Transitioning from the Supersonic to the Hypersonic: X-7 to X-15

During the 1950s and early 1960s, aviation advanced from flight at high altitude and Mach 1 to flight in orbit at Mach 25. Within the atmosphere, a number of these advances stemmed from the use of the ramjet, at a time when turbojets could barely pass Mach 1 but ramjets could aim at Mach 3 and above. Ramjets needed an auxiliary rocket stage as a booster, which brought their general demise after high-performance afterburning turbojets succeeded in catching up. But in the heady days of the 1950s, the ramjet stood on the threshold of becoming a mainstream engine. Many plans and proposals existed to take advantage of their power for a variety of aircraft and missile applications.

The burgeoning ramjet industry included Marquardt and Wright Aeronautical, though other firms such as Bendix developed them as well. There were also numerous hardware projects. One was the Air Force- Lockheed X-7, an air-launched high-speed propulsion, aerodynamic, and structures testbed. Two were surface-to-air ramjet-powered missiles: the Navy’s ship-based Mach 2.5+ Talos and the Air Force’s Mach 3+ Bomarc. Both went on to years of service, with the Talos flying "in anger” as a MiG-killer and antiradiation SAM-killer in Vietnam. The Air Force also was developing a 6,300-mile-range Mach 3+ cruise missile— the North American SM-64 Navaho—and a Mach 3+ interceptor fighter— the Republic XF-103. Neither entered the operational inventory. The Air Force canceled the troublesome Navaho in July 1957, weeks after the first flight of its rival, Atlas, but some flight hardware remained, and Navaho flew in test for as far as 1,237 miles, though this was a rare success. The XF-103 was to fly at Mach 3.7 using a combined turbojet-ramjet engine. It was to be built largely of titanium, at a time when this metal was little understood; it thus lived for 6 years without approaching flight test. Still, its engine was built and underwent test in December 1956.[564]

The steel-structured X-7 proved surprisingly and consistently productive. The initial concept of the X-7 dated to December 1946 and constituted a three-stage vehicle. A B-29 (later a B-50) served as a "first stage” launch aircraft; a solid rocket booster functioned as a "second stage” accelerating it to Mach 2, at which the ramjet would take over. First flying in April 1951, the X-7 family completed 100 missions between 1955 and program termination in 1960. After achieving its Mach 3 design goal, the program kept going. In August 1957, an X-7 reached Mach 3.95 with a 28-inch diameter Marquardt ramjet. The following April, the X-7 attained Mach 4.31—2,881 mph—with a more-powerful 36-inch Marquardt ramjet. This established an air-breathing propulsion record that remains unsurpassed for a conventional subsonic combustion ramjet.[565]

At the same time that the X-7 was edging toward the hypersonic frontier, the NACA, Air Force, Navy, and North American Aviation had a far more ambitious project underway: the hypersonic X-15. This was Round Two, following the earlier Round One research airplanes that had taken flight faster than sound. The concept of the X-15 was first proposed by Robert Woods, a cofounder and chief engineer of Bell Aircraft (manufacturer of the X-1 and X-2), at three successive meetings of the NACA’s influential Committee on Aerodynamics between October 1951 and June 1952. It was a time when speed was king, when ambitious technologypushing projects were flying off the drawing board. These included the Navaho, X-2, and XF-103, and the first supersonic operational fighters—the Century series of the F-100, F-101, F-102, F-104, and F-105.[566]

Some contemplated even faster speeds. Walter Dornberger, former commander of the Nazi research center at Peenemunde turned senior Bell Aircraft Corporation executive, was advocating BoMi, a proposed skipgliding "Bomber-Missile” intended for Mach 12. Dornberger supported Woods in his recommendations, which were adopted by the NACA’s Executive Committee in July 1952. This gave them the status of policy, while the Air Force added its own support. This was significant because

its budget was 300 times larger than that of the NACA.[567] The NACA alone lacked funds to build the X-15, but the Air Force could do this easily. It also covered the program’s massive cost overruns. These took the airframe from $38.7 million to $74.5 million and the large engine from $10 million to $68.4 million, which was nearly as much as the airframe.[568]

The Air Force had its own test equipment at its Arnold Engineering Development Center (AEDC) at Tullahoma, TN, an outgrowth of the Theodore von Karman technical intelligence mission that Army Air Forces Gen. Henry H. "Hap” Arnold had sent into Germany at the end of the Second World War. The AEDC, with brand-new ground test and research facilities, took care to complement, not duplicate, the NACA’s research facilities. It specialized in air-breathing and rocket-engine testing. Its largest installation accommodated full-size engines and provided continuous flow at Mach 4.75. But the X-15 was to fly well above this, to over Mach 6, highlighting the national facilities shortfall in hypersonic test capabilities existing at the time of its creation.[569]

While the Air Force had the deep pockets, the NACA—specifically Langley—conducted the research that furnished the basis for a design. This took the form of a 1954 feasibility study conducted by John Becker, assisted by structures expert Norris Dow, rocket expert Maxime Faget, configuration and controls specialist Thomas Toll, and test pilot James Whitten. They began by considering that during reentry, the vehicle should point its nose in the direction of flight. This proved impossible, as the heating was too high. He considered that the vehicle might alleviate this problem by using lift, which he was to obtain by raising the nose. He found that the thermal environment became far more manageable. He concluded that the craft should enter with its nose high, presenting its flat undersurface to the atmosphere. The Allen-Eggers paper was in print, and he later wrote that: "it was obvious to us that what we were seeing here was a new manifestation of H. J. Allen’s ‘blunt-body’ principle.”[570]

To address the rigors of the daunting aerothermodynamic environment, Norris Dow selected Inconel X (a nickel alloy from International Nickel) as the temperature-resistant superalloy that was to serve for the aircraft structure. Dow began by ignoring heating and calculated the skin gauges needed only from considerations of strength and stiffness. Then he determined the thicknesses needed to serve as a heat sink. He found that the thicknesses that would suffice for the latter were nearly the same as those that would serve merely for structural strength. This meant that he could design his airplane and include heat sink as a bonus, with little or no additional weight. Inconel X was a wise choice; with a density of 0.30 pounds per cubic inch, a tensile strength of over 200,000 pounds per square inch (psi), and yield strength of 160,000 psi, it was robust, and its melting temperature of over 2,500 °F ensured that the rigors of the anticipated 1,200 °F surface temperatures would not weaken it.[571]

Work at Langley also addressed the important issue of stability. Just then, in 1954, this topic was in the forefront because it had nearly cost the life of the test pilot Chuck Yeager. On the previous December 12, he had flown the X-1A to Mach 2.44 (approximately 1,650 mph). This exceeded the plane’s stability limits; it went out of control and plunged out of the sky. Only Yeager’s skill as a pilot had saved him and his airplane. The problem of stability would be far more severe at higher speeds.[572]

Analysis, confirmed by experiments in the 11-inch wind tunnel, had shown that most of the stability imparted by an aircraft’s tail surfaces was produced by its wedge-shaped forward portion. The aft portion contributed little to the effectiveness because it experienced lower air pressure. Charles McLellan, another Langley aerodynamicist, now proposed to address the problem of hypersonic stability by using tail surfaces that would be wedge-shaped along their entire length. Subsequent tests in the 11-inch tunnel, as mentioned previously, confirmed that this solution worked. As a consequence, the size of the tail surfaces shrank from being almost as large as the wings to a more nearly conventional appearance.[573]

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]() HELIUM

HELIUM

TANKS ‘

EJECTION SEAT-

A schematic drawing of the X-15’s internal layout. NASA.

This study made it possible to proceed toward program approval and the award of contracts both for the X-15 airframe and its power-plant, a 57,000-pound-thrust rocket engine burning a mix of liquid oxygen and anhydrous ammonia. But while the X-15 promised to advance the research airplane concept to over Mach 6, it demanded something more than the conventional aluminum and stainless steel structures of earlier craft such as the X-1 and X-2. Titanium was only beginning to enter use, primarily for reducing heating effects around jet engine exhausts and afterburners. Magnesium, which Douglas favored for its own high-speed designs, was flammable and lost strength at temperatures higher than 600 °F. Inconel X was heat-resistant, reasonably well known, and relatively easily worked. Accordingly, it was swiftly selected as the structural material of choice when Becker’s Langley team assessed the possibility of designing and fabricating a rocket-boosted air-launched hypersonic research airplane. The Becker study, completed in April 1954, chose Mach 6 as the goal and proposed to fly to altitudes as great as 350,000 feet. Both marks proved remarkably prescient: the X-15 eventually flew to 354,200 feet in 1963 and Mach 6.70 in 1967. This was above 100 kilometers and well above the sensible atmosphere. Hence, at that early date, more than 3 years before Sputnik, Becker and his colleagues already were contemplating piloted flight into space.[574]

The X-15: Pioneering Piloted Hypersonics

North American Aviation won the contract to build the X-15. It first flew under power in September 1959, by which time an Atlas had hurled an

|

The North American X-1 5 at NASA’s Flight Research Center (now the Dryden Flight Research Center) in 1961. NASA. |

RVX-2 nose cone to its fullest range. However, as a hypersonic experiment, the X-15 was a complete airplane. It thus was far more complex than a simple reentry body, and it took several years of cautious flight-testing before it reached peak speed of above Mach 6, and peak altitude as well.

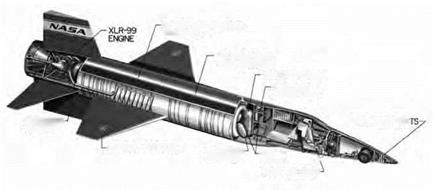

Testing began with two so-called "Little Engines,” a pair of vintage Reaction Motors XLR11s that had earlier served in the X-1 series and the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket. Using these, the X-15 topped the records of the earlier X-2, reaching Mach 3.50 and 136,500 feet. Starting in 1961, using the "Big Engine”—the Thiokol XLR99 with its 57,000 pounds of thrust—the X-15 flew to its Mach 6 design speed and 50+ mile design altitude, with test pilot Maj. Robert White reaching Mach 6.04 and NASA pilot Joseph Walker an altitude of 354,200 feet. After a landing accident, the second X-15 was modified with external tanks and an ablative coating, with Air Force Maj. William "Pete” Knight subsequently flying this variant to Mach 6.70 (4,520 mph) in 1967. However, it sustained severe thermal damage, partly as a result of inadequate understanding of the interactions of impinging hypersonic shock-on-shock flows. It never flew again.[575]

The X-15’s cautious buildup proved a wise approach, for this gave leeway when problems arose. Unexpected thermal expansion leading to localized buckling and deformation showed up during early high-Mach flights. The skin behind the wing leading edge exhibited localized buckling after the first flight to Mach 5.3, but modifications to the wings eliminated hot

spots and prevented subsequent problems, enabling the airplane to reach beyond Mach 6. In addition, a flight to Mach 6.04 caused a windshield to crack because of thermal expansion. This forced redesign of its frame to incorporate titanium, which has a much lower coefficient of expansion. The problem—a rare case in which Inconel caused rather than resolved a heating problem—was fixed by this simple substitution.[576]

Altitude flights brought their own problems, involving potentially dangerous auxiliary power unit (APU) failures. These issues arose in 1962 as flights began to reach well above 100,000 feet; the APUs began to experience gear failure after lubricating oil foamed and lost its lubricating properties. A different oil had much less tendency to foam; it now became standard. Designers also enclosed the APU gearbox within a pressurized enclosure. The gear failures ceased.[577]

The X-15 substantially expanded the use of flight simulators. These had been in use since the famed Link Trainer of Second World War and now included analog computers, but now they also took on a new role as they supported the development of control systems and flight equipment. Analog computers had been used in flight simulation since 1949. Still, in 1955, when the X-15 program began, it was not at all customary to use flight simulators to support aircraft design and development. But program managers turned to such simulators because they offered effective means to study new issues in cockpit displays, control systems, and aircraft handling qualities. A 1956 paper stated that simulation had "heretofore been considered somewhat of a luxury for high-speed aircraft,” but now "has been demonstrated as almost a necessity,” in all three axes, "to insure [sic] consistent and successful entries into the atmosphere.” Indeed, pilots spent much more time practicing in simulators than they did in actual flight, as much as an hour per minute of actual flying time.[578]

The most important flight simulator was built by North American. Located originally in Los Angeles, Paul Bikle, the Director of NASA’s Flight Research Center, moved it to that Center in 1961. It replicated the X-15 cockpit and included actual hydraulic and control-system hardware. Three analog computers implemented equations of motion that governed translation and rotation of the X-15 about all three axes, transforming pilot inputs into instrument displays.[579]

The North American simulator became critical in training X-15 pilots as they prepared to execute specific planned flights. A particular mission might take little more than 10 minutes, from ignition of the main engine to touchdown on the lakebed, but a test pilot could easily spend 10 hours making practice runs in this facility. Training began with repeated trials of the normal flight profile with the pilot in the simulator cockpit and a ground controller close at hand. The pilot was welcome to recommend changes, which often went into the flight plan. Next came rehearsals of off-design missions: too much thrust from the main engine, too high a pitch angle when leaving the stratosphere.

Much time was spent practicing for emergencies. The X-15 had an inertial reference unit that used analog circuitry to display attitude, altitude, velocity, and rate of climb. Pilots dealt with simulated failures in this unit as they worked to complete the normal mission or, at least, to execute a safe return. Similar exercises addressed failures in the stability augmentation system. When the flight plan raised issues of possible flight instability, tests in the simulator used highly pessimistic assumptions concerning stability of the vehicle. Other simulations introduced in-flight failures of the radio or Q-ball multifunction sensor. Premature engine shutdown imposed a requirement for safe landing on an alternate lakebed that was available for emergency use.[580]

The simulations indeed had realistic cockpit displays, but they left out an essential feature: the g-loads, produced both by rocket thrust and by deceleration during reentry. In addition, a failure of the stability augmentation system, during reentry, could allow the airplane to oscillate

in pitch and yaw. This changed the drag characteristics and imposed a substantial cyclical force.

To address such issues, investigators installed a flight simulator within the gondola of an existing centrifuge at the Naval Air Development Center in Johnsville, PA. The gondola could rotate on two axes while the centrifuge as a whole was turning. It not only produced g-forces; its g-forces increased during the simulated rocket burn. The centrifuge imposed such forces anew during reentry while adding a cyclical component to give the effect of an oscillation in yaw or pitch.[581]

There also were advances in pressure suits, under development since the 1930s. Already an early pressure suit had saved the life of Maj. Frank K. Everest during a high-altitude flight in the X-1, when it had suffered cabin decompression from a cracked canopy. Marine test pilot Lt. Col. Marion Carl had worn another during a flight to 83,235 feet in the D-558-2 Skyrocket in 1953, as had Capt. Iven Kincheloe during his record flight to 126,200 feet in the Bell X-2 in 1956. But these early suits, while effective in protecting pilots, were almost rigid when inflated, nearly immobilizing them. In contrast, the David G. Clark Company, a girdle manufacturer, introduced a fabric that contracted in circumference while it stretched in length. An exchange between these effects created a balance that maintained a constant volume, preserving a pilot’s freedom of movement. The result was the Clark MC-2 suit, which, in addition to the X-15, formed the basis for American spacesuit development from Project Mercury forward. Refined as the A/P22S-2, the X-15’s suit became the standard high-altitude pressure suit for NASA and the Air Force. It formed the basis for the Gemini suit and, after 1972, was adopted by the U. S. Navy as well, subsequently being employed by pilots and aircrew in the SR-71, U-2, and Space Shuttle.[582]

The X-15 also accelerated development of specialized instrumentation, including a unique gimbaled nose sensor developed by Northrop. It furnished precise speed and positioning data by evaluation of dynamic pressure ("q” in aero engineering shorthand), and thus was known as the Q-ball. The Q-ball took the form of a movable sphere set in the nose of the craft, giving it the appearance of the enlarged tip of a ballpoint pen. "The Q-ball is a go-no go item,” NASA test pilot Joseph Walker told Time magazine reporters in 1961, adding: "Only if she checks okay do we go.”[583] The X-15 also incorporated "cold jet” hydrogen peroxide reaction controls for maintaining vehicle attitude in the tenuous upper atmosphere, when dynamic air pressure alone would be insufficient to permit adequate flight control functionality. When Iven Kincheloe reached 126,200 feet, his X-2 was essentially a free ballistic object, uncontrollable in pitch, roll, and yaw as it reached peak altitude and then began its descent. This situation made reaction controls imperative for the new research airplane, and the NACA (later NASA) had evaluated them on a so-called "Iron Cross” simulator on the ground and then in flight on the Bell X-1B and on a modified Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. They then proved their worth on the X-15 and, as with the Clark pressure suit, were incorporated on Mercury and subsequent American spacecraft.

The X-15 introduced a side stick flight controller that the pilot would utilize during acceleration (when under loads of approximately 3 g’s), relying on a fighter-type conventional control column for approach and landing. The third X-15 had a very different flight control system than the other two, differing greatly from the now-standard stability-augmented hydromechanical system carried by operational military and civilian aircraft. The third aircraft introduced a so-called "adaptive” flight control system, the MH-96. Built by Minneapolis Honeywell, the MH-96 relied on rate gyros, which sensed rates of motion in pitch, roll, and yaw. It also incorporated "gain,” defined as the proportion between sensed rates of angular motion and a deflection of the ailerons or other controls. This variable gain, which changed automatically in response to flight conditions, functioned to maintain desired handling qualities across the spectrum of X-15 performance. This arrangement made it possible to introduce blended reaction and aerodynamic controls on the same stick, with this blending occurring automatically in response to

the values determined for gain as the X-15 flew out of the atmosphere and back again. Experience, alas, would reveal the MH-96 as an immature, troublesome system, one that, for all its ambition, posed significant headaches. It played an ultimately fatal role in the loss of X-15 pilot Maj. Michael Adams in 1967.[584]

The three X-15s accumulated a total of 199 flights from 1959 through

1968. As airborne instruments of hypersonic research, they accumulated nearly 9 hours above Mach 3, close to 6 hours above Mach 4, and 87 minutes above Mach 5. Many concepts existed for X-15 derivatives and spinoffs, including using it as a second stage to launch small satellite-lofting boosters, to be modified with a delta wing and scram – jet, and even to form the basis itself for some sort of orbital spacecraft; for a variety of reasons, NASA did not proceed with any of these. More significantly, however, was the strong influence the X-15 exerted upon subsequent hypersonic projects, particularly the National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility (NHFRF, pronounced "nerf”), intended to reach Mach 8.

A derivative of the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory’s X-24C study effort, NHFRF was also to cruise at Mach 6 for 40 seconds. A joint Air Force-NASA committee approved a proposal in July 1976 with an estimated program cost of $200 million, and NHFRF had strong support from NASA’s hypersonic partisans in the Langley and Dryden Centers. Unfortunately, its rising costs, at a time when the Shuttle demanded an ever-increasing proportion of the Agency’s budget and effort, doomed it, and it was canceled in September 1977. Overall, the X-15 set speed and altitude records that were not surpassed until the advent of the Space Shuttle.[585]

The X-20 Dyna-Soar

During the 1950s, as the X-15 was taking shape, a parallel set of initiatives sought to define a follow-on hypersonic program that could actually achieve orbit. They were inspired in large measure by the 1938-1944 Silbervogel ("Silver Bird”) proposal of Austrian space flight advocate Eugen Sanger and his wife, mathematician Irene Sanger-Bredt, which greatly influenced postwar Soviet, American, and European thinking about hypersonics and long-range "antipodal” flight. Influenced by Sanger’s work and urged onward by the advocacy of Walter Dornberger, Bell Aircraft Corporation in 1952 proposed the BoMi, intended to fly 3,500 miles. Bell officials gained funding from the Air Force’s Wright Air Development Center (WADC) to study longer-range 4,000-mile and 6,000-mile systems under the aegis of Air Force project MX-2276.

Support took a giant step forward in February 1956, when Gen. Thomas Power, Chief of the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC, predecessor of Air Force Systems Command) and a future Air Force Chief of Staff, stated that the service should stop merely considering such radical craft and instead start building them. With this level of interest, events naturally moved rapidly. A month later, Bell received a study contract for Brass Bell, a follow-on Mach 15 rocket-lofted boost – glider for strategic reconnaissance. Power preferred another orbital glider concept, RoBo (for Rocket Bomber), which was to serve as a global strike system. To accelerate transition of hypersonics from the research to the operational community, the ARDC proposed its own concept, Hypersonic Weapons Research and Development Supporting System (HYWARDS). With so many cooks in the kitchen, the Air Force needed a coordinated plan. An initial step came in December 1956, as Bell raised the velocity of Brass Bell to Mach 18. A month later, a group headed by John Becker, at Langley, recommended the same design goal for HYWARDS. RoBo still remained separate, but it emerged as a longterm project that could be operational by the mid-1970s.[586]

NACA researchers split along centerlines over the issue of what kind of wing design to employ for HYWARDS. At NACA Ames, Alfred Eggers and Clarence Syvertson emphasized achieving maximum lift. They proposed a high-wing configuration with a flat top, calculating its hypersonic

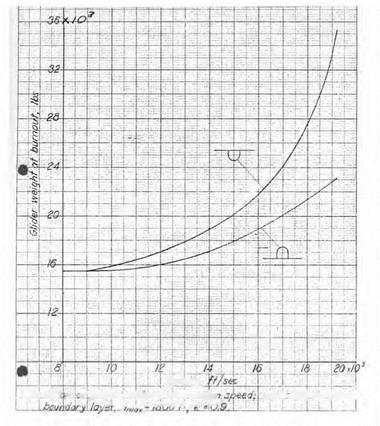

life-to-drag (L/D) as 6.85 and measuring a value of 6.65 during hypersonic tunnel tests. Langley researchers John Becker and Peter Korycinski argued that Ames had the configuration "upside down.” Emphasizing lighter weight, they showed that a flat-bottom Mach 18 shape gave a weight of 21,400 pounds, which rose only modestly at higher speeds. By contrast, the Ames "flat-top” weight was 27,600 pounds and rising steeply. NASA officials diplomatically described the Ames and Langley HYWARDS concepts respectively as "high L/D” and "low heating,” but while the imbroglio persisted, there still was no acceptable design. It fell to Becker and Korycinski to break the impasse in August 1957, and they did so by considering heating. It was generally expected that such craft required active cooling. But Becker and his Langley colleagues found that a glider of global range achieved peak uncooled skin temperatures of 2,000 °F, which was survivable by using improved materials. Accordingly, the flat-bottom design needed no coolant, dramatically reducing both its weight and complexity.[587]

This was a seminal conclusion that reshaped hypersonic thinking and influenced all future development down to the Space Shuttle. In October 1957, coincident with the Soviet success with Sputnik, the ARDC issued a coordinated plan that anticipated building HYWARDS for research at 18,000 feet per second, following it with Brass Bell for reconnaissance at the same speed and then RoBo, which was to carry nuclear bombs into orbit. HYWARDS now took on the new name of Dyna-Soar, for "Dynamic Soaring,” an allusion to the Sanger-legacy skip-gliding hypersonic reentry. (It was later designated X-20.) To the NACA, it constituted a Round Three following the Round One X-1, X-2, and Skyrocket, and the Round Two X-15.

The flat-bottom configuration quickly showed that it was robust enough to accommodate flight at much higher speeds. In 1959, Herbert York, the Defense Director of Research and Engineering, stated that Dyna-Soar was to fly at 15,000 mph, lofted by the Martin Company’s Titan I missile, though this was significantly below orbital speed. But

|

|

|

|

This 1957 Langley trade-study shows weight advantage of flat-bottom reentry vehicles at higher Mach numbers. This led to abandonment of high-wing designs in favor of flat-bottom ones such as the X-20 Dyna-Soar and the Space Shuttle. NASA.

during subsequent years it changed to the more-capable Titan II and then to the powerful Titan III-C. With two solid-fuel boosters augmenting its liquid hypergolic main stage, it could easily boost Dyna-Soar to the 18,000 mph necessary for it to achieve orbit. A new plan of December 1961 dropped suborbital missions and called for "the early attainment of orbital flight.”[588]

By then, though, Dyna-Soar was in deep political trouble. It had been conceived initially as a prelude to the boost-glider Brass Bell for

|

This full-size mockup of the X-20 gives an indication of its small, compact design. USAF. |

reconnaissance and to the orbital RoBo for bombardment. But Brass Bell gave way to a purpose-built concept for a small-piloted station, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), which could carry more sophisticated reconnaissance equipment. (Ironically, though a team of MOL astronauts was selected, MOL itself likewise was eventually canceled.) RoBo, a strategic weapon, fell out of the picture completely, for the success of the solid-propellant Minuteman ICBM established the silo – launched ICBM as the Nation’s prime strategic force, augmented by the Navy’s fleet of Polaris-launching ballistic missile submarines.[589]

In mid-196l, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara directed the Air Force to justify Dyna-Soar on military grounds. Service advocates responded by proposing a host of applications, including orbital reconnaissance, rescue, inspection of Soviet spacecraft, orbital bombardment,

and use of the craft as a ferry vehicle. McNamara found these rationalizations unconvincing but was willing to allow the program to proceed as a research effort, at least for the time being. In an October 1961 memo to President John F. Kennedy, he proposed to "re-orient the program to solve the difficult technical problems involved in boosting a body of high lift into orbit, sustaining man in it and recovering the vehicle at a designated place.”[590] This reorientation gave the project 2 more years of life.

Then in 1963, he asked what the Air Force intended to do with it after using it to demonstrate maneuvering entry. He insisted he could not justify continuing the program if it was a dead-end effort with no ultimate purpose. But it had little potential utility, for it was not a cargo rocket, nor could it carry substantial payloads, nor could it conduct long – duration missions. And so, in December McNamara canceled it, after 6 years of development time, a Government contract investment of $410 million, the expenditure of 16 million man-hours by nearly 8,000 contractor personnel, 14,000 hours of wind tunnel testing, 9,000 hours of simulator runs, and the preparation of 3,035 detailed technical reports.[591]

Ironically, by time of its cancellation, the X-20 was so far advanced that the Air Force had already set aside a block of serial numbers for the 10 production aircraft. Its construction was well underway, Boeing having completed an estimated 42 percent of design and fabrication tasks.[592] Though the X-20 never flew, portions of its principal purposes were fulfilled by other programs. Even before cancellation, the Air Force launched the first of several McDonnell Aerothermodynamic/ elastic Structural Systems Environmental Test (ASSET) hot-structure radiative-cooled flat-bottom cone-cylinder shapes sharing important configuration similarities to the Dyna-Soar vehicle. Slightly later, its Project PRIME demonstrated cross-range maneuver after atmospheric entry. This used the Martin SV-5D lifting body, a vehicle differing significantly from the X-20 but which complemented it nonetheless. In this fashion, the Air Force succeeded at least partially in obtaining lifting reentry data from winged vehicles and lifting bodies that widened the future prospects for reentry.

Hot Structures and Return from Space: X-20’s Legacy and ASSET

Dyna-Soar never flew, but it sharply extended both the technology and the temperature limits of hot structures and associated aircraft elements, at a time when the American space program was in its infancy.[593] The United States successfully returned a satellite from orbit in April 1959, while ICBM nose cones were still under test, when the Discoverer II test vehicle supporting development of the National Reconnaissance Office’s secret Corona spy satellite returned from orbit. Unfortunately, it came down in Russian-occupied territory far removed from its intended recovery area near Hawaii. Still, it offered proof that practical hypersonic reentry and recovery were at hand.

An ICBM nose cone quickly transited the atmosphere, whereas recoverable satellite reentry took place over a number of minutes. Hence a satellite encountered milder aerothermodynamic conditions that imposed strong heat but brought little or no ablation. For a satellite, the heat of ablation, measured in British thermal units (BTU) per pound of protective material, was usually irrelevant. Instead, insulative properties were more significant: Teflon, for example, had poor ablative properties but was an excellent insulator.[594]

Production Dyna-Soar vehicles would have had a four-flight service life before retirement or scrapping, depending upon a hot structure comprised of various materials, each with different but complementary properties. A hot structure typically used a strong material capable of withstanding intermediate temperatures to bear flights loads. Set off from it were outer panels of a temperature-resistant material that did not have to support loads but that could withstand greatly elevated temperatures as high as 3,000 °F. In between was a lightweight insulator (in Dyna-Soar’s case, Q-felt, a silica fiber from the firm of Johns Manville). It had a tendency to shrink, thus risking dangerous gaps where high heat could bypass it. But it exhibited little shrinkage above 2,000 °F

and could withstand 3,000 °F. By "preshrinking” this material, it qualified for operational use.[595]

For its primary structure, Dyna-Soar used Rene 41, a nickel alloy that included chromium, cobalt, and molybdenum. Its use was pioneered by General Electric for hot-section applications in its jet engines. The alloy had room temperature yield strength of 130,000 psi, declining slightly at 1,200 °F, and was still strong at 1,800 °F. Some of the X-20’s panels were molybdenum alloy, which offered clear advantages for such hot areas as the wing leading edges. D-36 columbium alloy covered most other areas of the vehicle, including the flat underside of the wings.

These panels had to resist flutter, which brought a risk of cracking because of fatigue, as well as permitting the entry of superheated hypersonic flows that could destroy the internal structure within seconds. Because of the risks to wind tunnels from hasty and ill-considered flutter testing (where a test model for example can disintegrate, damaging the interior of the tunnel), X-20 flutter testing consumed 18 months of Boeing’s time. Its people started testing at modest stress levels and reached levels that exceeded the vehicle’s anticipated design requirements.[596]

The X-20’s nose cap had to function in a thermal and dynamic pressure environment more extreme even than that experienced by the X-15’s Q-ball. It was a critical item that faced temperatures of 3,680 °F, accompanied by a daunting peak heat flux of 143 BTU per square foot per second. Both Boeing and its subcontractor Chance Vought pursued independent approaches to development, resulting in two different designs. Vought built its cap of siliconized graphite with an insulating layer of a temperature-resistant zirconium oxide ceramic tiles. Their melting point was above 4,500 °F, and they covered its forward area, being held in place by thick zirconium oxide pins. The Boeing design was simpler, using a solid zirconium oxide nose cap reinforced against cracking with two screens of platinum-rhodium wire. Like the airframe, the nose caps were rated through four orbital flights and reentries.[597]

Generally, the design of the X-20 reflected the thinking of Langley’s John Becker and Peter Korycinski. It relied on insulation and radiation of the accumulated thermal load for primary thermal protection. But portions of the vehicle demanded other approaches, with specialized areas and equipment demanding specialized solutions. Ball bearings, facing a 1,600 °F thermal environment, were fabricated as small spheres of Rene 41 nickel alloy covered with gold. Antifriction bearings used titanium carbide with nickel as a binder. Antenna windows had to survive hot hypersonic flows yet be transparent to radio waves. A mix of oxides of cobalt, aluminum, and nickel gave a coating that showed a suitable emittance while furnishing requisite temperature protection.

The pilot looked through five clear panes: three that faced forward and two on the sides. The three forward panes were protected by a jetti – sonable protective shield and could only be used below Mach 5 after reentry, but the side ones faced a less severe aerothermodynamic environment and were left unshielded. But could the X-20 be landed if the protective shield failed to jettison after reentry? NASA test pilot Neil Armstrong, later the first human to set foot upon the Moon, flew approaches using a modified Douglas F5D Skylancer. He showed it was possible to land the Dyna-Soar using only visual cues obtained through the side windows.

The cockpit, equipment bay, and a power bay were thermally isolated and cooled via a "water wall” using lightweight panels filled with a jelled water mix. The hydraulic system was cooled as well. To avoid overheating and bursting problems with conventional inflated rubber tires, Boeing designed the X-20 to incorporate tricycle-landing skids with wire brush landing pads.[598] Dyna-Soar, then, despite never having flown, significantly advanced the technology of hypersonic aerospace vehicle design. Its contributions were many and can be illustrated by examining the confidence with which engineers could approach the design of critical technical elements of a hypersonic craft, in 1958 (the year North American began fabricating the X-15) and 1963 (the year Boeing began fabricating the X-20):[599] In short, within the 5 years that took the X-20 from a paper study to a project well underway, the "art of the possible”

|

TABLE 1 INDUSTRY HYPERSONIC "DESIGN CONFIDENCE" AS MEASURED BY ACHIEVABLE DESIGN TEMPERATURE CRITERIA, °F |

||

|

ELEMENT |

X-15 |

X-20 |

|

Nose cap |

3,200 |

4,300 |

|

Surface panels |

1,200 |

2,750 |

|

Primary structure |

1,200 |

1,800 |

|

Leading edges |

1,200 |

3,000 |

|

Control surfaces |

1,200 |

1,800 |

|

Bearings |

1,200 |

1,800 |

in hypersonics witnessed a one-third increase in possible nose cap temperatures, a more than double increase in the acceptable temperatures of surface panels and leading edges, and a one-third increase in the acceptable temperatures of primary structures, control surfaces, and bearings.

The winddown and cancellation of Dyna-Soar coincided with the first flight tests of the much smaller but nevertheless still very technically ambitious McDonnell ASSET hypersonic lifting reentry test vehicle. Lofted down the Atlantic Test Range on modified Thor and Thor-Delta boosters, they demonstrated reentry at over Mach 18. ASSET dated to 1959, when Air Force hypersonic advocates advanced it as a means of assessing the accuracy of existing hypersonic theory and predictive techniques. In 1961, McDonnell Aircraft, a manufacturer of fighter aircraft and also the Project Mercury spacecraft, began design and fabrication of ASSET’s small sharply swept delta wing flat-bottom boost-gliders. They had a length of 69 inches and a span of 55 inches.

Though in many respects they resembled the soon-to-be-canceled X-20, unlike that larger, crewed transatmospheric vehicle, the ASSET gliders were more akin to lifting nose cone shapes. Instead of the X-20’s primary reliance upon Rene 41, the ASSET gliders largely used colum- bium alloys, with molybdenum alloy on their forward lower heat shield, graphite wing leading edges, various insulative materials, and colum – bium, molybdenum, and graphite coatings as needed. There were also three nose caps: one fabricated from zirconium oxide rods, another from tungsten coated with thorium, and a third of siliconized graphite coated with zirconium oxide. Though all six ASSETs looked alike, they were built in two differing variants: four Aerothermodynamic Structural Vehicles (ASV) and two Aerothermodynamic Elastic Vehicles (AEV). The former reentered from higher velocities (between 16,000 and 19,500 feet

per second) and altitudes (from 202,000 to 212,000 feet), necessitating use of two-stage Thor-Delta boosters. The latter (only one of which flew successfully) used a single-stage Thor booster and reentered at 13,000 feet per second from an altitude of 173,000 feet. It was a hypersonic flutter research vehicle, analyzing as well the behavior of a trailing-edge flap representing a hypersonic control surface. Both the ASV and AEV flew with a variety of experimental panels installed at various locations and fabricated by Boeing, Bell, and Martin.[600] The ASSET program conducted six flights between September 1963 and February 1965, all successful save for one AEV launch in March 1964. Though intended for recovery from the Atlantic, only one survived the rigors of parachute deployment, descent, and being plunged into the ocean. But that survivor, the ASV – 3, proved to be in excellent condition, with the builder, International Harvester, rightly concluding it "could have been used again.”[601] ASV-4, the best flight flown, was also the last one, with the final flight-test report declaring that it returned "the highest quality data of the ASSET program.” It flew at a peak speed of Mach 18.4, including a hypersonic glide that covered 2,300 nautical miles.[602]

Overall, the ASSET program scored a host of successes. It was all the more impressive for the modest investment made in its development: just $21.2 million. It furnished the first proof of the magnitude and seriousness of upper-surface leeside heating and the dangers of hypersonic flow impingement into interior structures. It dealt with practical issues of fabrication, including fasteners and coatings. It contributed to understanding of hypersonic flutter and of the use of movable control surfaces. It also demonstrated successful use of an attitude-adjusting reaction control system, in near vacuum and at speeds much higher than those of the X-15. It complemented Dyna-Soar and left the aerospace industry believing that hot structure design technology would be the normative technical approach taken on future launch vehicles and orbital spacecraft.[603]

|

TABLE 2 MCDONNELL ASSET FLIGHT TEST PROGRAM |

|||||

|

DATE |

VEHICLE |

BOOSTER |

VELOCITY (FEET/ SECOND) |

ALTITUDE (FEET) |

RANGE (NAUTICAL MILES) |

|

Sept. 1 8, 1963 |

ASV-1 |

Thor |

16,000 |

205,000 |

987 |

|

Mar. 24, 1964 |

ASV-2 |

Thor-Delta |

18,000 |

195,000 |

1,800 |

|

July 22, 1964 |

ASV-3 |

Thor-Delta |

19,500 |

225,000 |

1,830 |

|

Oct. 27, 1964 |

AEV-1 |

Thor |

13,000 |

168,000 |

830 |

|

Dec. 8, 1964 |

AEV-2 |

Thor |

13,000 |

1 87,000 |

620 |

|

Feb. 23, 1965 |

ASV-4 |

Thor-Delta |

19,500 |

206,000 |

2,300 |

Hypersonic Aerothermodynamic Protection and the Space Shuttle

Certainly over much of the Shuttle’s early conceptual period, advocates thought such logistical transatmospheric aerospace craft would employ hot structure thermal protection. But undertaking such structures on large airliner-size vehicles proved troublesome and thus premature. Then, as though given a gift, NASA learned that Lockheed had built a pilot plant and could mass-produce silica "tiles” that could be attached to a conventional aluminum structure, an approach far more appealing than designing a hot structure. Accordingly, when the Agency undertook development of the Space Shuttle in the 1970s, it selected this approach, meaning that the new Shuttle was, in effect, a simple aluminum airplane. Not surprisingly, Lockheed received a NASA subcontract in 1973 for the Shuttle’s thermal-protection system.

Lockheed had begun its work more than a decade earlier, when investigators at Lockheed Missiles and Space began studying ceramic fiber mats, filing a patent on the technology in December 1960. Key people included R. M. Beasley, Ronald Banas, Douglas Izu, and Wilson Schramm. By 1965, subsequent Lockheed work had led to LI-1500, a material that was 89 percent porous and weighed 15 pounds per cubic foot (lb/ft3). Thicknesses of no more than an inch protected test surfaces during simulations of reentry heating. LI-1500 used methyl methacrylate (Plexiglas), which volatilized when hot, producing an outward

flow of cool gas that protected the heat shield, though also compromising its reusability.[604]

Lockheed’s work coincided with NASA plans in 1965 to build a space station as is main post-Apollo venture and, consequently, the first great wave of interest in designing practical logistical Shuttle-like spacecraft to fly between Earth and the orbital stations. These typically were conceived as large winged two-stage-to-orbit systems with fly-back boosters and orbital spaceplanes. Lockheed’s Maxwell Hunter devised an influential design, the Star Clipper, with two expendable propellant tanks and LI-1500 thermal protection.[605] The Star Clipper also was large enough to benefit from the Allen-Eggers blunt-body principle, which lowered its temperatures and heating rates during reentry. This made it possible to dispense with the outgassing impregnant, permitting use—and, more importantly, reuse—of unfilled LI-1500. Lockheed also introduced LI-900, a variant of LI-1500 with a porosity of 93 percent and a weight of only 9 pounds per cubic foot. As insulation, both LI-900 and LI-1500 were astonishing. Laboratory personnel found that they could heat a tile in a furnace until it was white hot, remove it, allow its surface to cool for a couple of minutes, and pick it up at its edges with their fingers, with its interior still glowing at white heat.[606]

Previous company work had amounted to general materials research. But Lockheed now understood in 1971 that NASA wished to build the Shuttle without simultaneously proceeding with the station, opening a strong possibility that the company could participate. The program had started with a Phase A preliminary study effort, advancing then to Phase B, which was much more detailed. Hot structures were initially ascendant but posed serious challenges, as NASA Langley researchers found when they tried to build a columbium heat shield suitable for the Shuttle. The exercise showed that despite the promise of reusability and long life, coatings were fragile and damaged easily, leading to rapid oxygen-induced embrittlement at high temperatures. Unprotected columbium oxidized particularly readily and, when hot, could burst into flame. Other refractory metals were available, but they were little understood because they had been used mostly in turbine blades.

Even titanium amounted literally to a black art. Only one firm, Lockheed, had significant experience with a titanium hot structure. That experience came from the Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored Blackbird strategic reconnaissance program, so most of the pertinent shop-floor experience was classified. The aerospace community knew that Lockheed had experienced serious difficulties in learning how to work with titanium, which for the Shuttle amounted to an open invitation to difficulties, delays, and cost overruns.

The complexity of a hot structure—with large numbers of clips, brackets, standoffs, frames, beams, and fasteners—also militated against its use. Each of the many panel geometries needed their own structural analysis that was to show with confidence that the panel could withstand creep, buckling, flutter, or stress under load, and in the early computer era, this posed daunting analytical challenges. Hot structures were also known generally to have little tolerance for "overtemps,” in which temperatures exceeded the structure’s design point.[607]

Thus, having taken a long look at hot structures, NASA embraced the new Lockheed pilot plant and gave close examination to Shuttle designs that used tiles, which were formally called Reusable Surface Installation (RSI). Again, the choice of hot structures versus RSI reflected the deep pockets of the Air Force, for hot structures were

costly and complex. But RSI was inexpensive, flexible, and simple. It suited NASA’s budget while hot structures did not, so the Agency chose it.

In January 1972, President Richard M. Nixon approved the Shuttle as a program, thereby raising it to the level of a Presidential initiative. Within days, Dale Myers, a senior official, announced that NASA had made the basic decision to use RSI. The North American Rockwell concept that won the $2.6 billion prime contract in July therefore specified RSI as well—but not Lockheed’s. North American Rockwell’s version came from General Electric and was made from mullite.[608]

Which was better, the version from GE or the one from Lockheed? Only tests would tell—and exposure to temperature cycles of 2,300 °F gave Lockheed a clear advantage. NASA then added acoustic tests that simulated the loud roars of rocket flight. This led to a "sudden-death shootout,” in which competing tiles went into single arrays at NASA Johnson. After 20 cycles, only Lockheed’s entrants remained intact. In separate tests, Lockheed’s LI-1500 withstood 100 cycles to 2,500 °F and survived a thermal overshoot to 3,000 °F as well as an acoustic overshoot to 174 decibels (dB).

Lockheed won the thermal-protection subcontract in 1973, with NASA specifying LI-900 as the baseline RSI. The firm responded by preparing to move beyond the pilot-plant level and to construct a full-scale production facility in Sunnyvale, CA. With this, tiles entered the mainstream of thermal protection systems available for spacecraft design, in much the same way that blunt bodies and ablative approaches had before them, first flying into space aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia in April 1981. But getting them operational and into space was far from easy.[609]