|

|

Int. Designation

|

1993-027A

|

|

Launched

|

26 April 1993

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

6th May 1993

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 22, Edwards AFB, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Columbia/ET-56/SRB BI-057/SSME #1 3031; #2 2109; #3 2029

|

|

Duration

|

9 days 23 hrs 39 min 59 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Columbia

|

|

Objective

|

Operation of the Spacelab D2 research programme located in the Long Module configuration

|

Flight Crew

NAGEL, Steven Ray, 47, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 51-G (1985), STS 61-A (1985); STS-37 (1991) HENRICKS, Terence Thomas “Tom”, 41, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-44 (1991)

ROSS, Jerry Lynn, 45, USAF, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 4th mission

Previous missions: STS 61-B (1985); STS-27 (1988); STS-37 (1991) PRECOURT, Charles Joseph, 37, USAF, mission specialist 2 HARRIS Jr., Bernard Anthony, 36, civilian, mission specialist 3 WALTER, Ulrich, 38, civilian, German payload specialist 1 SCHLEGEL, Hans William, 41, civilian, German payload specialist

Flight Log

Getting STS-55 off the ground proved to be one of the more frustrating tasks of the Shuttle programme. The launch was originally set for late February 1993 but slipped back after problems arose with the turbine blade-tip seal retainers in the high-pressure oxidiser turbo pumps of the SSMEs. The option chosen was to replace the turbopumps at the pad, pushing the launch back to 14 March. This new launch date slipped when a hydraulic flex hose burst during a Flight Readiness Test. All twelve lines were removed and three of them had to be replaced before they could all be reinstalled. The revised 21 March launch was delayed by 24 hours due to a one-day delay in the launch of a preceding Delta II mission. Then, at T — 3 seconds on 22 March, the launch was aborted again by orbiter computers, this time because the #3 engine had failed to ignite. The third pad abort in the programme (the others being STS 41-D in 1984 and STS 51-F in 1985) was later traced to contamination during manufacture that had caused overpressure and precluded full engine ignition. All three engines were

|

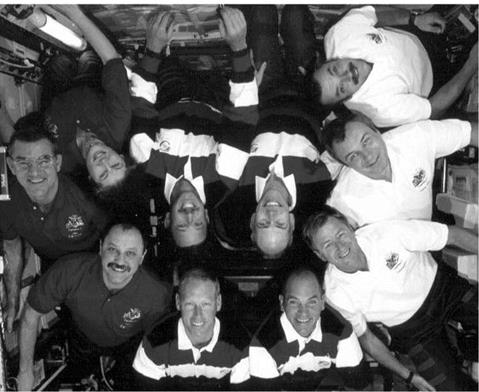

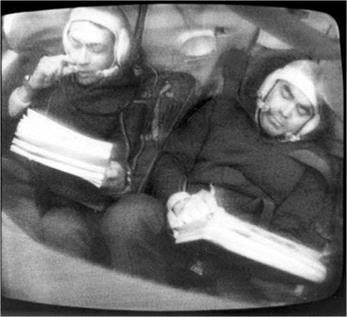

German PS Walter works at the fluid physics experiment in the Spacelab D-2 science module aboard Columbia

|

replaced with spare units. The next attempt, on 24 April, was scrubbed when one of three IMUs gave possibly faulty readings and a 48-hour delay was scheduled to allow the removal and replacement of the IMU. Finally, on 26 April, the launch proceeded without incident. Following the launch, Pad A was scheduled for a period of refurbishment and modification which would last until February 1994.

The second German Spacelab mission featured 88 experiments in materials and life sciences, technology applications, Earth observations, astronomy and atmospheric physics. The crew would work in two shifts. The Red Shift comprised Precourt, Harris and Schlegel, while Nagel, Ross, Henricks and Walter worked the Blue Shift. After all the dramas of getting the mission off the ground, the crew encountered further problems in orbit. An overheating orbiter refrigerator/freezer unit in the mid-deck necessitated the use of a back-up to store samples, while a leaking nitrogen link in the waste water systems had to be fixed by the crew. The mission also suffered from a loss of communications for about 90 minutes due to an errant command from Mission Control in Houston (MCC-H). Columbia flew in a gravity gradient mode for most of the flight, which meant that onboard consumables were used at a reduced level. The mission management team determined that there was sufficient electrical power available to extend the mission by a day, which also meant that at landing Columbia had logged sufficient duration to bring the cumulative total flight time across the fleet (Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour) to 365 days 23 hours 48 minutes – just over one year in space on 55 missions. The landing of STS-55 was originally set for KSC, but was moved to Edwards due to cloud cover over the Shuttle Landing Facility area at the Cape.

Most of the experiments were provided by the German Space Agency and ESA, with a number being supplied by Japan and three by NASA. The French Space Agency, CNES, was also involved in the mission. This was the final “national” Spacelab mission from Germany, due in part to NASA’s reluctance to reduce the costs of flying such a large payload. Germany (and many other nations) decided that in future they would fly their experiments as part of International Spacelab missions. Despite this, valuable experience and information was gathered from the mission that would have relevance to the Columbus module that was being designed by ESA for the US space station (Freedom) programme.

Milestones

160th manned space flight

85th US manned space flight

55th Shuttle mission

14th flight of Columbia

8th Spacelab Long Module mission

2nd dedicated German Spacelab mission

Accumulated flight time for all Shuttles exceeds 1 year

|

Int. Designation

|

1995-030A

|

|

Launched

|

27 June 1995

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

7 July 1995

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-70/SRB BI-072/SSME #1 2028; #2 2034; #3 2032

|

|

Duration

|

9 days 19 hrs 22 min 17 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Atlantis

|

|

Objective

|

1st Mir docking mission; delivery of EO-19 crew; return of EO-18 crew including 1st US NASA Mir resident astronaut (Thagard)

|

Flight Crew

GIBSON, Robert Lee, 48, USN, commander, 5th mission Previous missions: STS 41-B (1984); STS 61-C (1986); STS-27 (1988);

STS-47 (1992)

PRECOURT, Charles Joseph, 39, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-55 (1993)

BAKER, Ellen Louise, 42, civilian, mission specialist 1, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-34 (1989); STS-50 (1992)

HARBAUGH, Gregory Jordan, 39, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-39 (1991); STS-54 (1993)

DUNBAR, Bonnie Jean, 46, civilian, mission specialist 4, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 61-A (1985); STS-32 (1990); STS-50 (1992)

Mir EO-19 crew up only:

SOLOVYOV, Anatoly Yakovlevich, 47, Russian Air Force,

Russian cosmonaut 1, commander EO-19, 4th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM5 (1988); Soyuz TM9 (1990); Soyuz TM15 (1992) BUDARIN, Nikolai Mikhailovich, 42, civilian, Russian cosmonaut 2, flight engineer EO-19

Mir EO-18 crew down only:

DEZHUROV, Vladimir Nikolayevich, 32, Russian Air Force,

Russian cosmonaut 1, commander EO-18

STREKALOV, Gennady Mikhailovich, 54, civilian, Russian cosmonaut 2, flight engineer EO-18, 5th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz T3 (1980); Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10-1 pad abort (1983); Soyuz T11 (1984); Soyuz TM10 (1990)

THAGARD, Norman Earl, 51, civilian, NASA-1 cosmonaut researcher Mir-18, mission specialist 5, 5th mission

Previous missions: STS-7 (1983); STS 51-B (1985); STS-30 (1989); STS-42 (1992)

Flight Log

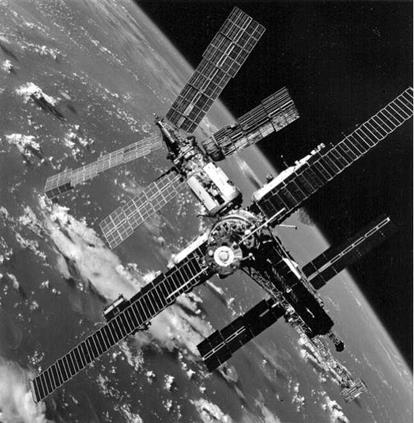

The launch of STS-71 was originally scheduled for late May, but was delayed due to the late launch of Spektr and the series of Mir EVAs in support of relocating the new module. Launch attempts on 23 and 24 June were scrubbed due to weather concerns. The docking with Mir occurred on 29 June, using the Earth radius vector approach (R-Bar) in which the orbiter approached Mir from “below”. The Orbiter Docking System and an Androgynous Peripheral Docking System acted as the connection

|

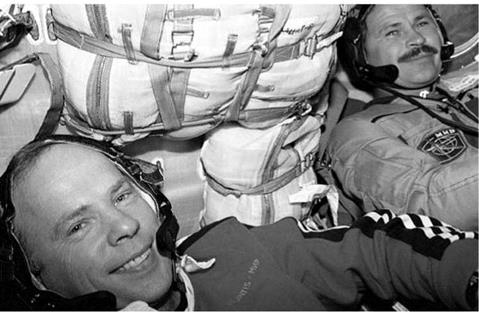

A historic handshake on 29 June 1995 between American astronaut Robert Gibson (STS-71 commander) and Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Dezhurov, Mir-18 commander in the first linkup of a Shuttle and the Mir space complex. This event took place two-and-a-half weeks prior to the 20th anniversary of a similar space greeting, during ASTP in July 1975

|

point between the Shuttle and the Kristall module. The same day, the EO-19 crew took over from the EO-18 crew as residents on the station.

Over the next five days (or 100 hours), a programme of joint biomedical investigations and logistics transfer operations was conducted, the first such activity between US and Russian spacecraft and crews. In the Spacelab module, more than 15 biomedical and scientific investigations were conducted in seven different fields (cardiovascular and pulmonary functions; human metabolism; neuroscience; sanitation and radiation; hygiene; behavioural performance and biology; fundamental biology and microgravity research). Experiment samples from Mir were gathered and returned to Earth aboard Atlantis, including over 100 urine and saliva samples, 30 blood samples, 20 surface samples and 12 air samples. The returning EO-18 crew members also conducted a programme of exercise and prevention measures to help prepare them for the return to Earth after their three-month mission.

Transferred to Mir were 454 kg of water generated by the orbiter system, which would be used on the station for waste system flushing. Specially designed EVA tools were also transferred, as was a supply of oxygen and nitrogen from the Shuttle ECS to raise air pressure inside Mir and conserve the station’s own consumables. A broken Salyut 5-type computer was also returned to Earth aboard Atlantis. Undocking occurred on 3 July, shortly after the EO-19 crew had undocked their Soyuz TM and positioned the small spacecraft to photograph the departure of Atlantis. The Shuttle crew then recorded the re-docking of the Soyuz TM before departing for the return to Earth. The EO-18 crew lay supine in custom-made Russian seat liners to ease their readaptation to gravity due to returning on the Shuttle instead of a Soyuz Descent Module. The complement of eight crew members aboard Atlantis as it came home equalled the largest Shuttle crew in history, STS 61-A in October 1985. The runway was changed from No. 33 to No. 15 just twenty minutes before touchdown, due to concerns over clouds in the area obscuring landing aids.

Milestones

179th manned space flight 99th US manned space flight 69th Shuttle mission 14th flight by OV-104 Atlantis 1st Shuttle-Mir docking

1st space station crew exchange by US Shuttle

100th US human space launch from the Cape in Florida

11th Spacelab Long Module mission

1st and only Spacelab to be part of a Shuttle payload docked to a space station Largest spacecraft ever in orbit (225 tons)

1st on-orbit change of Shuttle crew

Precourt celebrated his 40th birthday in space (29 Jun)

Flight Crew

SOLOVYOV, Anatoly Yakovlevich, 47, Russian Air Force, commander,

4th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM5 (1988); Soyuz TM9 (1990); Soyuz TM15 (1992) BUDARIN, Nikolai Mikhailovich, 42, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

The Mir EO-19 crew arrived at the space station via the American Shuttle during the STS-71 mission. The cosmonauts had received basic training on ascent operations (and emergency escape procedures) at NASA for the ascent to orbit, but it was planned for them to return to Earth in Soyuz TM21, so there was no need for them to conduct extensive Shuttle systems training. The EO-19 crew and their back-ups (Onufriyenko and Usachev) each received on average 70 hours training on Shuttle launch, entry and orbital operations, crew and Shuttle systems, and procedures. The two EO-18 cosmonauts, on the other hand, who would only complete re-entry aboard the Shuttle, received about 28.5 hours each.

After completing the hand-over procedures from the EO-18 cosmonauts, the EO-19 crew transferred their Soyuz seat liners into the Soyuz DM and officially became the resident crew members of the station. On 2 July, the EO-19 cosmonauts undocked their Soyuz TM21 spacecraft from the Kvant module to dock at the forward port, freeing the rear port to receive further Progress re-supply craft. This event also allowed them to photograph the undocking of Atlantis from the station with the returning EO-18 crew. Then the astronauts on Atlantis photographed the re-docking of the Soyuz at the front port of the station before departing to begin the return to Earth.

Safely back on Mir, the two cosmonauts began their short residency, which again was mainly focused on maintenance and repair although they managed to complete

|

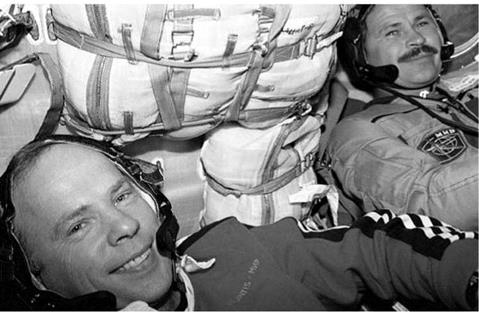

The 19th Mir resident crew consisted of the veteran Solovyov (left) and the rookie Budarin

|

some materials-processing operations. Three EVAs were conducted. The first on 14 July (5 hours 34 minutes) was used to inspect the —Z port where Kristall was to be relocated on 17 July. They found nothing to prevent the relocation, and also used the EVA to unfurl the Spektr arrays using a NASA-provided tool. Solovyov and Budarin also inspected an antenna and a malfunctioning solar array drive motor on the Kvant 2 module. The next EVA on 19 July (3 hours 8 minutes) included the retrieval of a US-provided detector and preparations for installing a joint Belgian/ French/Russian infrared spectrometer. A failed cooling system in Solovyov’s Orlan suit curtailed activities, forcing the cosmonaut to remain near the Kvant 2 hatch and use umbilical cooling supplied from the module instead of the integral backpack. After suit repair work inside Mir, the third EVA on 21 July (5 hours 50 minutes) was used to complete the tasks scheduled for the cancelled second excursion. It was during this EVA that Solovyov became the record-holder for total career EVA time, at 41 hours 49 minutes, surpassing that of Krikalev set in 1992.

Milestones

1st Russian space station crew launched by US Shuttle 1st primary crew flying as passengers on ascent

Flight Crew

HENRICKS, Terence Thomas “Tom”, 43, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-44 (1991); STS-55 (1993)

KREGEL, Kevin Richard, 38, civilian, pilot

THOMAS, Donald Alan, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-65 (1994)

CURRIE, Nancy Jane, 36, US Army, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-57 (1993)

WEBER, Mary Ellen, 32, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

STS-70 should have launched prior to STS-71. However, on 31 May, after northern flicker woodpeckers at Pad 39B had poked approximately 200 holes in the foam insulation of the ET, attempts to repair the damage at the pad were unsuccessful. The resulting rollback to the VAB for repairs forced the mission to be rescheduled after STS-71. The media coverage of the woodpecker activities (from the wildlife nature reserve around the Cape), prompted two JSC employees to design a comic STS-70 mission emblem, adding a smiling Woody Woodpecker cartoon character – a tongue – in-cheek joke that the flight crew enjoyed. They were also amused by the use of the Woody Woodpecker cartoon’s theme tune as a wake-up call on FD 2. The countdown to launch on 13 July proceeded relatively smoothly, with only a short, 55-second hold to verify range safety system signals from the destruct system on the ET. The lift-off marked the shortest time between the landing of one mission and the launch of the next (just 6 days) in the programme. However, post-flight inspection of the right-hand SRM nozzle revealed a gas path in internal joint number 3 that extended from the motor chamber up to, but not beyond, the primary O-ring. A similar gas path had been noted on STS-71 and had been revealed on other missions, but the incidents on STS-71 and STS-70 were the first to show a slight heat effect on the primary O-ring.

|

Tom Henricks on the aft flight deck of Discovery aims towards a site on Earth with the TV camera and other hardware for the HERCULES-B system. For this third-generation space – based geolocation system, a Xybion multispectral camera was integrated with the Hercules geolocation hardware. Previously, a NASA electronic still camera was used on HERCULES-A, flown on STS-53 and STS-56

|

The problem would require investigation and repair on future SRB/SRMs scheduled for flight (see STS-69).

The launch of STS-70 included the first flight of a new Block ISSME (# 2036) that featured improvements to increase the reliability and safety margins of the engines. The first use of three Block I improved engines was scheduled for STS-73. Some six hours into the mission, the crew deployed the final TDRS satellite, which would act as an on-orbit operational spare. With the completion of the primary task, the crew spent the remainder of their mission working on a range of mid-deck experiments.

These focused on plant growth and development, the hormone system of insects, the performance of a bioreactor in microgravity for the growth of individual cells, and a range of experiments aimed at studying the effects of space flight on mammalian development. The crew also conducted commercial protein crystal growth experiments, research into space tissue loss, tests of hand-held space-based geolocation systems, the production of pharmaceuticals in weightlessness, examinations of the effects of ships on the marine environment, radiation monitoring and experiments to understand the chemistry and dynamics of thruster emissions, outgassing and other debris on the Shuttle’s exterior hardware and surfaces.

The mission was also to be run from the new upgraded Mission Control Room in Building 30 at the JSC facility near Houston, Texas. Following the deployment of TDRS, the controllers on the next shift operated from the new MCC (called the White Flight Control Room – FCR, pronounced “flicker”). The old room had been used since Gemini 4 in June 1965 and became famous as the Apollo mission control room during the lunar landing missions. It would be turned into a national monument and tourist attraction at JSC. Orbital operations continued in the new room, but landing operations were handled from the old room. Until early 1996, all Shuttle launch and landing phases would still be controlled from the old FCR, but would gradually be moved into the new room.

The first landing opportunity for STS-70, on 21 July at KSC, was waived off due to fog and low visibility, as was the first attempt on 22 July. Following the landing, Discovery was prepared for shipment to California for a period of refurbishment and modifications. It was due to return to duty in the summer of 1996, to prepare for the second Hubble service mission planned for early 1997 (STS-82).

Milestones

180th manned space flight

100th US manned space flight

70th Shuttle mission

21st flight of Discovery

7th and final TDRS deployment mission

1st use of new MCC in Houston, JSC

Quickest turnaround from landing (STS-71) to launch (STS-70) between missions – 6 days

2001-035A

2001-035A