STS-33

|

Int. Designation |

1989-090A |

|

Launched |

22 November 1989 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

27 November 1989 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 04, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET-38/SRB BI-034/SSME #1 2011; |

|

#2 2031; #3 2107 |

|

|

Duration |

5 days 0 hrs 6 min 48 sec |

|

Callsign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

5th classified DoD Shuttle mission |

Flight Crew

GREGORY, Frederick Drew, 48, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 51-B (1985)

BFAHA, John Elmer, 47, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-29 (1989)

CARTER Jr., Manley Fanier “Sonny”, 42, USN, mission specialist 1 MUSGRAVE, Franklin Story, 54, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-6 (1983); STS 51-F (1985)

THORNTON, Kathryn Cordell Ryan, 37, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

With STS-33 flying after STS-34 but before STS-32, it was understandably difficult to keep track of how many Space Shuttles had been launched by November 1989. STS-33 Discovery was the thirty-second Space Shuttle mission but only the thirty-first to reach space. It was due to launch in August 1989 but had to make way for the delayed STS-28 and for the STS-34 planetary launch window. It was also the first Shuttle to fly with a crewman replacing one who had died. Pilot David Griggs had been killed in the crash of an aerobatics plane in June 1989 and was replaced on the mission by John Blaha, recently returned from STS-29, who was thus making a second flight in a record seven months.

The mission was unusual in that while it was a classified military affair, it carried two civilian crew persons, mission specialists Kathryn Thornton on her first flight, and the veteran Story Musgrave on his third (though both had previous experience in classified roles. Thornton had worked with the Army Foreign Science and Technology Center before being selected for astronaut training and Musgrave had served in the USMC in the 1950s). The fact that the third mission specialist, Manley Carter, was a doctor like Musgrave and that Thornton was a nuclear physicist indicated that several biomedical-radiation crew experiments were on the schedule after the deployment of

|

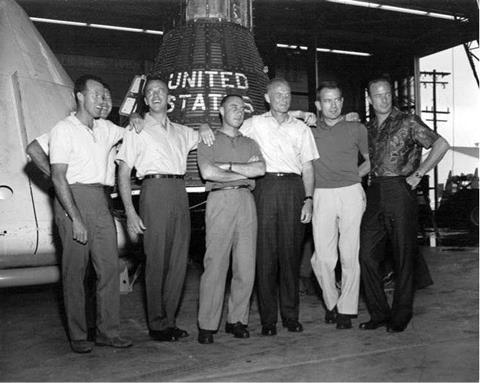

Carter and Thornton display a slogan for Astronaut Group 10, “The Maggots”. This was the unofficial nickname for the group which came from their self-professed love of food |

the main payload. This was a SIGINT electronic signals intelligence satellite, ELINT, deployed in the 28° inclination, 561 km (249 miles) apogee orbit.

Discovery was raring to go on the first attempt and was held for just 90 seconds at T — 5 minutes before making a spectacular departure from Pad 39B at 19: 23 hrs local time, turning night into day and the quiet peace of the Cape’s lagoons into a frightening cacophony. The SIGINT was deployed on orbit seven. The flight was due to last four days but was extended for almost a day by excessive winds at Edwards, where it was to have made the first night landing since the Challenger accident. Discovery was waived off again by one orbit and after its long re-entry from high orbit was diverted from the concrete runway to runway 04 at Edwards, landing at T + 5 days 0 hours 6 minutes 48 seconds.

Milestones

129th manned space flight 62nd US manned space flight

1st military manned flight with “civilian” and female crew

32nd Shuttle mission

9th flight of Discovery

5th classified DoD Shuttle mission

. SOYUZ TM14Flight Crew VIKTORENKO, Alexandr Stepanovich, 44, Russian Air Force, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz TM3 (1987), Soyuz TM8 (1989) KALERI, Alexandr Yuriyevich, 35, civilian, flight engineer FLADE, Klaus-Dietrich, 39, German Air Force, cosmonaut researcher Flight Log The fully automated docking of TM14 to Mir was final confirmation that the Kurs rendezvous system had been repaired. After being bumped off the crew for TM13, Kaleri finally made it to Mir, alongside German cosmonaut Klaus Flade who conducted fourteen German experiments during his week aboard the station. His programme included materials processing experiments and Flade would also provide baseline biomedical data in preparation for extended orbital operations on the ESA Columbus laboratory, part of the Freedom Space Station programme. He would return to Earth with Volkov and Krikalev in the TM13 spacecraft, after they had spent the week briefing the new resident crew and packing their equipment for the return to Earth. At this time, there was a strong possibility that the cash-starved Russian Space Agency might be forced to temporarily abandon Mir until new funds could be secured to support further manned operations. The EO-11 crew were therefore never sure when they might be called back to Earth. This residency was also very “quiet”, with the cosmonauts continuing the on-going programme of Earth observations, materials processing, biomedical studies and astrophysical observations, balanced with routine maintenance, housekeeping and unloading the Progress supply vehicles. The docking of Progress M13 was aborted on 2 July due to a fault in the onboard software, but

reprogramming by operators on the ground resolved the problem, allowing a safe docking two days later to deliver some of the experiments for the upcoming French mission. On 8 July, the crew performed the only EVA of their residency (of 2 hours 3 minutes) to examine the gyrodynes on the outside of Kvant 2. A dozen gyrodynes stabilised the station as it orbited the Earth. Similar to gyroscopes, these spinning devices generated angular momentum to maintain Mir’s orientation to the Sun, which was essential for the solar arrays to be able to absorb energy to produce electricity for use on the station. Though the gyrodynes consumed considerable power to start with, once they were spinning, they would run for some time with minimal energy consumption. Five of the six units on Kvant 1 had exceeded their five-year design life but four of the six on Kvant 2 had failed. During this EVA, the cosmonauts wielded large shears to cut through thermal insulation on Kvant 2 to reach the gyrodynes and inspected and photographed the units for engineers back on the ground as part of an evaluation for future EVA operations to remove and replace them. The cosmonauts also evaluated binoculars that were compatible with the Orlan suit’s visor to allow inspection of the more remote areas of Mir, where it would be difficult, if not impossible, for a cosmonaut to get to. This was a quiet tour of duty on the space station. The two cosmonauts completed a programme of agricultural photography and spectral observation before dividing their time between these commitments and their astrophysical observations. As the crew completed these studies, the onboard furnaces were being run in semiautomated mode. Towards the end of their residency the crew received the EO-12 cosmonauts and French cosmonaut researcher Michel Tognini, who would complete his own research programme during a 12-day hand-over period, and return with the EO-11 cosmonauts. Milestones 148th manned space flight 73rd Russian manned space flight 21st Russian and 45th flight with EVA operations 14th Soyuz flight to Mir 11th main Mir crew 9th visiting crew (Flade) 66th Soyuz manned mission 13th Soyuz TM manned mission Viktorenko celebrates his 45th birthday in space (29 Mar) Kaleri celebrates his 36th birthday in space (13 May)

Flight Crew BLAHA, John Elmer, 51, USAF, commander. 4th mission Previous missions: STS-29 (1989); STS-33 (1989); STS-43 (1991) SEARFOSS, Richard Alan, 37, USAF, pilot SEDDON, Margaret Rhea, 45, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-D (1985); STS-40 (1991) McARTHUR Jr., William Surles, 42, US Army, mission specialist 2 WOLF, David Alexander, 37, civilian, mission specialist 3 LUCID, Shannon Wells, 50, civilian, mission specialist 4, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 51-G (1985); STS-34 (1989); STS-43 (1991) FETTMAN, Martin Joseph, 36, civilian, payload specialist 1 Flight Log The first attempt at launching STS-58 on 14 October was scrubbed at the T — 31 second mark, as a result of a failed range safety computer. The next attempt on 15 October was scrubbed at T — 9 minutes due to a failed S-band transponder aboard Columbia. The launch on 18 October was also delayed, but only by a few seconds due to an aircraft straying into the launch exclusion zone. Over the next 14 days, the crew, working a single-shift system, conducted the SLS – 2 research programme and other research objectives, including the Orbiter Acceleration Research Experiments, SAREX, and Pilot In-flight Landing Operations Trainer (PILOT), a portable laptop computer simulator that allowed the commander and the pilot to maintain their proficiency for approach and landing on longer missions. The SLS payload included 14 experiments focusing on four areas: regular physiology, cardiovascular/cardiopulmonary, musculoskeletal and neuro-science experiments. The Rotating Dome Experiment was used in conjunction with the first

flight prototype of the Astronaut Science Advisor (ASA), a laptop computer program designed to assist the crew member in conducting experiments to increase the efficiency of activities. This was also termed the “principle investigator in a box”. Of the fourteen experiments, eight focused on the astronauts, while the other six were conducted on the 48 rodents aboard. Six of the rodents were killed and dissected during the mission, yielding the first tissue samples collected during a space mission which were not altered by re-exposure to the Earth’s gravity. During the mission, the crew collected over 650 different samples from the rodents and themselves. This greatly increased the database of life science research and this work continued, at least for the “payload crew’’ (Seddon, Fettman, Lucid and Wolf) after landing. For the first week after the end of the mission, these four astronauts gave regular blood and urine samples to reveal how the body readjusted to gravity after two weeks in space. The blood samples were collected over a period of 45 days after landing. The combined data from SLS-1 and SLS-2 helped to build a more comprehensive picture of how animals and humans adapted to space flight and readapted to life back on Earth, an important milestone in developing protocols and research programmes for the space station. There were plans to fly a third SLS, which could have become a dedicated French Spacelab mission, but this was not pursued due to budget restrictions, launch manifest constraints and the introduction of the Shuttle- Mir programme, which drew resources away from Spacelab missions. Milestones 164th manned space flight 88th US manned space flight 58th Shuttle mission 15th flight of Columbia 2nd flight of SLS series 9th Spacelab Long Module mission Longest Shuttle mission to date 4th longest US spaceflight (after three Skylab missions) 1st veterinarian to fly in space (Fettman) 1st tissue samples collected during a space flight (rodents)

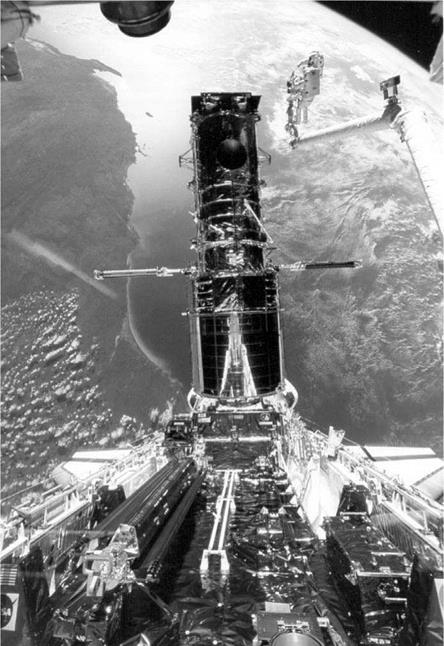

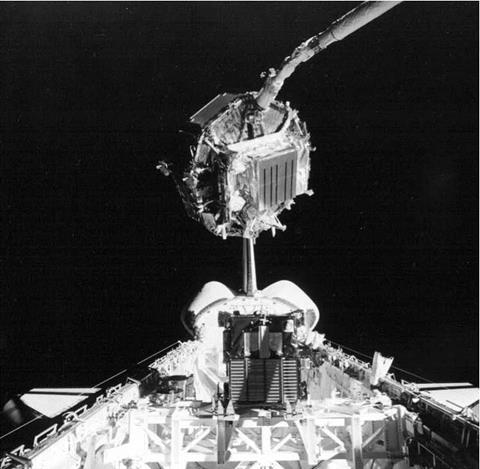

Flight Crew COVEY, Richard Oswalt, 47, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 51-I (1985); STS-26 (1988); STS-38 (1990) BOWERSOX, Kenneth Duane, 37, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-50 (1992) THORNTON, Kathryn Cordell Ryan, 41, civilian, mission specialist 1, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-33 (1989); STS-49 (1992) NICOLLIER, Claude, 49, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-46 (1992) HOFFMAN, Jeffery Alan, 49, civilian, mission specialist 3, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 51-D (1985); STS-35 (1990); STS-46 (1992) MUSGRAVE, Franklin Story, 58, civilian, mission specialist 4, payload commander, 5th mission Previous missions: STS-6 (1983); STS 51-F (1985); STS-33 (1989); STS-44 (1991) AKERS, Thomas Dale, 42, USAF, mission specialist 5, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-41 (1990); STS-49 (1992) Flight Log Described as one of the most challenging manned missions ever attempted, the crew of STS-61 completed a record-breaking five back-to-back EVAs during the first on – orbit service of the Hubble Space Telescope. Many of their tasks were completed sooner than expected, allowing the few contingencies that did occur to be dealt with smoothly. The original launch was to have occurred from Pad 39A at KSC, but following the rollout of the stack to the pad, contamination was discovered in the payload change-out room. As a result, the STS-61 launch was moved to Pad B.

At an altitude of 522 km above the Earth, Musgrave (top) and Hoffman are seen riding on the RMS during the fifth and final EVA of the mission to service the Hubble Telescope, one of the most successful space missions to date. The west coast of Australia forms the backdrop to the scene The move occurred without incident on 15 November but the first launch attempt on 1 December was scrubbed due to adverse weather conditions at the SLF. A series of service missions had always been part of the HST programme. At regular intervals, a Shuttle would be sent to repair, replace or upgrade onboard instruments, equipment or systems prolonging the operational life of the facility and improving the quality and quantity of scientific discoveries over the planned fifteen – year life of the telescope. With the focusing difficulties encountered shortly after deployment from STS-31 in 1990, some media reports incorrectly labelled this flight as rescue mission, specially organised to save the telescope. The mission did restore the telescope to full working order, but the corrective optics were incorporated into a far more extensive, and already planned, servicing operation. Rendezvous with Hubble was achieved on FD 3, with the RMS grapple and berthing in the payload bay completed the same day. The telescope was berthed upright in the payload bay of the Shuttle, but remained under the command of the Space Telescope Operations Control Center (STOCC) located at the Goddard Space Flight Center. Following each servicing task, the STOCC controllers verified the interfaces between the new or serviced hardware and the telescope, ensuring at each stage that the telescope would be capable of independent operations once released from the payload bay. Over a five-day period (4-8 December), the EVA team of four astronauts worked in pairs to complete the complex and demanding programme to restore the telescope to full working order. During the first EVA, four gyros that were situated in pairs in two Rate Sensing Units were replaced, along with two Electronic Control Units that directed the RSUs and eight electrical fuse plugs. The first EVA (7 hours 54 minutes on 4 Dec, conducted by Hoffman (EV1) and Musgrave (EV2)) was the second longest in the US programme to date and the only problem encountered was difficulty in closing the compartment doors after replacing the RSUs. During the next EVA (6 hours 36 minutes on 5 Dec, conducted by Thornton (EV3) and Akers (EV4)), one of the primary objectives of the servicing mission was completed, that of installing new solar arrays. The old arrays were scheduled to be returned to Earth for examination after over three years in space, but one of them refused to fully retract due to a kink in the framework and had to be jettisoned. The other was stowed in the payload bay without difficulty. The third EVA (6 hours 47 minutes on 6 Dec, the second for Hoffman and Musgrave) was designed to replace the Wide Field/Planetary Camera (WF/PC), one of the five scientific instruments on the telescope, in a four-hour operation. In fact, the astronauts accomplished the exchange with the improved WF/PCII (an upgraded spare modified to compensate for the flawed mirror) in just forty minutes. Two magnetometers were also installed in the top of the telescope. EVA 4 (6 hours 50 minutes on 7 Dec, the second for Thornton and Akers) included the replacement of another primary instrument, the High-Speed Photometer, with the Corrective Optics for Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR) unit – often dubbed Hubble’s “spectacles” – which redirected light to three of the four remaining instruments, thus compensating for the flaw in the primary mirror. The astronauts also installed a co-processor that improved the memory and speed of the onboard computer. During this EVA, Tom Akers achieved a new cumulative record for an American astronaut on EVA (29 hours 39 minutes), surpassing the 20-year-old record set by Gene Cernan on Apollo 17 at 24 hours 14 minutes. Kathy Thornton became the record-holder for female EVA astronauts at 21 hours 10 minutes. Both had performed EVAs on STS-49 in 1992. During the final EVA (7 hours 21 minutes on 9 Dec, the third by Hoffman and Musgrave), the astronauts replaced the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) unit, as well as installing the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph Redundancy (GHRS) equipment and placing two protective covers over the original magnetometer. During FD 8, prior to the final EVA, the Shuttle’s orbit was boosted to 595 km. At this height, the telescope would be released on FD 9, after deployment of the twin boom antennas, unfurling of solar arrays and checking of onboard systems. The redeployment was delayed several hours when ground controllers had to troubleshoot erratic telemetric data from the telescope’s systems monitor. This had occurred before and was not connected to the recent servicing by the astronauts. The mission ended one orbit earlier than planned to allow the crew two landing opportunities at KSC. Milestones 165th manned space flight 89th US manned space flight 59th Shuttle mission 5th flight of Endeavour 1st Hubble servicing mission 29th US and 53rd flight with EVA operations 1st flight of ESA astronaut as MS2 US astronaut cumulative EVA record – Akers World female cumulative EVA record – Thornton STS-72

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 20 January 1996 Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida OV-105 Endeavour/ET-75/SRB BI-077/SSME #1 2028; #2 2039; #3 2036 8 days 22 hrs 1 min 47 sec Endeavour Retrieval of Japanese Space Flyer Unit; deployment and retrieval of OAST-Flyer; EDFT-03 Flight Crew DUFFY, Brian, 42, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-45 (1992); STS-57 (1993) JETT Jr., Brent Ward, 37, USN, pilot CHIAO, Leroy, 35, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-65 (1994) SCOTT, Winston Elliott, 45, USN, mission specialist 2 WAKATA, Koichi, 32, civilian, Japanese mission specialist 3 BARRY, Daniel Thomas, 42, civilian, mission specialist 4 Flight Log The launch of STS-72 was delayed for 23 minutes due both to problems with ground sites and the need to avoid a potential collision with an item of space debris. On FD 3, Japanese MS Wakata used the RMS to grasp the Japanese Space Flyer Unit (SFU), which had originally been launched in March 1995 aboard an H-2 rocket from the Tanegashima Space Centre in Japan. Over a ten-month period, more than a dozen onboard instruments and experiments had been operating in a research programme that encompassed materials and biological science. Prior to grappling the unit with the RMS, the twin solar arrays had to be jettisoned after it was found that they were not correctly retracted. The next day, the Office of Aeronautics and Space Technology Flyer (OAST – Flyer) was deployed, again by Wakata using the RMS, on an independent two-day flight that extended to approximately 72 km from Endeavour. Attached to the SPARTAN platform were four experiments that investigated spacecraft contamination, global positioning technology, laser ordnance devices and an amateur radio package. The flyer was retrieved on FD 6. In addition to the deployment and retrieval operations, the crew had a programme of payload bay and mid-deck secondary

experiments to conduct, which mainly consisted of studies in ozone concentrations in the atmosphere, a laser to accurately measure the distance between the Earth’s surface and the orbiter, and a range of biological and biomedical experiments. The crew also completed two EVAs as part of the EDFT programme of preparation for extensive EVA activities during ISS construction. During the first EVA (15 Jan, 6 hours 9 minutes), astronauts Chiao (EV1) and Barry (EV2) evaluated a new portable work platform and the Rigid Umbilical Structure, which was being developed as a possible retention device for ISS fluid and electrical lines. During the second EVA (17 Jan, 6 hours 54 minutes), this time conducted by Chiao and Scott (EV3), the portable work platform was again evaluated and the astronauts also tested the design of a utility box, another item under development for ISS, which would hold avionics and fluid line connections. During the EVA, Scott tested his suit in severe cold temperatures of up to —75°C, to find out whether the revised design would keep him warm during the test. In fact, the 35-minute test resulted in temperatures of — 122°C being recorded, providing a tough test of the suit’s extremities (fingers and feet) and coolant loop bypass system. Scott reported that he was aware of the low temperatures but remained comfortable and though had he been working rather than staying still, he determined that he would have felt warmer in either situation. Milestones 185th manned space flight 104th US manned space flight 74th Shuttle mission 10th flight of Endeavour 33rd US and 60th flight with EVA operations 3rd EDFT exercise . SOYUZ TM28Flight Crew PADALKA, Gennady Ivanovich, 40, Russian Air Force, commander AVDEYEV, Sergei Vasilyevich, 42, civilian, flight engineer, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz TM15 (1992); Soyuz TM22 (1996) BATURIN, Yuri Mikhailovich, 49, Russian Air Force, cosmonaut researcher Flight Log Before becoming a cosmonaut, Yuri Baturin had been a space physicist. He then became the national security advisor for President Boris Yeltsin and then the Defence Council Secretary. He was also an advisor on space matters and was attached to the 1997 Air Force cosmonaut selection (with the rank of colonel). In April 1998, he completed a 12-day mission to Mir, returning with the EO-25 crew. After his mission he stated that, in his opinion, the Mir complex should be kept operating for at least two years beyond the planned 1999 decommission date. When Baturin and the E0-25 crew departed Mir, the two remaining cosmonauts pursued their EO-26 programme. This included an internal EVA inside the forward node to reset electrical connectors inside the Spektr module. Their subsequent 10 November EVA (5 hours 54 minutes) featured the deployment of Japanese and French experiments. They then continued their programme of experiments, many of which had been left on board the station by international visitors, enhancing the return from the investment in those experiments. Mir was almost forgotten in the wake of the launch of the first element of ISS – the Zarya module – in November. This was followed by the first Shuttle mission to add other elements – the US node Unity – the following month. With ISS in orbit, Russia indicated that it was looking for private funds to keep Mir aloft into the new

millennium, as governmental support would end in 1999 when its commitment to ISS increased. When news came that the Service Module of the new station (Zvezda) would be delayed into 2000 and with it the capability of supporting a resident crew, the call to maintain Mir operations beyond 1999 intensified. There was also discussion about further commercial ventures for the station, including filming part of a movie aboard Mir with actors making a short visiting mission to film scenes in orbit. With news that a new investor might support further use of Mir, there remained the question of fitting in the two missions already planned as the EO-26 residence drew to a close and Mir funding from the government ended. The two options were to either fly a Russian commander with the French flight engineer to see out the planned programme, or to leave Avdeyev aboard Mir to join the Russian and French crew members, making a three-person crew for the remainder of the government-funded occupation of the station. The subsequent Slovak mission could then be launched with the new crew and return with Padalka on TM28. In the new year, the cosmonauts continued their science programme as news came in that the life of the station was to be extended three years (to 2002), if sufficient nonbudgetary (government) funds could be found. This allowed Energiya to tentatively plan a programme through to 2001. Just weeks later, the news came that the “private investor” had pulled out. The EO-27 crew launched in February 1999 were expecting to be the last crew to man the station. Milestones 208th manned space flight 87th Russian manned space flight 80th manned Soyuz mission 27th manned Soyuz TM mission 26th Mir resident crew 33rd Russian and 71st flight with EVA operations Avdeyev celebrates his 43rd birthday (1 Jan) on Mir – the third birthday he has spent in space (previously 1993 and 1996)

Flight Crew BROWN Jr., Curtis Lee, 46, USAF, commander, 5th mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-66 (1994); STS-77 (1996); STS-85 (1997) LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 38, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-87 (1997) ROBINSON, Stephen Kern, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-85 (1997) PARAZYNSKI, Scott Edward, 37, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-66 (1994); STS-86 (1997) DUQUE, Pedro Francisco, 35, civilian, mission specialist 3 MUKAI, Chiaki, 46, civilian, payload specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-65 (1994) GLENN Jr., John Herschel, 77, US Senator, payload specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: Mercury 6 (1962) Flight Log John Glenn, the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth in 1962, had always wanted to return to space. But he had not expected that it would take over 36 years for him to do so. While pursing a business and political career, Glenn had always maintained a close relationship with NASA and had convinced NASA administrators that a set of medical experiments looking at the effects of microgravity on an older person would be of benefit to the near – and long-term goals of the agency. It would also provide an interesting set of comparison data with that taken during his first flight in 1962. Glenn first approached NASA with the idea in 1996, but it took two years to develop the experiment programme and obtain formal authorisation. The flight was also a public relations triumph for the space agency and a swansong of Glenn’s career in public life.

US Senator and former Mercury astronaut John H. Glenn Jr., equipped with sleep-monitoring equipment, floats near his sleep station on the mid-deck of Discovery The launch progressed smoothly, with only minimal delays caused by a master alarm in the cabin and an aircraft infringement in the restricted airspace around KSC. After the ignition of the three main engines and prior to SRB ignition, the drag chute compartment door fell off, but this never posed a problem for the mission. It was decided that the drag chute would not be deployed during landing rollout. The primary objective of the flight was a suite of over 80 experiments in the SpaceHab module. These focused on medical and materials research and a series of life sciences investigations that were sponsored by NASA and the space agencies of Canada, Europe and Japan (hence the inclusion of Duque and Mukai on the crew). The latter included cardiovascular studies, sleep studies and blood research. The investigations conducted by and on John Glenn provided useful data that would help to understand the process of aging in humans. The aging process and long space flights have similar common physiological effects and it was felt that information from Glenn and the other astronauts would help not only with long-duration space flight countermeasures, but also to identify early signs of aging and deterioration, which would assist in understanding the process and help in the development of countermeasures for the aging process on Earth. Like all former NASA astronauts, Glenn had been undertaking regular annual physicals at JSC since leaving the programme. These examinations have built up into an impressive database of biomedical studies of space explorers to see what changes, if any, occur as a result of space flight. Glenn’s flight at the age of 77, some 36 years after his first flight, was a unique opportunity to expand this data base. His experiments focused on how the absence of gravity affects balance and perception, the immune system response, bone and muscle density, metabolism and blood flow, and sleep. The flight also included a range of studies on fish and plant specimens and a programme of microgravity materials studies in agriculture, medicine and manufacturing. During the mission, the crew also released a Petite Amateur Naval Satellite (PANSAT), which tested innovative technologies to capture and transmit radio signals normally lost because the original signal was too weak. The Hubble Space Telescope Orbital System Test provided an on-orbit test bed for hardware that would be used during the third Hubble service mission in 1999. The SPARTAN 201 free-flyer was released between FD 4 and 6, carrying a set of re-flight experiments from the 1997 STS-87 mission, with instruments to study the solar corona and gather data on the solar wind. Also located in the payload bay was a Hitchhiker Support Structure (HSS) with six experiments which had solar, terrestrial and astronomical objectives, to obtain data on extreme UV radiation on the sun and atmosphere. A UV spectrograph telescope was included to obtain information on extended plasma sources, such as hot stars and the planet Jupiter. There were concerns over Glenn’s health on both his missions, the first because he was venturing into the unknown and the second over his age. But he had maintained a fine physical condition throughout his life. Upon entering space in 1962, Glenn commented: “Zero-G and I feel fine,’’ and 36 years later he said that he still felt the same way. When he returned to Earth at the end of STS-95, his comment was: “One-G and I feel fine.’’ Milestones 209th manned space flight 122nd US manned space flight 92nd Shuttle flight 25th flight of Discovery 12th SpaceHab mission (7th single module) 1st flight of SSME Block II engines Glenn becomes oldest person to fly in space, aged 77

Flight Crew ONUFRIYENKO, Yuri Ivanovich, 40, Russian Air Force, ISS-4 and Soyuz TM commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM23 (1996) BURSCH, Daniel Wheeler, 44, USN, ISS-4 flight engineer 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-68 (1994); STS-77 (1996) WALZ, Carl Erwin, 46, USAF, ISS-4 flight engineer 2, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-65 (1994); STS-79 (1996) Flight Log The fourth expedition featured an experiment programme of 26 US and 28 Russian experiments in the fields of bioastronautics research, physical sciences, space product development, fundamental space biology, Earth observations, education and technology. Many of these experiments were carried over from previous expeditions. During their stay aboard the station, the crew performed three EVAs. The first two (14 Jan for 6 hours 3 minutes and 25 Jan for 5 hours 59 minutes) were conducted from the Pirs facility on the Russian segment. The final one (20 Feb for 5 hours 47 minutes) was conducted out of the Quest airlock on the American segment. During the first EVA, Onufriyenko and Walz relocated the cargo boom for the Strela crane from PMA-1 to the outside of Pirs. An amateur radio antenna was also installed on Zvezda. EVA-2 saw Onufriyenko and Bursch install six deflector shields on the Service Module thrusters, install a further antenna and retrieve various science packages from Zvezda. The final EVA was conducted by the two American members of the ISS-4 crew on the 40th anniversary of the first flight of John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. Walz and Bursch performed the EVA from the Quest airlock, the first without a docked Shuttle in support. The objective was to prepare the area for installation of the S0 Truss during STS-110 in April 2002, relocating the tools to be used and inspecting the exterior of the station.

During the mission, the crew would oversee the upgrading of software as well as receiving the Progress Ml-8 re-supply craft. Their visitors arrived on the STS-110 mission that delivered the S0 Truss assembly and on the Soyuz TM33 Taxi mission. Prior to the arrival of Soyuz TM34, the crew had to relocate TM33 from the nadir port of Zarya to redock with the Pirs docking port. The crew experienced several power problems and a number of failures of the Elektron oxygen generator. To conserve oxygen reserves in the tanks of Quest, the crew resorted to burning solid fuel oxygen generators in the Zvezda module while they attempted repairs to Elektron. This took several days during May. They also experienced difficulties with the operation of the Canadarm2, including the failure of the wrist roll joint, which would require replacement. They were relieved on the station in June by the ISS-5, who arrived on STS-111, the mission that would take the ISS-4 crew back to Earth. Both the Americans in the ISS-4 crew surpassed Shannon Lucid’s previous US space flight endurance record (188 days), eventually clocking 196 days. In their careers, both men had flown four times and by the end of their ISS mission, Walz had logged 231 days in space while Bursch had accumulated 227 days. Onufriyenko had also completed two long missions and brought his experience to 389 days by the end of this one. Milestones 4th ISS resident crew 3rd ISS EO crew to be launched by Shuttle 1st EVA from Quest without a Shuttle docked to the station

Flight Crew LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 45, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-87 (1997); STS-98 (1998); STS-104 (2001) KELLY, Mark Edward, 42, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-108 (2001) FOSSUM, Michael Edward, 48, civilian, mission specialist 1 NOWAK, Lisa Marie, 43, USN, mission specialist 2 WILSON, Stephanie Diana, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3 SELLERS, Piers John, 51, civilian, mission specialist 4, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-112 (2002) ISS-13 crewmember up only: REITER, Thomas, 48, German Air Force, ESA mission specialist 5, ISS-13 flight engineer 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM22 (1995) Flight Log Bad weather again delayed the launch of the Shuttle on 1 and 2 July, but after a one – day stand down, the launch resumed and STS-121 lifted off on America’s 230th birthday, the first launch on Independence Day, Again the launch phase was dramatically caught on film and analysed for any serious debris impacts, Though some debris hits were noted, there were no serious impacts, Following the docking on 6 July, the crew relocated the Leonardo MPLM to the station, where 3,357 kg of logistics was transferred. This included a new heat exchanger, a new window and window seals for the Microgravity Science Glove Box, a US EMU suit, SAFER jet pack and personal items, and a new oxygen generator to be installed in Destiny, There was also a

European Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for storage of experiment samples prior to return to Earth. The MPLM was relocated back in the payload bay of Discovery on 14 July, by which time it had been filled with 2,086 kg of experiment samples, broken equipment and trash. Three EVAs by Sellers (EV1) and Fossum (EV2) were completed during the docked phase of the flight. EVA 1 (8 Jul for 7 hours 31 minutes) included fitting a protection device for power, data and video cables on the S0 Truss. By routing cables through the Interface Umbilical Assembly, they could move the MT railcar to replace the trailing umbilical system with its power and data cable that had been inadvertently severed late in 2005. The astronauts then evaluated the RMS with the Orbiter Boom Sensor System, for potential use as a work platform during EVA to repair the damaged orbiter if required. EVA 2 (10 Jul for 6 hours 47 minutes) saw the crew restore the MT to full operation, while EVA 3 (12 Jul for 7 hours 11 minutes) focused on testing repairs on the Thermal Protection System Reinforced Carbon-Carbon panels, part of the evaluation of repair techniques that may be available to effect orbital repairs on future Shuttle missions. Photography of the samples (together with that of an area of Discovery’s port wing) was conducted. These images would be returned to Earth for detailed analysis. The astronauts also relocated a fixed grapple bar on the integrated cargo carrier in the payload bay to a position on the ammonia tank inside the SI Truss assembly, so that it could be moved by a future EVA crew at a later date. Thomas Reiter had formerly exchanged to the ISS-13 crew shortly after the hatches between the vehicles had opened, moving his Soyuz seat liner into the DM of Soyuz TMA8. The more formal farewells occurred shortly prior to closure of the hatches and undocking of the Shuttle on 15 July. The two spacecraft had been docked for over 9 days, a day longer than planned as the mission was extended by a day to accommodate the third EVA. A final check of the surfaces of Discovery revealed nothing of concern and the safe re-entry and landing two days later gave an added boost to mission planners, eager to resume station construction with the next Shuttle mission. Milestones 248th manned space flight 145th US manned space flight 115th Shuttle mission 32nd flight of Discovery 18th Shuttle ISS flight 58th US and 97th flight with EVA operations 6th Discovery ISS mission 7th MPLM flight 4th flight of MPLM-1 Leonardo 1st US launch on 4 July

|

1996-001A 11 January 1996

1996-001A 11 January 1996

1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962

1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962