Inertial Coupling: Dangerous Byproduct of High-Speed Design

The progression of aircraft flight speeds from subsonic to transonic and on into the supersonic changed the proportional relationship of wing to fuselage. As speed rose, the ratio of span to fuselage length decreased. At the onset of the subsonic era, the Wright Flyer had a wingspan-to – fuselage length ratio of 1.91. The SPAD XIII fighter of World War I was 1.30. The Second World War’s P-51D decreased to 1.14. Then came the supersonic era: the XS-1 was 0.90. In 1953, the F-100A, lowered the ratio to 0.80, and the F-104A of 1954 cut this in half, to 0.40. The radical X-3 had a remarkably slender wingspan-to-fuselage length ratio of just 0.34: not without reason was it nicknamed the "Stiletto.” But while the dramatic increase in fuselage length at the expense of span spoke to the need to reduce wing-aspect ratio and increase fuselage fineness ratio to achieve idealized supersonic shaping, any resulting aerodynamic benefit came only at the price of significant performance limitations and risk.

Increasing fuselage length while reducing span dramatically changed the mass distribution of these new designs: whereas earlier airplanes had most of their mass concentrated along the span of their wings, as the wing-fuselage ratio changed from well above 1.0 to well below this figure, the distribution of mass shifted to along the fuselage. Since a long forward fuselage inherently reduces directional stability, and since the small low aspect ratio wings of these airplanes reduced their roll stability, a potentially deadly mix of technical circumstances existed to

produce a major crisis: the onset of transonic and supersonic inertial coupling, also termed roll-coupling.

![]() William Hewitt Phillips of the NACA’s Langley laboratory had first forecast inertial coupling. His pronouncement sprang from a fortuitous experience while supervising tests of a large XS-1 "falling body” model in the summer of 1947. The model (dropped from a high-flying B-29 over a test range near Langley to assess XS-1 elevator control effectiveness as it approached Mach 1) incorporated a simple autopilot and was intended to rotate slowly as it fell, so as to maintain a "predictable trajectory.”[69] But after the drop, things went rapidly awry. The model experienced violent pitching and rapid rolling "well below” the speed of sound and fell so far from its planned impact point that it literally disappeared from history. But optical observations, coupled with telemetric data, led Phillips to conclude that "some kind of gyroscopic effect” had taken place. Intrigued, he drew upon coursework from Professors Manfred Rauscher and Charles Stark Draper of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using the analogy of the coupling dynamics of a rotating rod. He substituted the values obtained from the falling XS-1 model, discovering that "the results clearly showed the possibility of a divergent motion. . . . The instability was likely to occur when the values of longitudinal stability and directional stability were markedly different and when a large amount of the weight was distributed along the fuselage.”[70] Hewitt subsequently published a seminal NACA Technical Note in 1948, which presciently concluded: "Design trends of very highspeed aircraft, which include short wing spans, fuselages of high density, and flight at high altitude, all tend to increase the inertia forces due to rolling in comparison with the aerodynamic restoring forces provided by the longitudinal and directional stabilities. It is therefore desirable to investigate the effects of rolling on the longitudinal and directional stabilities of these aircraft. . . . The rolling motion introduces coupling between the longitudinal and lateral motion of the aircraft.”[71] Out of

William Hewitt Phillips of the NACA’s Langley laboratory had first forecast inertial coupling. His pronouncement sprang from a fortuitous experience while supervising tests of a large XS-1 "falling body” model in the summer of 1947. The model (dropped from a high-flying B-29 over a test range near Langley to assess XS-1 elevator control effectiveness as it approached Mach 1) incorporated a simple autopilot and was intended to rotate slowly as it fell, so as to maintain a "predictable trajectory.”[69] But after the drop, things went rapidly awry. The model experienced violent pitching and rapid rolling "well below” the speed of sound and fell so far from its planned impact point that it literally disappeared from history. But optical observations, coupled with telemetric data, led Phillips to conclude that "some kind of gyroscopic effect” had taken place. Intrigued, he drew upon coursework from Professors Manfred Rauscher and Charles Stark Draper of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using the analogy of the coupling dynamics of a rotating rod. He substituted the values obtained from the falling XS-1 model, discovering that "the results clearly showed the possibility of a divergent motion. . . . The instability was likely to occur when the values of longitudinal stability and directional stability were markedly different and when a large amount of the weight was distributed along the fuselage.”[70] Hewitt subsequently published a seminal NACA Technical Note in 1948, which presciently concluded: "Design trends of very highspeed aircraft, which include short wing spans, fuselages of high density, and flight at high altitude, all tend to increase the inertia forces due to rolling in comparison with the aerodynamic restoring forces provided by the longitudinal and directional stabilities. It is therefore desirable to investigate the effects of rolling on the longitudinal and directional stabilities of these aircraft. . . . The rolling motion introduces coupling between the longitudinal and lateral motion of the aircraft.”[71] Out of

this came the expression "inertial coupling” and its more descriptive equivalent, "roll-coupling.” Phillips continued his research on roll-coupling and rolling maneuvers in accelerated flight, noting in 1949 that high-speed rolls could generate "exceptionally large” sideslip loads on a vertical fin that might risk structural failure. He concluded: "The provision of adequate directional stability, especially at small angles of sideslip, in order to prevent excessive sideslipping in rolls at high speed is therefore important from structural considerations as well as from the standpoint of providing desirable flying qualities.”[72]

![]() In the summer of 1952, as part of an investigation effort studying coupled lateral and longitudinal oscillations, researchers at the NACA’s Pilotless Aircraft Research Division at Wallops Island, VA, fired a series of large rocket-boosted swept wing model airplanes. Spanning over 3 feet, but with a length of nearly 6 feet, they had the general aerodynamic shape of the D-558-2 as originally conceived: with a slightly shorter vertical fin. These models accelerated to supersonic speed and then, after rocket burnout and separation, glided onward while onboard telemetry instrumentation relayed a continuous stream of key performance and behavior parameters as they decelerated through the speed of sound before diving into the sea. On August 6, 1952, technicians launched one equipped with a small pulse rocket to deliberately destabilize it with a timely burst of rocket thrust. After booster burnout, as the model decelerated below Mach 1, the small nose thruster fired, inducing combined yawing, sideslip, and rolling motions. But instead of damping out, the model swiftly went out of control, as if a replay of the XS-1 falling body test 5 years previously. It rolled, pitched, and yawed until it plunged into the Atlantic, its death throes caught by onboard instrumentation and radioed to a NACA ground station. If dry, the summary words of the resulting test report held ominous import for future flight-testing of full-size piloted aircraft: "From the flight time history of a rocket-propelled model of a representative 35° sweptback wing airplane, it is indicated that coupled longitudinal motions were excited and sustained by pure lateral oscillations. The resulting longitudinal motions had twice the frequency of the lateral oscillations and rapidly developed lift loads of appreciable magnitude. The longitudinal moments are attributed to two sources, aerodynamic

In the summer of 1952, as part of an investigation effort studying coupled lateral and longitudinal oscillations, researchers at the NACA’s Pilotless Aircraft Research Division at Wallops Island, VA, fired a series of large rocket-boosted swept wing model airplanes. Spanning over 3 feet, but with a length of nearly 6 feet, they had the general aerodynamic shape of the D-558-2 as originally conceived: with a slightly shorter vertical fin. These models accelerated to supersonic speed and then, after rocket burnout and separation, glided onward while onboard telemetry instrumentation relayed a continuous stream of key performance and behavior parameters as they decelerated through the speed of sound before diving into the sea. On August 6, 1952, technicians launched one equipped with a small pulse rocket to deliberately destabilize it with a timely burst of rocket thrust. After booster burnout, as the model decelerated below Mach 1, the small nose thruster fired, inducing combined yawing, sideslip, and rolling motions. But instead of damping out, the model swiftly went out of control, as if a replay of the XS-1 falling body test 5 years previously. It rolled, pitched, and yawed until it plunged into the Atlantic, its death throes caught by onboard instrumentation and radioed to a NACA ground station. If dry, the summary words of the resulting test report held ominous import for future flight-testing of full-size piloted aircraft: "From the flight time history of a rocket-propelled model of a representative 35° sweptback wing airplane, it is indicated that coupled longitudinal motions were excited and sustained by pure lateral oscillations. The resulting longitudinal motions had twice the frequency of the lateral oscillations and rapidly developed lift loads of appreciable magnitude. The longitudinal moments are attributed to two sources, aerodynamic

moments due to sideslip and inertial cross-coupling. The roll characteristics are indicated to be the predominating influence in the inertial cross-coupling terms.”[73]

![]() Two model tests, 5 years apart, had shown that roll coupling was clearly more than a theoretical possibility. Shortly thereafter it turned into an alarming reality when the Bell X-1A, North American YF-100 Super Sabre, and Douglas X-3 entered flight-testing. Each of these encountered it with varying degrees of severity. The first to do so was the Bell X-1A, a longer, more streamlined, and more powerful derivative of the original XS-1.[74] The X-1A arrived at Edwards in early 1953, flew a brief contractor program, and then entered Air Force evaluation in November. On December 12, 1953, test pilot Charles E. "Chuck” Yeager nearly died when it went out of control at Mach 2.44 at nearly 80,000 feet. In the low dynamic pressure ("low q” in engineering parlance) of the upper atmosphere, a slight engine thrust misalignment likely caused it to begin a slow left roll. As Yeager attempted to control it, the X-1A rolled rapidly to the right, then violently back to the left, tumbling completely out of control and falling over 50,000 feet before the badly battered Yeager managed to regain control. Gliding back to Edwards, he succinctly radioed: "You know, if I’d had a seat, you wouldn’t still see me in this thing.”[75] Afterward, NACA engineers concluded that "lateral stability difficulties were encountered which resulted in uncontrolled rolling motions of the airplane at Mach numbers near 2.0. Analysis indicates that this behavior apparently results from a combination of low directional stability

Two model tests, 5 years apart, had shown that roll coupling was clearly more than a theoretical possibility. Shortly thereafter it turned into an alarming reality when the Bell X-1A, North American YF-100 Super Sabre, and Douglas X-3 entered flight-testing. Each of these encountered it with varying degrees of severity. The first to do so was the Bell X-1A, a longer, more streamlined, and more powerful derivative of the original XS-1.[74] The X-1A arrived at Edwards in early 1953, flew a brief contractor program, and then entered Air Force evaluation in November. On December 12, 1953, test pilot Charles E. "Chuck” Yeager nearly died when it went out of control at Mach 2.44 at nearly 80,000 feet. In the low dynamic pressure ("low q” in engineering parlance) of the upper atmosphere, a slight engine thrust misalignment likely caused it to begin a slow left roll. As Yeager attempted to control it, the X-1A rolled rapidly to the right, then violently back to the left, tumbling completely out of control and falling over 50,000 feet before the badly battered Yeager managed to regain control. Gliding back to Edwards, he succinctly radioed: "You know, if I’d had a seat, you wouldn’t still see me in this thing.”[75] Afterward, NACA engineers concluded that "lateral stability difficulties were encountered which resulted in uncontrolled rolling motions of the airplane at Mach numbers near 2.0. Analysis indicates that this behavior apparently results from a combination of low directional stability

and damping in roll.”[76] The predictions made in Phillips’s 1948 NACA Technical Note had come to life, and even worse would soon follow.

![]() By the time of Yeager’s harrowing X-1A flight, the prototype YF-100, having first flown in May 1953, was well into its flight-test program. North American and the Air Force were moving quickly to fulfill ambitious production plans for this new fighter. Yet all was not well. The prototype Super Sabre had sharply swept wings, a long fuselage, and a small vertical fin. While fighter pilots, entranced by its speed, were enthusiastic about the new plane, Air Force test pilots were far less sanguine, noting its lateral-directional stability was "unsatisfactory throughout the entire combat speed range,” with lateral-directional oscillations showing "no tendency to damp at all.”[77] Even so, in the interest of reducing weight and drag, North American actually shrank the size of the vertical fin for the production F-100A, lowering its height, reducing its area and aspect ratio, and increasing its taper ratio. The changes further cut the directional stability of the F-100A, by some estimates as much as half, over the YF-100.[78] The first production F-100As entered service in the late summer of 1954. Inertial coupling now struck with a vengeance. In October and November, two accidents claimed North American’s chief test pilot, George "Wheaties” Welch, and Royal Air Force Air Commodore Geoffrey Stephenson, commander of Britain’s Central Fighter Establishment. Others followed. The accidents resulted in an immediate grounding while the Air Force, North American, and the NACA crafted complementary research programs to analyze and fix the troubled program.[79]

By the time of Yeager’s harrowing X-1A flight, the prototype YF-100, having first flown in May 1953, was well into its flight-test program. North American and the Air Force were moving quickly to fulfill ambitious production plans for this new fighter. Yet all was not well. The prototype Super Sabre had sharply swept wings, a long fuselage, and a small vertical fin. While fighter pilots, entranced by its speed, were enthusiastic about the new plane, Air Force test pilots were far less sanguine, noting its lateral-directional stability was "unsatisfactory throughout the entire combat speed range,” with lateral-directional oscillations showing "no tendency to damp at all.”[77] Even so, in the interest of reducing weight and drag, North American actually shrank the size of the vertical fin for the production F-100A, lowering its height, reducing its area and aspect ratio, and increasing its taper ratio. The changes further cut the directional stability of the F-100A, by some estimates as much as half, over the YF-100.[78] The first production F-100As entered service in the late summer of 1954. Inertial coupling now struck with a vengeance. In October and November, two accidents claimed North American’s chief test pilot, George "Wheaties” Welch, and Royal Air Force Air Commodore Geoffrey Stephenson, commander of Britain’s Central Fighter Establishment. Others followed. The accidents resulted in an immediate grounding while the Air Force, North American, and the NACA crafted complementary research programs to analyze and fix the troubled program.[79]

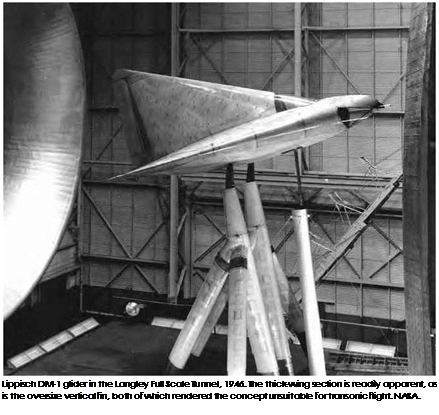

Then, in the midst of the F-100’s travail, inertial coupling struck the Douglas X-3. First flown in October 1952, the X-3 had vestigial straight wings and tail surfaces joined to a missile-like fuselage. Though it was

the most highly streamlined airplane of its time, mediocre engines confounded hopes it might achieve Mach 2 speeds, and it never flew faster than Mach 1.21, and that only in a dive. The NACA acquired it for research in December 1953, following contractor flights and a brief Air Force evaluation. On October 27, 1954, during its 10th NACA flight, test pilot Joseph A. Walker initiated an abrupt left aileron roll at Mach 0.92 at 30,000 feet. The X-3 pitched up as it rolled, sideslipping as well. After it returned to stable flight, Walker initiated another left roll at Mach 1.05. This time, it responded even more violently. Sideslip angle exceeded 21 degrees, and it reached -6.7 g during a pitch-down, immediately pitching up to over 7 g. Fortunately, the wild motions subsided, and Walker, like Yeager before him, returned safely to Earth.[80] With the example of the X – 1A, the F-100A, and the X-3, researchers had conclusive proof of a newly emergent crisis imperiling the practical exploitation of the high-speed frontier.

![]() The F-100A raised the most concern, for it was the first of an entire new class of supersonic fighter aircraft, the "Century series,” with which the United States Air Force and at least some of its allies hoped to reequip. Welch’s F-100A had sideslipped and promptly disintegrated during a diving left roll initiated at Mach 1.5 at 25,000 feet. As Phillips had predicted in 1949, the loads had proven too great for the fin to withstand (afterward, North American engineers "admitted they had been naive in estimating the effects of reducing the aspect ratio and area of the YF-100 prototype tail”).[81] Curing the F-100’s inertial coupling problems took months of extensive NACA and Air Force flight-testing, much of it very high-risk, coupled with analytical studies by Langley personnel using a Reeves Electronic Analogue Computer (REAC), an early form of a digital analyzer. During one roll at Mach 0.7 (and only using two – thirds of available aileron travel), NACA test pilot A. Scott Crossfield experienced "a large yaw divergence accompanied by a violent pitch – down. . . which subjected the airplane to approximately -4.4g vertical acceleration.”[82] Clearly the F-100A needed significant redesign: the Super

The F-100A raised the most concern, for it was the first of an entire new class of supersonic fighter aircraft, the "Century series,” with which the United States Air Force and at least some of its allies hoped to reequip. Welch’s F-100A had sideslipped and promptly disintegrated during a diving left roll initiated at Mach 1.5 at 25,000 feet. As Phillips had predicted in 1949, the loads had proven too great for the fin to withstand (afterward, North American engineers "admitted they had been naive in estimating the effects of reducing the aspect ratio and area of the YF-100 prototype tail”).[81] Curing the F-100’s inertial coupling problems took months of extensive NACA and Air Force flight-testing, much of it very high-risk, coupled with analytical studies by Langley personnel using a Reeves Electronic Analogue Computer (REAC), an early form of a digital analyzer. During one roll at Mach 0.7 (and only using two – thirds of available aileron travel), NACA test pilot A. Scott Crossfield experienced "a large yaw divergence accompanied by a violent pitch – down. . . which subjected the airplane to approximately -4.4g vertical acceleration.”[82] Clearly the F-100A needed significant redesign: the Super

Sabre’s accidents and behavior (and that of the X-3 as well) highlighted that streamlined supersonic aircraft needed greatly increased tail area, coupled with artificial stability and motion damping, to keep sideslip from developing to dangerous values. North American subsequently dramatically increased the size of the F-100’s vertical fin, increased its wingspan by 2 feet (to shift the plane’s center of gravity forward), and incorporated a yaw damper to control sideslip. Though the F-100 subsequently became a reliable fighter-bomber (it flew in American service for almost a quarter century and longer in foreign air arms), it remained one that demanded the constant attention and respect of its pilots.[83]

![]() Inertial coupling was not, of course, a byproduct of conceptualizing the swept and delta wings, nor was it limited (as the experience of the XS-1 falling model, X-1A, and X-3 indicated) just to aircraft possessing swept or delta planforms. Rather, it was a byproduct of the revolution in high-speed flight, reflecting the overall change in the parametric relationship between span and length that characterized aircraft design in the jet age. Low aspect ratio straight wing aircraft like the X-3 and the later Lockheed F-104 were severely constrained by the threat of inertial coupling, even more than many swept wing aircraft were.[84] But for swept wing and delta designers, inertial coupling became a particular challenge they had to resolve, along with pitch-up. As the low-placed horizontal tail reflected the problem of pitch-up, the increasing size of vertical fins (and the addition of ventral fins and strakes as well) incorporated on new aircraft such as the Navy’s F8U-1 and the Air Force’s

Inertial coupling was not, of course, a byproduct of conceptualizing the swept and delta wings, nor was it limited (as the experience of the XS-1 falling model, X-1A, and X-3 indicated) just to aircraft possessing swept or delta planforms. Rather, it was a byproduct of the revolution in high-speed flight, reflecting the overall change in the parametric relationship between span and length that characterized aircraft design in the jet age. Low aspect ratio straight wing aircraft like the X-3 and the later Lockheed F-104 were severely constrained by the threat of inertial coupling, even more than many swept wing aircraft were.[84] But for swept wing and delta designers, inertial coupling became a particular challenge they had to resolve, along with pitch-up. As the low-placed horizontal tail reflected the problem of pitch-up, the increasing size of vertical fins (and the addition of ventral fins and strakes as well) incorporated on new aircraft such as the Navy’s F8U-1 and the Air Force’s

F-105B (and the twin-fins that followed in the 1970s on aircraft such as the F-14A, F-15A, and F/A-18A) spoke to the serious challenge the inertial coupling phenomenon posed to aircraft design. Not visible were such "under the skin” systems as yaw dampers and the strict limitations on abrupt transonic and supersonic rolling taught to pilots transitioning into these and many other first-generation supersonic designs.[85]

![]() The story of the first encounters with inertial coupling is a salutary, cautionary tale. A key model test had resulted in analysis leading to the issuance of a seminal report but one recognized as such only in retrospect. A half decade after the report’s release, pilots died because the significance of the report for future aircraft design and behavior had been missed. Even within the NACA, recognition of seriousness of reduced transonic and supersonic lateral-directional stability had been slow. When, in August 1953, NACA engineers submitted thoughts for a tentative research plan for an F-100A that the Agency would receive, attention focused on longitudinal pitch-up, assessing its handling qualities (particularly its suitability as a gun platform, something seemingly more appropriately done by the Air Force Flight Test Center or the Air Proving Ground at Eglin), and the correlation of flight and wind tunnel measurements.[86] Even after the experience of the X-1A, F-100A, and X-3, even after all the fixes and training, it is disturbing how inertial coupling stilled claimed the unwary.[87] Over time, the combination of refined design, advances in stability augmentation (and eventually the advent of computer-controlled fly-by-wire flight) would largely render

The story of the first encounters with inertial coupling is a salutary, cautionary tale. A key model test had resulted in analysis leading to the issuance of a seminal report but one recognized as such only in retrospect. A half decade after the report’s release, pilots died because the significance of the report for future aircraft design and behavior had been missed. Even within the NACA, recognition of seriousness of reduced transonic and supersonic lateral-directional stability had been slow. When, in August 1953, NACA engineers submitted thoughts for a tentative research plan for an F-100A that the Agency would receive, attention focused on longitudinal pitch-up, assessing its handling qualities (particularly its suitability as a gun platform, something seemingly more appropriately done by the Air Force Flight Test Center or the Air Proving Ground at Eglin), and the correlation of flight and wind tunnel measurements.[86] Even after the experience of the X-1A, F-100A, and X-3, even after all the fixes and training, it is disturbing how inertial coupling stilled claimed the unwary.[87] Over time, the combination of refined design, advances in stability augmentation (and eventually the advent of computer-controlled fly-by-wire flight) would largely render

inertial coupling a curiosity. But for pilots of a certain age—those who remember aircraft such as the X-3, F-100, F-101, F-102, and F-104— the expression "inertial coupling,” like "pitch-up,” will always serve to remind that what is an analytical curiosity in the engineer’s laboratory is a harsh reality in the pilot’s cockpit.