the light as he was too close to the sun, it was fantastic to see the sunrise. It began as a light blue band which grew with a fine yellow rim near the Earth’s limb—the blue gets larger then.

The line with the gentle curvature of the Earth and the fact it became dimmer as you looked off to either side of the sun’s future position.

Just before sun up you could see dim flashes of light toward the horizon where thunderstorms were playing. This pin pointed the coming horizon

which was not discernable against the dark of the Earth from the lighted cabin.

Gold grows at last 15 sec to cover much of dark blue then bright orange and a bright glint as the sun. As it rises the Earth’s horizon moves slowly from head to toe on Jack as he is silhouetted against the blue line. It gives the feeling of going around a big planet, a big ball rather than just a disk moving from in front of the eye. The science fiction movie effect was fantastic.

Pole deploy was also difficult because line got tangled by 180 degrees—had to roll back the grommet and then unscrew the nut and remove it.

Poles nice and straight and not bobbing around—white tape at forward edge foil/nylon sail stuck together—did not want to unfold but Jack pulled it in and then out again as sun sets.

Jack said, being out on the sun end, was a little like Peter Pan—or that you were riding a big white horse—feet spread wide across the whole world—the Earth is visible on both sides, at the same times and you can see 360 degrees—riding backwards.

Jack kept teleprinter flight plan as he was going to bed. Owen ask why—Jack said “I want to keep the memorable and unique days”—I said “don’t lose your day off flight plan then.”

219

Passed the lbnp today for the first time. Think I was too far in it and squeeze around stomach cut off blood, will move saddle from 9 to 6.

Did a lot of flying about the workshop just before sleep tonight. Skill needed, but great relaxer. Wish Owen would move Arabella.

Arabella finished her web perfectly. When Owen told Jack at breakfast, Jack said “well that’s good, I like to see a spider do something at least once in a while.”

220

Lost our day 5 menu card today. Had to fake it at breakfast. I finally found it as I was looking in the toolbox for a Phillips head screw driver for the wardroom foot restraints. My green copy of Childhood’s End floated by. If you wait long enough, everything lost will float by. A dynamic environment no one can be stranded in center of a space because small air currents have an effect.

Tried to fly (like swimming) last night. But air currents much more dominant.

Fire and rapid Delta p drill today. Owen needs them the most but hates them the worst. I try to stick with him and do this together, Jack goes alone—when I am distracted, Owen will be doing other things not drill related and I must get him back.

Slept better last night (upside down) because it was cooler from the twin boom sun shade.

Arabella ate her web last night and spun another perfect one.

222

Day off— we had mixed emotions. We were tired and needed rest yet our chance to do good work was almost one-fourth over. When each flight hour represents 13-14 Earth training hours then you can make worthwhile a lot of pre-flight effort with a little extra in flight effort. We did however do some atm and some SO19. We asked for extra plus housekeeping. Wipe, dry biocide wipe, the place is immaculate and not a predatory germ within miles, much less traveling at 18,000 mph.

Got a thrill today. Tried to put our a urine bag with the metal fine filter for the head in it [the Trash Airlock] in addition to three urine bags. It would not eject. I tried to close the doors and breathed a real sigh of relief as it came closed. I removed the filter from the now shortened bag and tried again, this time it moved 1” or so then stuck. I tried gingerly to close the door but this time it would not. My heart was beating fast. Can this be happening to us? I tried the ejection handle again, and no luck, the door was stuck. Finally the only way was to force it. I rapped it again and again at first no success, but finally a little at a time then she broke free. My heart still beat fast but maybe a lesson was learned. Why did they not build the lock as an inverted cone so whatever was in there could always be moved down the ever expanding diameter.

Owen did the spider TV three times. Once because he recorded it all on channel A, once because the TV select switch was in the atm and not ows position, the last time it was okay. He got behind and I did some of his housekeeping as he was still up when Jack and I were headed for bed. Jack said “Owen, do you have anything left I can help you with? ” Owen said “no.” But that’s the way Jack is. Noticed Jack uses aftershave on his crotch. Old Spice after shave and skin conditioner complete with a NASA part number.

Notice we do not seem to reflex to catch something when we drop it as we did the first few days. It’s enjoyable to just let a heavy object float nearby.

223

Jack replied to Hank Hartsfield, he felt real good today. Owen said, uh oh, Jack must be sick again. Go look for a full vomitus bag in his bunk room.

Had a PP02 low caution alarm—ground said, we can inhibit as it was erratic recently.

We moved our suits up to the mda getting them closer to the csm and out of the way for the maneuvering experiment later in the week—we moved three silent friends and stashed two at the front end of the mda and one under the atm foot support.

Almost screwed up erep pass today—put in switch command to go to ZLV then did not enter bias in the das. Time to get to attitude starts over which the das bias maneuver is entered and when have Hank reminded me from the ground I had not enter — I did—& immediately knew I should not have — Owen and Jack were up there in a minute to say I should not have. We ask the ground for a new maneuver time to still get there and they quickly gave us 18 minutes where I entered and turned out okay, although we were one minute late to local vertical attitude. This is where I believe all our training paid off— a foolish mistake but we caught it and recovered to make it go—got three sites and then could not get a volcano in because of the overcast clouds.

Owen called me up to the atm and then took my picture with this Polaroid, out came a picture of a naked gal with big boobs. He took some others, turns out they were put there by Paul Patterson prior to launch. Owen said he said he was going to call Houston and going to tell Paul, but I said – careful, do not pique the curiosity of the newsmen because they will want to know what’s up and the world has a few little old ladies that do not want pin up pictures in a U. S. space station.

Owen was discouraged today—the experiment

Jack mentioned there was only one requirement for peeing in og, and that was keeping your pecker in the cup — Owen allowed, well, he found that he could minimize the urine drop at the end by being aware that the bladder was near empty then really press and increase the stream’s speed, only a small drop remains.

224

Had a thriller, was writing in my book when caution tone then warning tone came on—Jack on toilet—Owen and I soared up and found cluster ATT

warning lt and Acs (attitude control system light) on. We looked at atm panel and found much tacs firing and x gyro single, y gyro okay, z gyro single. A quick look at the ATT power showed multiple tacs firings. Both Owen and I were excited, it had been some time since we practiced these failures, plus we are in a complicated rate gyro configuration—we both really were looking at all things at once—das commands, status words, RT gyro talk backs, momentum and cmg wheel position readouts. We elected to go ATT hold but tacs kept firing, so we then turned off the tacs, looked at each rate gyro and set the best of one set back on the line. We would have gone to the csm but with our quad problems that would be a last resort. No, we had to solve it right then. We put the rate gyros back into configuration then enabled tacs, then did a nominal momentum cage—this seemed to make the system happy—namely tacs quit firing. Owen and I had settled down by then and were solving the problem again and again to insure we have not forgotten any step. We came into daylight—were two degrees or so in x and Y off so went to S. I.—maneuvered too slow so we set in a five sec maneuver time and selected S. I. again—Houston came up and I gave them a brief rundown—Owen, never giving up atm time, started my run for me while I went down for dessert of peaches and ice cream.

erep passed today, Jack got four targets, we then had an erep cal pass taking specific data on the full moon—all three of us working well together, we have trained a long time for this chance and we want to make the most of it.

Jack made a suggestion to walk on the ceiling as the floor for a few minutes —we did and in less than a minute it seemed like the floor although covered with lights, wiring runs and traps it seemed like a new place — cluttered but nice—the bicycle hung overhead was different as was the wardroom table but many lockers and stowage spaces were much easier to see and reach—I might use this technique to advantage when hunting a missing item or looking in a lower drawer.

Had to ask Capcom, Story Musgrave, to give us more work today and also tomorrow—we are getting in the swing—when you’re hot, you’re hot. We will have about 45 more days to do all the things we were trained to do for the last 2 У2—3 years—time is going fast and we must make the most use of it. Much of what we learned will have no application after Skylab—such as how to operate specific experiments, systems, where things are stored, experiment protocol, how to operate the atm, erep, etc.

225

Had bad experience today, sneezed while urinating—bad on Earth—disaster up here.

Did 10-15 minutes on dome lockers. Handsprings, dives, twists, can do things that no one on Earth can do—fantastic fun and I guess good limbering up exercises for riding the bike.

I went up and looked out of the mda windows that face the sun, but at night. What an incredible sight, a full moon, Paris, Luxembourg, Prague, Bern, Milan, Turin all visible and beautiful wheels of light and sweeping under the white crossed solar panel of the atm. Normally you cannot look out these windows because the sun glare, I could not watch Jack and Owen on their eva. Now we are in the Bay of Bengal. In just 16 minutes we swept over Europe and Eastern Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and finally over India. Too cloudy to see Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Sumatra and Java will be here soon. We repeat our ground track every 5 days but 5 days from now as we go over the same point of ground the local time there changes so that in 60 days we will have seen all points between 50N and 50s at 12 different times of the day and night. At least once we can watch Parisians (Paris residents) getting up having breakfast —

It’s not so much that we are 270 miles up in space that isolates us from the rest of the world it’s that we are going so fast. To come home we must most of all slow down, not too much or we would come in too steeply and aerodynamic forces would be too great. And not too shallow for the upper atmosphere is tenuous and might not slow you enough and you would enter off target and there is a lot of ocean.

Owen and I spent his first night in 17 days just looking out the window during a night pass. We came over France then down over Turkey, the Dardanelles were visible, then he pointed out the Dead Sea, the Sea of Galilee—I said I had been as high as anyone on Earth and had been to the lowest point on Earth, the Dead Sea last year. Owen talked of the night air glow — the fine white layer about a pencils width along the surface of the Earth.

We had looked last night for Perseid meteor shower with them burning up below us. Did not see any doing SO19 — funny to hit the atmosphere and make a shooting star, they all flying past us—with no meteoroid shield anymore, hope we do not contact any one.

Flew 509 today, disappointing because took too long to go anywhere, just jumping and diving more fun—strange we did not realize that prior to flight during training. Kicked up much dust and items that we had not seen for weeks-M092 subject cue card showed up, thank God because we needed it.

Went to bed wondering if we would have a master caution warning with the rate gyros but maybe the computer patch for course gains will work—we can’t point as accurately but we should have less disagreement between gyros.

22 6

Fixed my sleeping bag today, safety pinned at two top blankets and took up slack in blankets—too much volume of air to warm at night. Have been waking chilly about i to 2 hours prior to 6 o’clock (normal wake up time) Houston time and having difficulty going back to sleep. Maybe this will help, sleeping upside down has helped, the cooler ows as a result of the twin pole sun shade deployment is perhaps the greatest contributor.

Normal morning sequence is wake up call from Houston, I get up fast, take down water gun reading, then put on shirt and shorts for weighing in the bmmd. Take book up and weigh while Jack gets teleprinter pads and Owen reads prd. I weigh, Owen weighs, then Jack. I fix breakfast after dressing, with Owen a little behind. Jack cleans up, shaves, does urine and fixes bag and sample for three of us, I finish eating as Jack comes in and I then clean, shave and sample urine, I’m off to work at first job as Owen goes to the waste compartment. Jack is eating and about 30 minutes later we all are at work.

A sudden realization hit me this afternoon—there is no more work for us to do—atm is about it. Except for more medical or more student experiments what a sad state of affairs with this space station up here and not enough work to do — with S020, T025, SO73 gone there just isn’t much left.

We could think up some good TV productions getting 5000 watt/min of exercise per day and that should be enough.

Boy oh boy have I been farting today. You must learn to handle much gas up here and I wondered if we would forget when we went home. Owen said can’t you just see Jack in his living room with all his family and friends around and he forgets.

Funny you want a flight so badly you work hard when you get it you can’t wait to launch but once you are in orbit you’re still thinking of entry. Doesn’t make sense when examined closely. We are on the world’s greatest adventure, experience, sight seeing and it’s that desire to get home before something breaks mechanical thing do you know.

I am so glad that Owen and Jack and I are on the same crew. Our personalities fit one another well—Jack always working, always positive, always happy—Owen always serious, well may be not always.

Owen looks funny lately as he has not trimmed his mustache hair. Shaved under his neck too well—our little windup shaver and the poor bathroom light being the problem. I don’t look too great either, my hair getting long, wonder if “O” or Jack will cut it on our day off.

Talking with Sue on phone vhe through Canary Islands and Madrid—she wanted me to call her in London and Zurich somehow and gave us the number. These calls are great, best entertainment—last one I had was on s-band and it was a bomb. Only talked last 3—4 min. Sue getting ready for school and for London trip. [?] in Las Vegas and in Los Angeles. Home sounds close but it’s still 6 weeks away. Lots of living to do till then, lots to see, lots to accomplish. Amy sounded sweet. I love her more than my heart can understand.

I look forward to Jack and Owen’s calls home too because it is a way of getting news without the censoring influence of open communication.

Took the crew pictures tonight—they will look like mug shots when we get home. Should have taken them earlier for a better comparison with later in the flight.

Our tape recorders are great entertainment but continually need drive wheel cleaning. Like mine best when peddling the ergometer.

Owen got his ego bent last night. He had been commenting about weight loss, wanting more food, and salt—peanuts a favorite, Dr. Paul Buchanan called on his weekly conference and told Owen, Jack and I we’re doing okay but he needed to have a chat with him (Owen). Paul said, Owen we have been looking at your exercise data (over the last two days) and don’t think you are doing enough, maybe your heart isn’t in it—Owen about flipped because he takes great pride in his physical program, pound for pound he does more than Jack and I. He could hardly hold back, afterward he worked out till sweat was all over his body then called on the recorder to tell Paul and those other doctors the facts of the matter. Maddest I’ve seen him in months.

227

We have been trying to get the flt planning changed. I especially have had a lot of free time, Owen and Jack to a lesser degree. Jack keeps on the move all the time, so my suggestion of cutting down some was okay. Owen thought otherwise, he has a long list of useful work that he brought along, things that other scientists have suggested, worthwhile. How do I accomplish this feat of us producing our maximum without infringing on Owen’s time. He deserves some amount per day to do with as he chooses.

In a way space flight is rewarding but on a day to day it is awfully frustrating. Up here we are manipulating thousands of switches, controls, dials, etc. to accomplish some precise tasks/experiment and so with all the actions you make many mistakes, more than you would like to—each session on an experiment I say this time I will do it perfectly, but 90% of the time not so, it’s a difficult assignment. Some miscues do not mean a thing, some ruin experiment data. Hopefully none ruin an experiment. It’s hard to stay up for all these experiments day after day, but that is one of the challenges that is a real part of the job. Jack today spent whole night pass taking star/moon and star/horizon sightings on his own time to satisfy an experiment. When the pass was over, 20 marks made, he was debriefing and as he was talking he said, well, I did those sightings with the clear window protector still on. He had not noticed it in the dark. The data would be off.001 arc sec or so and that just didn’t suit Jack. He told the experimenter on record that he would repeat them later.

Food stains get all over. Not yours so much but your crewmates’ food gets on you—shirt, face, hair, you don’t know it but at the end of the day your shirt has little spots where orange juice flew over, or steak juice. Once it starts to move it doesn’t hit the floor, it keeps going in its initial direction till it contacts something or someone. You tend to shield yourself when you open your own food so the spray heads toward your crew mates who are not watching.

Teleprinter message: To Bean, Garriott and Lousma

We have been watching and listening as the three of you live and work in space. Your performance has been outstanding and the observations that you are making are of tremendous importance. Through your efforts Skylab 3 is a great mission.

Keep up the good work.

Signed,

Jim Fletcher George Low

Received this today. Why do they not send something similar when you are not doing too well, like days 2—4, we appreciated this but just wondering not only them but about myself.

Went to bed on time, do not feel as energetic as usual so feel something was coming on. Sleep is the best thing to repair me, it always works on Earth.

228

Good day today, first part anyway. One hour after wake up had an atm pass. This was the first of our new schedule. We are taking good atm pics and lots of them. We must be ahead of our nominal mission plan, I hope so. I have not felt good the last day or two. Think it’s my low water intake, I had hoped nature would take its course, but it did not. Better start forced drinking.

Failed my lbnp — had to cut off at 1 min 2 sec to go of a 15 min run. I was at 50mm and started to feel tingley—bp dropped and my heart rate started down, it took a while (5 min) to feel normal again. Pulse got as low as 47—don’t think I’ll go that far down again. This is not like Earth in that you cannot put your head low and gravity force the blood from your head and heart from your legs — it could get a bit sticky if your heart beat got too low.

Jack was observer for the run and hated to put the results on the recorder I could tell, I had to remind him—he has a fine heart. Jack opened up the 2nd tape recorder and it also had a failed drive motor belt. Two failure of a complicated expensive recorder because of a plastic circular belt one-half inch wide and 3 inches long.

Performed T013 today, went well, all equipment worked. Hope the engineers can use the data to design control systems for future space stations and there is a need to know just how man moves the station because many experiments have delicate pointing requirements and the control system must maintain this accurately pointed during manned occupation. We had wondered if it would be difficult back in training to bounce back and forth between the force measuring panels but it was not. Hand-to-hand, feet-to – hand, hand-to-feet, all were simple. Jack feels a bit 2nd level, because for the last few days with 509 and T013 he has observed and reported me, rather than do it himself.

We received a “heads down” report down from our Dr.—it means don’t look out the windows at certain times because of possible nuclear explo – sions—this time it was near the French testing sites near Tahiti—French

Polynesia. When we awoke there was a teleprinter message for three consecutive days.

229

Just found out our day off was tomorrow— Boy, the week goes fast as I honestly thought it was 2 days off.

Jack made a boo boo today. (I was flying M509 suited, boy did the umbilical give problems, especially on the rate gyro and ними modes—initially the thruster impingement on the suit caused big disturbances.) I mentioned to Houston (Dick Truly) how the back pack seemed to be too far back and the hand controller seemed too short—he came back and asked if we had taken the back spacer out—I looked at Jack and he looked at me. If they asked us later, we were going to say we flew it both ways — we made sure we could say so by flying it for 2 min with the back spacer out.

You soon find out not to set items down free without a tie down strap or spring or in a crevice or in your pocket. Even if released with zero velocity, the air currents will soon take it away, and which way is anyone’s guess. If the object is too big to tie down for just a minute you release it carefully and visually check it every 10 secs—after 2 or 3 checks you will have to reposition it like you put it originally. It’s a habit easy to break but when you do, it then can result in many minutes of lost time hunting.

Owen and I stayed up and looked at the night pass over Mexico, Houston, New York, Nova Scotia and then Paris, the Mediterranean and east Africa. We looked so big and strong and steady as we glided over the Atlantic in 15 minutes. Our atm solar panels were reflecting in the light of the near full moon behind us. We did not see Paris because of early morning haze but could Sardinia, Greece, Crete, Turkey, Israel, the Galilee, the Dead Sea and Africa where Montgomery and Rommel—Bet they would have given anything for a manned satellite to provide observation of the others troops and armor movements.

Owen became excited over the northern U. S. as he looked out and saw some aurora — this was a stranger yellower than the fog bank like aurora the other night but spectacular. There were vertical shafts of light almost like close spaced yellow green search lights.

230

Our first real day off. Best news was in the morning science report where it said we would catch up with all our atm science as well as the corollary except for medical which was reduced by 25 hours the first half of the mission, we would do the rest—I called and discussed the additional blood work, hematology and urine analysis (specific gravity) that Owen had been doing and wanting them to count that.

We did housekeeping a bunch and had to plan two TV spectaculars. Since we have atm all day we had to schedule it in the 30 min night time crew eat (first night pass for 487). Hair cut next, then acrobatics, then shower. Lots of planning for 3 ten min shows but think the folks in the old U. S.A. will enjoy.

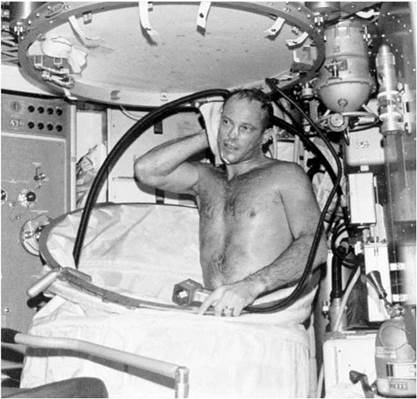

17,112.8 mph is our orbital speed. Had used 18,000 mph on TV and wanted to be sure — (look at TV tapes for details of what we did) it’s fun but time consuming to do the TV. Just as we were to finish the shower scene my phone call to Sue came in—so Jack got out and waited—when I got back in 10 min or so he undressed and got in and lathered up — we took the TV scene, he rinsed off, we then took the last shot—the one where he floats out of the shower with his shorts on. Owen came back down in a minute and told us the TV switch was in atm so we did not get it—back in the shower Jack went and we ran again—but before he could completely dry his call came in so as he dried I ran up and configured the comm in the csm for him and talked to Gratia—when she heard what was holding Jack she laughed and said “you photograph him in the strangest places.” How can we make him famous if we don’t do it a little different. Anyway we finally got it done—I did more work on the day off than a normal work day. It was late but I peddled 5004 watt/min and took my first shower.

It was cooler than I like it—the biggest surprise was how the water clung to my body — a little like Jello in that it doesn’t want to shake off. It built up around the eyes, in the nose and mouth (the crevices) and it gave a slight feeling of trying to breathe underwater—I would shake my head violently and the water would drop away (not down but in all directions) some to cling to other parts of my body, some to the shower curtain, some sort of distended the water where they were and snapped back. The soap on the face stayed and diluted with rinse water. Tasted sour when I opened my mouth—that little vacuum has sufficient pull but is rigid and will not conform to the body—so does not do too well there but okay on the inside walls, floor and ceiling. Jack had said it was better to slide my hands over the body and to scrape the water off and over to the shower wall. This worked for hair, arms, legs, but difficult for body especially back—two towels were required to dry off because water did not drain.

Owen was a little annoyed with the TV effort. He did not want to practice the acrobatics for the second time. He usually gets over it in an hour or so. It’s part of our job and we should give it equal time.

231

Flew T 20 for the first time. Jack as usual had the dirty work but was trying harder because of his error yesterday. The work was slow and tedious because it was the first time around and because the strap design was poor—the whole thing was.

Jack said “I’ve done some pretty dumb things in my life but I never got killed doing it—in this business that is saying a lot” —

Owen said “Well the dumbest thing I can remember was flying out to the observatory near Holleman nm — short hop so I decided to do it at 18,000 ft—as I neared there I started letting down, called approach control-we talked and as I descended their communications faded out—I kept thinking why should they fade out—it suddenly dawned, shielded behind mountains — full power and a rapid climb in the dark saved my ass—I think of that incident several times every month over the last three years.”

Jack was saying that when we got back he and Owen might be considered regular astronauts—Owen laughed—it was beyond his wildest dreams to be classed as a real astronaut.

Been wishing Owen and I had taken pictures of the Israel area the first time we stayed awake to see it—I want to give pictures of this region to some of my religious friends.

Sue told me last night that Boe Adams would be indicted for borrowing twice on the same bank stock—she told me about the 37 murders in Houston —we had not heard because on our nightly news they tend to eliminate the stressful news. Putting our 5,000 watt/min on the ergometer (or is it ergrometer like some say) in one 10 min and one 20 min run—have to stop at 15 min usually and let my 185 heart rate reduce to 150 or so, then finish.

Was supposed to photograph the Antipodes Islands southeast of New Zealand but was too cloudy—Antipode is the opposite place on Earth and the opposite from the islands is on the English Channel—so the original discoverer must have been from near there—these are on the 180th meridian.

We are crossing the date line every 93 minutes so we gain a day but of course as we go east we lose it an hour every time (look up some news on Glenn’s flight, might discuss this). 24 hours, so it all averages out.

Jack’s having his ice cream and strawberries. Jack’s food shelves when we transfer a 6 day food supply are almost full of big cans plus a few small—Owen and I have half full shelves with more or less equal amounts of small and large cans—he really puts down the chow.

All are in a good mood, morale is high in spite of all the hard work, we are getting the job done.

I was supposed to take pictures of the plains of Nazca in the Andes in Peru (about 300 mi se of Lima). Criss-cross patterns are the dominant features but I could not pick out even the 37 mi by 1 mi place called the airfield of the ancient astronauts. I was supposed to photograph with the 100 mm Hasselblad and the 300 mm Nikon and identify the plains and describe the geometric pattern. Also describe the general appearance of the plains and geographic relation to the adjacent features. — All in 5 min 10 sec of viewing—weather was broken clouds and I did not see the target. Could have several days ago many times—we must change our approach to ground targets.

232

A tough tough day. Worked almost all day on trying to find the leak in the condensate vacuum system—hundreds of high torque screws, stethoscope, soap bubbles, 35 psi nitrogen, reconfiguring several pieces of 20 equipment —we never found the leak—that effort must have cost $2 Уг million in flight time.

Jack feels down, the SO19 stuck out and would not retract—we will keep using it but may have to jettison if it won’t come in. He’s hit the bed early, tired—the last atm pass of the day he ran all the S055 in mechanical reference (102 steps less than optical) when it should have been optical—he was dragging—it was partly my fault as I left it there after my last run.

Owen got the word that the citizens of Enid would be putting their lights on for him to see—I went up with him—it was the clearest, prettiest night we’ve had—we could see Ft. Worth-Dallas perfectly—a twin city, one of few — then Oklahoma City then Enid then St. Louis then Chicago—Owen made a nice narration. He said he started to say he saw Tulsa up ahead and realized it was Chicago. Paul Weitz said that was the one thing he never became accustomed to on his flight—the speed which you cover the world, especially the U. S.

Passed my mo 92 today but used saddle position 5, may be too high out of the lbnp and not pull my blood so hard—Owen and I had a laugh by saying my delta p of 50 never gets lower, I just keep getting further out of the can—we visualized late in the mission sending TV to the doctors with just my feet in the unit but still pulling 50mm.

Heard tonight we may put in the rate gyro 6 pack — I told Owen I would do it because they did the twin pole and because that sort of work fits my skills better than Owen’s—hope it did not hurt his feelings but that is the way I see it and that’s my job—Owen even brought it up by saying “I think you want to put out the 6 pack and that’s okay with me—I’m glad to do it but know you want to”—I said you’re right we don’t need this job but if it comes up we will pull it off.

233

Today was a special day — found out we were going to put in the rate gyro 6 pack—who to do it—Owen still wants to do it and so do I. Made up my mind that it would be Owen and I but after reading the procedures realized that I should stay in because of my csm experience—Owen and Jack are just not up on it and it is the best decision—Jack will do the 6 pack as he is the most mechanical—Owen does not do those things as well as Jack, it will be tough to tell him tomorrow — I was awake for about two hours trying to put the pieces together and think Owen and Jack outside—me inside is the best way.

Got SO19 in today—just decided to turn the retract crank hard—did so for 10-15 turns but the clutch slipped and it did not move. When I looked in the optics. I think turned it out (extend) then in (retract) then out then in and low and behold it came in.

I took it apart and looked okay as far as possible ice—looked as if a chain synchronizing the x screw drive was loose and may have stuck on a sprocket. I checked with Houston, adjusted a idler sprocket and it seemed to work okay. Jack looked at it too and noticed another chain that might be too tight so we loosened it. The mirror was so cold that it had condensation on it for several hours. Houston (Karl Henize) wanted it out in a vacuum so the moisture would sublimate and minimize residue deposited.

Had to laugh, Jack said he couldn’t fart in the lbnp because he was being pulled down too hard on the saddle—needs a hole in it said Owen—we all pass gas up here—the nice way to say it is “watch out for my green cloud” if someone else comes near.

234

Told Owen and Jack about eva crewman, they both seemed happy, told them what factors influenced me and who I felt most qualified for each position. Called Houston and told them later, they seemed happy. I started looking at the equipment for the job—all in good shape. Gingerly tested the tool for the interior plug removal and it looked promising. Will have to work on check lists later—need many questions answered from Houston.

Day went fast as it always does—only hard part was exercise io minutes (i min ioo watt, i min @ 125, 2 @ 150, 2 @ 175, 2 @ 200, 2 @ 225) on the ergom – eter. Then some Mk 1 and Mk 11 work—then 25 min where I increase my 1700 watt-min to 5000 watt-min. It’s a good workout and more than I did on Earth.

Owen seemed a little distant later today, don’t know whether it is the hours or the EVA.

Worked on the coolant loop leak inspection. Jack made a break through by taking out screws which we could not turn using vice grips—did not finish procedure but found no leaks either, must be outside (I hope so).

Owen reported an arch on the uv monitor in the corona yesterday. We called it Garriott waves to the ground—he was in the lbnp and was embarrassed and told us to knock it off— we were happy for him. Today he heard the ground could not it see it in their taped TV display — he went back and checked and found it to be a sort of phantom or mirror image of the bright features of the sun except reflected in the camera by the instrument. He’ll get over it (maybe that’s why he was distant).

Crippen woke us this morning with Julie London singing “The Party’s Over.” Jack wanted to make this Julie London Day, so did Crippen so he could call her but Owen won out with Gene Cagle Day.

Got my exploration map up on the wall of my bunk room—Have to write propped up on the wall since my bunk is upside down.

233

Would you believe it we get better н-alpha pictures at sunset than we do at sunrise because our velocity relative to the sun is less and that effectively changes the freq of the filter in our н-alpha cameras and telescopes—not a small item either.

Owen’s humor—I said “watch your head” as I pulled out the film drawer. Owen replied “I’ll try but my eyeballs don’t usually move that far up.”

We were laughing about the malfunctions we had after we discovered the water glycol leak — I wanted to call Houston and say “Jack is working on the cbrm mal, Owen on the camera mal—tomorrow after we fix the door mals, the 9 rate/gyro mals and the 149 mal of the nylon swatch mal, I’ll start work again on the coolant loop some more or the water glycol leak mal”.

Everyone feels better about eva—I worry too much and Jack will pull it off. Funny how easy it looks now that we are going to do it—did it get easier as we understood the plan or did we just want it to be doable? Morale is high—did perfect on my mo 92/171.

236

eva day. I was talking to myself during eva and Jack wondered what I was saying—I told him “I was just shooting the shit.” Jack quipped, “get any?—what’s the limit on those?”—Owen was saying “Come on, . . . hustle. . .” Give us some of that (positive mental attitude)—pma (he doesn’t believe in it. But knows I use it on me and them also.) “Go Earl (Earl Nightingale).” I said “you need it, it’s worked on you whether you like it or not.”

Jack had a difficult time with connector number two—it was difficult for me to keep from asking questions of Jack as I wondered if that would be the end of the show but he said don’t talk for awhile and just let me work on it. He did for a very long 5 minutes and then reported connected.

Owen was elated with the view over the Andes—the 270 degree panorama with 3 solar panels in the field of view to form a perspective or frame work they were flying over all the world outside of the vehicle going 17,000 mph (get transcript of evas). Lost three shims and one nut taking off the first ramp.

We have only 1 to 2 min of TV recorder time left so have to hold it for Owen’s return to the fas. Owen had to come out of the foot restraints to remove the ramps from the so 56 and 82 a doors. Sun end eva lights worked this time —Jack said he can see many orange lights, we were over mid Russia —not many cities—Orion came up, a beautiful constellation, Owen still working on bolts at Sun end.

Got a master alarm—cmg sat — s/c going out of attitude—I put it in att Hold—TACS when was out 16 degrees.

Sometimes, like on a tall building, you get a controllable urge similar to jumping off which is to open a hatch to vacuum—or take off a glove or pop a helmet—fortunately these are passing impulses that you can control but it is interesting to know they take place.

Great eva today — all happy tonight. Owen summed it up when he said “It’s something that needed doing.” Jack said he thought I made the right decision—so do I and we are all satisfied.

Owen bitched about the medical types that take care of our food because they told Paul Buchanan our food cue card were wrong for optimal salt and they had not bothered to update and had been making them up with supplements. — Owen flew off the handle because he has been needing salt.

It is comforting to know someone (many someones) on the ground are working your space craft problems faster and much better than we. We generally perform a holding action if we can. Till help and advice comes, then take the info or suggestions and do them, this is the only way you can free your mind to do the day to day tasks, the productive tasks while someone is trouble shooting your problems.

Heard yesterday that Fred Haise crashed in a Confederate Air Force T-6 and was badly burned but would survive. Seemed his engine out and he dead sticked it into a field, a wing tore off and the whole thing caught fire—burned him over his whole body except his face, so that’s lucky—heard today that he was on oral foods so he must be improving.

Rearranged my bunk room—put a portable light on the floor near the head of my bed and turned my beta book bag upside down so I could grab the items inside easier. I use the door of the bottom locker (pulled out about 30 degrees) as a writing desk. Stole the power cable for the light from the spiders’ cage—hope Owen doesn’t get upset. He has been getting messages to feed them both filet and keep them watered. Will we bring them to the post flight press conference?

The teleprinter is a device about which you can have mixed feelings — it would be hell to get the information any other way so it must be cared for as an expenditure of effort. But at the same time every time you hear it printing you know it’s more work for you to do. Wish we would get a non work related message sometime.

237

Felt good to have atm film again. Operating the atm telescopes and cameras is one of the most enjoyable tasks here. It is challenging, you can directly contribute to improved data acquisition—Owen has effectively changed the method of operating it in just % of a month. The Polaroid camera and the persistent image scope have made a significant difference.

I had Houston give all the atm passes tomorrow, our day off, to Jack and I, so Owen could finish some things he is behind on and do some additional items that he has planned prior to flight—the flight is Уг over and he has little spare time—he needs some to be happy.

Using the head for sponge baths (bad name because sponges squirt water out when pushed on the skin).

(Tell story of mdac test) has become more pleasant as I have been less careful about sprinkling water about. I tend to now splash it somewhat. And after the bath is complete wipe up the droplets on the walls. None on the floor like on Earth if you did the same.

We passed Pete, Joe and Paul’s old space flight mark, in fact we now hold the world record for space flight—it feels good to be breaking new ground said Jack today. We will be Уг into our mission tomorrow night.

Our TV got too hot during eva and quit working—we will do the rest of the mission on one TV I guess. Funny, they did not insulate it sufficiently. We had a plan to put it out the solar air lock for eva but can’t do it now.

Sue and Amy will be getting up soon over in London—we do not go over London, it above 50 degrees N latitude.

Europe is an awfully small part of the Earth—so is the U. S.. Jack has mentioned several times that each time he looks out the window it’s either water or clouds or night.

The odds for man all beginning long ago back in the sea is reasonable just from a total volume of water available to total area of land available.

Jack has a small sty on his left eye, he wanted some “yellow mercury” but settled for Neosporin. Jack treated himself but Owen will examine it tomorrow — Paul Buchanan said for us to be extremely careful because that could be contagious. Perhaps a streptococcus of some type.

Our little Sony tape recorders are holding up so so. It is necessary to clean the rubber drive wheel about once per two days—lots of trouble.

Did Mk I exerciser TV today, also some Mk 11 and side horse swinging on the portable hand grips.

I keep my personal items in a locker above my head—it was across from me at eye height till I turned my bunk up side down, it has a hand hold with a thin rubber sheet covering it. The rubber sheet has a horizontal slit in it and serves to keep objects inside when my hand is inside searching for one of the 20 or so objects within. As I look inside I see chewing gum, stereo tapes,

Skylab sticker, my dental bridge, a string tether for books. Some tape drive wheel cleaning swabs, a couple of old teleprinter messages.

238

We are going to sleep just under one hour to the mission midpoint. Our science briefing today showed that we had made up the atm observing time we missed early in the mission and predictions are for us to exceed even the 260 hr atm sun viewing goal. We are ahead in corollary experiments. They are even having us try a new so 63 using the ams that was not to have been till sl 4.

Took my second shower, noticed that you could not hear much of the time less you shook your head because large amounts of water cling to your ear openings. I was the only one showering today.

We did urine refractory tests to determine specific gravity.

Exercised today although that is not my plan for day offs—not doing the exercise would be a nice reward but did not have time eva day.

Think the reason the days pass so quickly up here is the variety of tasks we each do—we never do any one thing longer than 3 hours and the typical would be one hr or less — and you feel you’re doing what you trained for for more than 2 Уг years. I spent much training time in the Navy for war and never went, thank God.

Talked to my mom and dad. Mom is so happy with Pepper and David’s new baby, Brandi Frances, that she doesn’t know what to do — if it had been a boy they were going to make the middle name Arnold. That might suggest Pepper’s feelings toward her grandparents. Mom said Clay was leaving for school next week—had returned from California at 3 in the morning.

Am going thru all my music tapes to grade them pop or easy listening. And very good, good or so so. Seems I listen to the same 3 or 4 all the time.

Jack made an excellent observation when he said NASA should play down the spider after the initial release because it tended to detract from the more meaningful experiments we are doing up here. Will the tax payer say, now that I know what they are doing up there, I don’t like my money going for that sort of thing.

Owen tried to do a science bubble experiment with cherry drink but didn’t look too promising to me. He kept losing the drop of drink from the straw.

Jack suggested we put a pair of trousers in with our clothes in the csm so we would have a full uniform on the ship — we will wear our hypertensive garment for entry—in fact we may wear it for the sps burn since we found out Paul and Joe had a gray out during this burn.

We may want to give the entry guidance to the cm early if gray out occurs there too.

I have noticed if I do not force myself to drink then I will drink much less than on Earth and will dehydrate—I do not seem to automatically desire the proper quantity of water. Owen and I were talking about a possible advantage to the 18 days post flight urine and water measuring period—I suggested that when we get back we may not naturally readapt to one G and become dehydrated there. He does not agree at all.

Jack is playing his music in bed. Owen and I both agree on his music at least.

I slept 9 hours last night, a record for me in space.

239

Spent part of the morning composing a message to the dedication of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Space Center. Thanks to Owen’s and Jack’s suggestions, it turned out acceptable I think. It must have because Dr. Fletcher read only President Nixon’s and ours.

When I used to go from compartment to compartment I would be lost when I got there—now I look ahead as I enter and do a quick roll to the “heads up” attitude for the space I’m entering.

Owen said his only regret was that he would never adapt to Zero G again—he thinks Pete is the only one besides ourselves that has ever done so — the weight loss and the poor appetite are the evidence. We could gain all sorts of weight if we wished.

My pockets are most useful—Lower left—all trash I pick up I empty from time to time. Jack just keeps it there till he throws the pants away. Right lower, tape and tools if needed. Upper left, timer and tools. Upper right sizzers and flashlight. The little pockets for pens and pencils, knife and sizzers. Far from perfect—flaps too short, needs snap & need more width.

I’ve noticed I enjoy the atm time—The controls are an intellectual challenge and just interesting. Mostly I think it’s because it’s the only solitude that is available. No noise from anyone else—It’s a time to be alone. In the sleep compartment someone is right next to you & it is not so private somehow —Here, seldom does anyone float by.

By the way, living in og means you make no noise generally as you approach someone else, no footsteps, no ripples in the water, just silent swift movement. I’ve noticed that each of us tends to say something to another as we approach just to keep from surprising him—startling him. I noticed this silent movement first in skin diving — I could look around and suddenly there some 3—5 feet away would be a big fish—It all depended on the visibility of the water because much of the time one kept a good scan going.

The sty on Jack’s left eye is going away — He found no “yellow mercury” but used Neosporin.

This message was sent to the ground by Alan for the dedication of lbj Center.

Owen, Jack and I would like to send our best wishes to Mrs. Johnson, Governor Brisco, Dr. Fletcher, Dr. Kraft and all the other distinguished guests and officials at the dedication ofthe Lyndon Baines Johnson Space Center. The work in which we are engaged now in Skylab would not be possible had it not been for the strong support and leadership of Pres. Johnson in the Senate and the Presidency.

Our present preeminence in space is in no small way a result of his grasp ofthe fact that a progressive program of space exploration contributes significantly to the future well being of our nation and its people. We are proud to be representing nasa and the Lyndon Baines Johnson Space Center as we circle the Earth.

We believe the work we do here now is an extension of that which he chartered and championed.

240

So I feel on top of the world.

Ergometer broke, I fixed it then went back and overtorqued it (should have stopped at 30 in lb) and broke the bolt. Jack used the bone saw then his Swiss Army knife (wonder if the Swiss army really uses them) hack saw blade to fix it—I pedaled 6007 watt/min with 3 min at 300 watts. A new record both for time & for max power. We are whipping into good condition.

I got mad at Owen today — He has a habit of acting disgusted when I make a mistake—Today I had aligned the atm wrong and he was nodding his head—I lost my temper and told him to quit. Maybe he will take the hint.

I asked the ground to let Owen fly M509 soon—He has not flown any simulator, it is safe & it would answer some important questions. Hope Jack won’t mind.

Also asked the ground to invent a pointing device for locating ground sites we should photograph rather than just telling us which window—Hope they will because it would help. Most of the flyover time is spent verifying that you have the right place by looking at the maps, that other observations are compromised.

They wanted to know tonight if Owen would fly on our day off and I said sure—later I asked him and he said ok.

Did a TV tour with Jack today. He was shifting his eyes a lot at first and I told him—he never did so again, he likes TV and will be very good at it when we return. I try to teach them all I know—or think I know.

About every other night I get up because of unusual noises — mostly they are all thermal noises. The most unusual view occurred once as I left my bunk and peered up to the forward compartment. The Уг light from the lock revealed three white suited figures, arms outstretched, leaning several awkward ways—silent, large with white helmet stowed over them—one drying, the others waiting to dry. I was shook a little by the eerie sight so I went to the wardroom and looked out. The dark with white airglow layer and white clouds filed the lower right portion of the window like it was one foot away. It startled me even more.

241

Morale is high—work level is high. Last night after dinner Owen asked Jack if he (Jack) would like him (Owen) to take his late atm pass. Jack said no he was looking forward to it—he wanted to find some more Ellerman bombs—(bright points in penumbra near sun spots) as he got some earlier —I interrupted and mentioned that the flight planners had voice uplinked a change in the morning, assigning me to the pass. Owen laughed—here we all are fighting for the last atm pass.

Kidded Owen about wearing his M133 cap—said Jack and I better watch our ps & Qs tomorrow, Owen will be in a bad, criticizing mood—he took the kidding well, hope it will have effect.

I have been decreasing my number of mistakes significantly by only doing one job at once —atm is the one most enticing to doing special task as a set of instruments is operating. Invariably if I do, I do not get back in time or do not catch a simple error in the set up. I am waiting now doing SO19 which requires little thought other than checking the exposure time every few seconds. Exposures are 270, 90 or 30 sec.

242