SETBACK AND RECOVERY

On 26 August 1966 the command module of CSM-012 arrived at the Cape in a container prominently labelled ‘Apollo One’.

North American Aviation was to have shipped it several weeks earlier, but the failure of a glycol pump in the environmental control system had led to the exchange of this unit with its CSM-014 counterpart. Although the customer acceptance review identified other ‘‘eleventh-hour problems’’ associated with the environmental control system, NASA had taken receipt.

The Office of Manned Space Flight held the AS-204 design certification review on 7 October, and declared that the launch vehicle and the spacecraft ‘‘conformed to design requirements’’ and would be flightworthy once a number of deficiencies had been overcome. Sam Phillips issued a list of these deficiencies to Lee B. James at the Marshall Space Flight Center, Joseph Shea at the Manned Spacecraft Center, and John G. Shinkle, Apollo Program Manager at the Kennedy Space Center, requiring speedy compliance. On 11 October Phillips was informed by Carroll Bolender of a report he had received the previous day from Shinkle detailing increasing delays in the preparation of CSM-012. When the spacecraft was delivered, 164 ‘engineering orders’ had been identified as ‘open work’ – despite the fact that the accompanying data package had listed only 126 such items. By 24 September the list had grown to 377, and Shinkle ventured that about 150 of the 213 additional orders ought to have been identifiable by the manufacturer prior to the customer acceptance review. The issues included the environmental control system (which had failed again), problems with the reaction control system, a leak in the service propulsion system, and even design deficiencies with the couches that had obliged the company to send engineers to the Cape. On 12 October Phillips wrote to Mark E. Bradley, Vice President of the Garrett Group, whose AiResearch Division had supplied the environmental control system under subcontract to North American Aviation, explaining that its reliability threatened a “major delay” to the AS-204 mission. To Phillips, the problems seemed “to lie in two categories: those arising from inadequate development testing, and those related to poor workmanship”. A replacement was delivered on 2 November, and testing resumed as soon as it was in place. However, the unit malfunctioned and had to be returned to the company.

On 25 October the propellant tanks of the service module for CSM-017, assigned to AS-501, failed catastrophically in a test at North American Aviation. The normal operating pressure was 175 psi, but it had failed after 100 minutes at the maximum requirement of 240 psi. The test had been ordered following the discovery of cracks in the tanks of CSM-101, assigned to AS-207. The failure was particularly puzzling because the tanks of CSM-017 had been subjected to 320 psi for several minutes in ‘proof testing’. ASPO set up an investigation, which was to report by 4 November. As SM-012 had been through the same test regime, Shea grounded it pending this report. The problem was determined to be stress corrosion in the titanium resulting from the use of methyl alcohol as a test liquid. The point of the test was to verify the integrity of the tanks, and because the hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants were toxic another fluid had been used – and unfortunately this had caused damage! The remedy was to switch to a fluid that was compatible with titanium, and it was decided to use freon in the oxidiser tank and isopropyl alcohol in the fuel tank, with the additional stipulations that the systems must not have been previously exposed to the actual propellants and that after the tests the system must be purged by gaseous nitrogen. With the issue resolved, the tanks of SM-012 were removed for inspection and confirmed to be free of cracks.

The crew for the CSM-014 mission was announced on 29 September 1966. Wally Schirra would be in command, flying with Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham. They would be backed up by Frank Borman, Tom Stafford and Michael Collins. Schirra was the only experienced man of the prime crew, but all the backup astronauts were veterans. In fact, Deke Slayton had given Schirra and Borman these assignments in March, on their return from an international ‘goodwill tour’ after the rendezvous of Gemini 6/7. Stafford and Collins had been assigned following Gemini 9 in June and Gemini 10 in July, respectively. Slayton had actually earmarked the rookies Eisele and Chaffee to Grissom’s crew, but in late 1965 Eisele had injured his shoulder in weightlessness training in a KC-135 aircraft and dropped out of training, prompting Slayton to swap Eisele with Ed White, whom Slayton had earmarked for Schirra’s crew. This Apollo 2 mission was to be a straightforward rerun of Apollo 1 to further evaluate the spacecraft’s systems.

In early December 1966, accepting that Apollo 1 would not fly that year, George Mueller postponed it to February 1967 and also deleted the Block f reflight in order to prevent the slippage of CSM-012 from impacting the Block II missions scheduled for later in 1967. Schirra had hoped to put his crew first in line for the dual mission, but Slayton imposed a rule that the man who would operate the CSM alone while his colleagues flew the LM must be experienced in rendezvous, since if the LM were to become crippled he would have to perform a rescue. Eisele was a rookie but Scott had performed a rendezvous on Gemini 8, so Slayton exchanged Schirra’s crew with McDivitt’s crew. Schirra was not pleased at being given the backup role, but Slayton had always intended to assign McDivitt the dual mission.

On the new schedule, AS-206 would launch LM-1 for an unmanned test as soon as possible after Apollo 1, and if this was satisfactory McDivitt’s crew would fly the dual mission (which was now AS-205/208 because deleting CSM-014 had released AS-205) as the revised Apollo 2 in August. This revision was publicly announced on 22 December, together with the assignment of Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan to backup McDivitt’s crew. Also, if two unmanned tests proved sufficient to ‘man rate’ the Saturn V, the intention was to launch AS-503 with a CSM and LM. The crew for this mission would be Frank Borman, Michael Collins and Bill Anders, backed up by Pete Conrad, Dick Gordon and Clifton Williams. These assignments had been made after Young flew Gemini 10 in July, Conrad and Gordon flew Gemini 11 in September, and Cernan backed up Gemini 12 in November.

The Gemini missions had demonstrated that for an astronaut on a spacewalk to be able to work effectively he must be provided with mobility and stability aids. On 6 December 1966 Slayton warned Joseph Shea that without handholds and tethering points, a transfer from the forward hatch of the LM to the CSM’s hatch would not be feasible. On 26 December Slayton recommended that a spacewalk be scheduled 100 hours into AS-503, after the two firings of the LM’s descent propulsion system but prior to the descent stage being jettisoned. One of the two astronauts would egress from the forward hatch and stand on the ‘front porch’ to assess the environmental control system in the LM during depressurisation, using the hatch, the performance of the life-support backpack, and the egress procedure for the emergency transfer. In addition, whilst outside, the spacewalker was to photograph the exterior of the LM to verify that it had not been damaged during its retrieval from the S-IVB. He would then re-enter the LM and the cabin repressurisation system would be tested, simulating the end of a moonwalk.

On 26 January 1967 Schirra’s crew made a ‘full up’ systems test of CSM-012 on its AS-204 launch vehicle. But the spacecraft drew its power from the pad, and the capsule was not pressurised with pure oxygen. It had not been a very productive day. ‘‘Frankly, Gus,’’ Schirra said in the debriefing with Grissom and Shea, ‘‘I don’t like it. You’re going to be in there with full oxygen tomorrow, and if you have the same feeling I do, I suggest you get out.’’ But there was a determination to catch up on the several-times-delayed schedule.

The next day, Friday, 27 January, Grissom’s crew attempted the ‘plugs out’ test in which the spacecraft would be on internal power and pressurised with pure oxygen at 16 psi (i. e. slightly above ambient) for an integrity check. If successful, this would clear the spacecraft for flight. After a simulated countdown, they were to end the day with an emergency egress drill.

In Houston, Flight Director John Hodge was monitoring progress, but the action was at the Cape. Slayton was in the Pad 34 blockhouse talking to Director of Launch Operations, Rocco Petrone. Also present was Stu Roosa, a rookie astronaut serving as the primary communications link with the crew. The Spacecraft Test Conductor, Clarence ‘Skip’ Chauvin, was in the Automated Checkout Equipment facility of the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building.

‘‘Fire!!’’ yelled Grissom at 18:31 local time, in a hold at T-10 minutes. ‘‘We’ve got a fire in the cockpit.’’

In all, there were 25 technicians on Level A8 of Pad 34’s service structure, and five more either on the access arm or in the White Room. Henry Rogers, NASA’s Inspector of Quality Control, was in the elevator, ascending the service structure. Systems technician L. D. Reece was waiting for the ‘Go’ to disconnect the spacecraft for the ‘plugs out’ test, which had been delayed by problems with communications, most notably the whistle from an ‘open’ microphone that could not be located.

‘‘Get them out of there!’’ commanded Donald Babbitt, North American Aviation’s Pad Leader, on hearing Grissom’s call. Mechanical technician James Gleaves was closest, but a spout of flame burst from the capsule before he could react, and he was beaten back by the flame and smoke.

Gary Propst, a technician of the Radio Corporation of America, was on the first level of the pad monitoring a TV camera located in the White Room pointing at the window in the spacecraft’s hatch. On hearing Grissom’s call, he looked up and saw a brilliant light in the window and gloved hands moving about within.

As soon as Slayton realised what had happened, he sent medics Fred Kelly and Alan Harter to the pad. ‘‘You know what I’ll find,’’ Kelly observed pointedly. The best that they would be able to do would be to supervise the retrieval of the bodies. On reflection, Slayton decided to accompany them. ‘‘We were the first guys from the blockhouse to reach the pad,’’ he later pointed out. Despite the intensity of the fire, Grissom, White and Chaffee had died by asphyxiation as a result of the toxic fumes created by the incomplete combustion of the synthetic materials in the cabin. They had received second and third degree burns, but these in themselves would not have been fatal. After several minutes Slayton left the White Room to call Houston, to report the situation. Shea had just arrived back in Houston and was briefing George Low when the news came through.

The Astronaut Office in Houston was very quiet. All the ‘old hands’ were absent. With Slayton away, Don Gregory, his assistant, ran the routine Friday staffmeeting. The meeting had only just convened when the red phone on Slayton’s desk rang. Gregory answered, then reported, ‘‘There has been a fire in the spacecraft.’’ Michael Collins was the senior astronaut present. He arranged for Al Bean to track down the wives. In each case, the news had to be broken by an astronaut who was also a close friend of the family. Charles Berry and Marge Slayton went to see Betty Grissom. Pete Conrad was sent to track down Pat White. Gene Cernan would have been ideal for Martha Chaffee because they lived next door, but he was in Downey with Tom Stafford and John Young, so Collins went to give her the bad news himself.

Al Shepard was in Dallas, Texas, about to deliver a speech at a dinner. He was taken aside and told of the fire. Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham

were flying home from the Cape, and were told upon touching down at Ellington Air Force Base. Schirra immediately called Slayton at the Cape, who filled him in on the details. James Webb, Robert Seamans, Robert Gilruth, George Mueller, Kurt Debus, Sam Phillips and Wernher von Braun were at the International Club in Washington with corporate officials, including Leland Atwood of North American Aviation, to mark the transition from Gemini to Apollo. Webb immediately ordered Seamans and Phillips to the Cape to investigate. As Webb observed to newsmen shortly thereafter, “Although everyone realised that some day space pilots would die, who would have thought the first tragedy would be on the ground?”

The Board of Inquiry was chaired by Floyd L. Thompson, Director of the Langley Research Center, with Frank Borman as the Astronaut Office’s representative. The origin of the fire was near the foot of Grissom’s couch, where components of the environmental control system had repeatedly been removed and replaced in testing. Although the investigation did not identify the specific ignition source, it did find physical indications of electrical arcing in a wiring harness. ft was concluded that at some time during either manufacturing or testing an unnoticed incidental contact had scraped the insulation from a wire and thereby created the opportunity for a spark. This had ignited nearby flammable material, and in the super-pressurised pure-oxygen situation the result had been a brief but intense ‘flash’ fire. fn fact, there had been some 32 kg of nylon netting, polyurethane foam and velcro – all of it flammable in such conditions. fn retrospect, the worst flaw was the inward-opening hatch, which even under ideal conditions took several minutes to open, and would have been impossible to open with the internal pressure above ambient. Because neither the launch vehicle nor the spacecraft had been loaded with propellants, the ‘plugs out’ test had not been judged hazardous. Nevertheless, the launch escape system was directly above the spacecraft, and if the heat from the fire had ignited the solid propellant of this rocket the White Room crew would almost certainly have been killed as well.

fn an Associated Press interview in December 1966 Grissom had told Howard Benedict: ‘‘ff we die, we want people to accept it. We are in a risky business and we hope that if anything happens to us it won’t delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life.’’

fn an effort to reduce the risk of a fire during ground testing, it was decided to use an atmosphere comprising 65 per cent oxygen and 35 per cent nitrogen. After liftoff, the nitrogen would be purged and the pressure reduced to the originally planned 100 per cent oxygen at about 5 psi.

Although the investigation into the fire would take months, on 31 January NASA headquarters directed the Manned Spacecraft Center, Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center to proceed as planned with preparations for AS-501 with CSM-017 and LTA-10R, except that the command module was not to be pressurised with oxygen without specific authorisation.9 On 2 February CSM-014 was delivered

LTA-10R was a refurbished LM test article serving as a mass-model.

The exterior of the fire-damaged Apollo 1 command module in which Grissom, White and Chaffee died (top left); a view through the hatch; the crew positions, with the hatch above the center couch; the vicinity of the environmental control unit, where the ignition source is believed to have been; and its disassembled outer structures. Glenn, Cooper and Young escort Grissom’s coffin.

to the Cape to assist in training the technicians who were to disassemble CM-012 for the investigation. On 3 February George Mueller announced that although manned flights were grounded indefinitely, the unmanned AS-206, AS-501 and AS-502 were to proceed as soon as delivery of the hardware allowed. While the investigation into the fire was underway, Mueller suggested that when the Block II spacecraft became available the CSM-only flight should be deleted and the effort switched to combined testing with the LM, but Robert Gilruth warned that it would not be wise to test two new vehicles at once. In March it was decided to fly an 11-day CSM-only mission, in effect to perform Grissom’s mission with the upgraded model, and Slayton tipped off Schirra that his crew would fly it, backed up by Stafford’s crew. On 21 February, the day that Apollo 1 had been scheduled to launch, Floyd Thompson gave Mueller a preliminary briefing on the investigation’s findings, and several days later Robert Seamans sent a memo to James Webb listing Thompson’s early recommendations.10

On 15 March Deke Slayton proposed that a rendezvous with the S-IVB stage be a primary objective of Schirra’s flight, and said that this should occur “after the third period of orbital darkness’’. On 5 April Sam Phillips told the Manned Spacecraft Center, Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center that the profile for the first manned flight would be based on that developed for Grissom’s flight, dated November 1966. As the complexity of the mission was not to exceed that previously planned, and as no rendezvous had been planned, the rendezvous exercise should be assessed in terms of how it would complicate the mission rather than how it would advance the program. As the flight was to focus on evaluating the spacecraft’s systems, Chris Kraft pointed out on 18 April that if a problem were to develop that would require the cancellation of the rendezvous, then any manoeuvres which had already been made would complicate the nominal contingency de-orbit procedures. The rendezvous should not be initiated until “after a minimum of one day of orbital flight’’ and should be “limited to a simple equi-period exercise with a target carried into orbit by the spacecraft’’. On 2 June Phillips agreed with George Low that there should be a rendezvous but insisted that this should not be listed as a primary objective. The double-hatch of the Block I had been replaced on the Block II by a single ‘unified hatch’ on a hinge that swung outward. It had a manual release for either internal or external use, could be opened in 60 seconds irrespective of the differential in pressure, and was capable of being opened in order to conduct a spacewalk. But Phillips directed that there ‘‘be no additions that require major new commitments such as opening the command module hatch in space or exercising the docking subsystem’’.

NASA announced on 20 March 1967 that the unmanned LM-1 flight would be transferred from AS-206 to AS-204, which had become available. The rationale for the AS-205/208 dual mission with CSM-101 and LM-2 had been to ensure that testing of the LM would not be held up by the Saturn V development problems. The AS-501 and AS-502 development flights were to carry refurbished LM test articles, but unless

The final report of the Apollo 204 Review Board was submitted on 5 April 1967.

the pace of LM development dramatically picked up, the heavy launcher would become available ahead of the LM, thus rendering the ad hoc dual mission redundant. It was therefore decided that if the LM-1 test flight proved unsatisfactory, AS-206 would launch LM-2 unmanned to address the remaining test objectives. On 25 March George Mueller directed that missions be numbered in the order of their launch, regardless of whether they employed the Saturn IB or Saturn V and whether they were manned or unmanned – previously only the manned missions were to be counted. On the 1966 plan, Apollo 2 was to be CSM-014 (Schirra) and Apollo 3 was to be CSM-101 (McDivitt) flying the dual mission. The cancellation of the Block I reflight advanced CSM-101 to Apollo 2. After the fire, the desire not to reassign the name Apollo 1 had resulted in CSM-101 (Schirra) being seen as Apollo 2. But with paperwork in circulation for a variety of mission plans numbered up to Apollo 3, Mueller precluded the possibility of administrative confusion by directing that the first scheduled mission, AS-501, be named Apollo 4.[47]

On 7 April 1967 Joseph Shea was transferred to Washington as Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, and Low succeeded him as ASPO Manager at the Manned Spacecraft Center. Several days later, Everett Christensen resigned as Director of Mission Operations at headquarters.

A joint meeting of the Manned Spacecraft Center’s Flight Operations Directorate and Mission Operations Division announced on 17 April that: (1) successful firings by the descent and ascent stages of an unmanned LM, including a ‘fire in the hole’ separation of the two stages, should be prerequisites to a manned LM being allotted these functions; (2) a demonstration of EVA transfer should not be a prerequisite to manned independent flight of the LM; (3) the Saturn V should be ‘man rated’ as rapidly as possible; (4) three manned Earth orbit flights involving both the CSM and the LM should be the minimum requirement prior to attempting a lunar landing; and (5) although a lunar orbit mission should not be a formal step in the program, this should be planned as a contingency in the event of the CSM achieving lunar-mission capability ahead of the LM.

ASPO sent the Block II Redefinition Task Team, led by Frank Borman, to North American Aviation on 27 April. Having the authority to make on-the-spot decisions which previously would have required referral to the Configuration Control Board, it was to oversee the ‘redefinition’ of the Block II spacecraft, responding promptly to questions regarding detail design, quality and reliability, test and checkout, baseline specifications, configuration control, and scheduling. Meanwhile, the company had hired William D. Bergen from the Martin Company to supersede Harrison A. Storms as Apollo Project Manager. Bergen brought with him John P. Healy to manage the production of the first Block II at Downey, and Bastian Hello to run the company’s operations at the Cape.

On 8 May 1967 George Low reaffirmed that AS-205 would launch CSM-101 on an open-ended mission of up to 11 days to evaluate its systems. The next day, James Webb told a Senate committee that this mission would be flown by Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham. When Webb canvassed suggestions for how to impress upon Congress that the Apollo program was recovering from the setback of the fire, George Mueller urged that the Saturn V be flown as soon as possible.

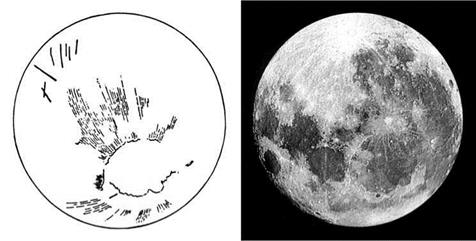

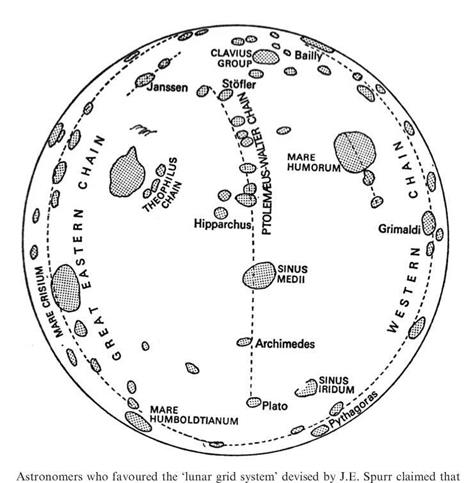

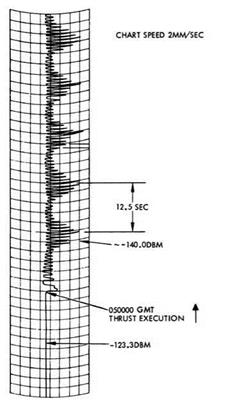

Deep Space Instrumentation Facility automatic gain control variations served to document the initial tumbling of the Surveyor 2 spacecraft.

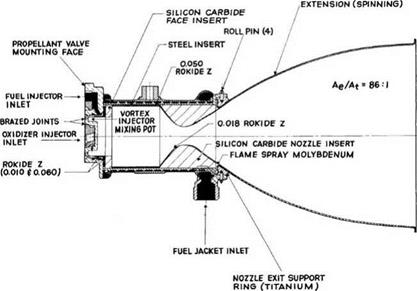

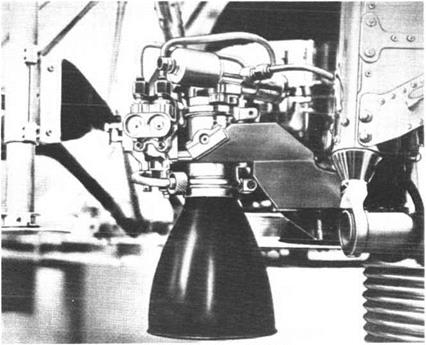

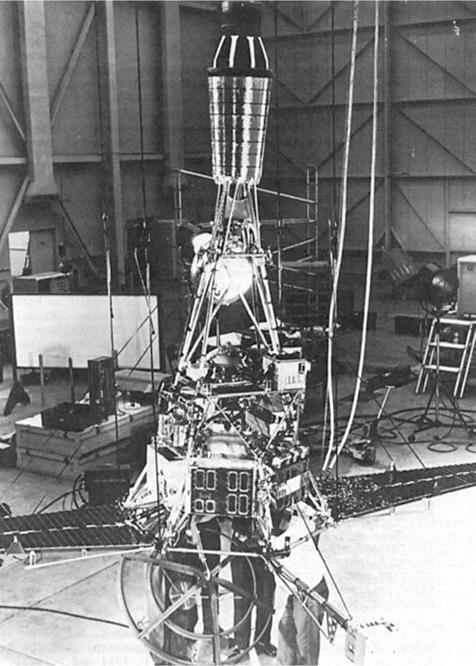

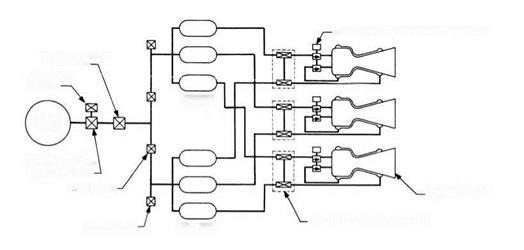

Deep Space Instrumentation Facility automatic gain control variations served to document the initial tumbling of the Surveyor 2 spacecraft. SOLENOID-OPERATED PROPELLANT VALVE

SOLENOID-OPERATED PROPELLANT VALVE