1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

11 (Soyuz 6), 12 (Soyuz 7) and 13 (Soyuz 8) October 1969 Pad 1, Site 5 (Soyuz 7); Pad 31, Site 6 (Soyuz 6, Soyuz 8), Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan 16 (Soyuz 6), 17 (Soyuz 7) and 18 (Soyuz 8) October 1969 Soyuz 6 – 179.2 km (111 miles) northwest, Soyuz 7 – 153.6 km (95 miles) northwest and Soyuz 8 – 144 km (89 miles) north of Karaganda R7 (11A511) for all three launches; spacecraft serial numbers (7K-0K) #14 (Soyuz 4); #15 (Soyuz 5);

#16 (Soyuz 8)

4 days 22hrs 42 min 47 sec (Soyuz 6); 4 days 22hrs 40 min 23 sec (Soyuz 7); 4 days 22hrs 50 min 49 sec (Soyuz 8) Soyuz 6 – Antey (Antaeus); Soyuz 7 – Buran (Snowstorm); Soyuz 8 – Granit (Granite)

Soyuz “troika” group flight; rendezvous and docking between Soyuz 7 and 8; space welding experiments on Soyuz 6

Flight Crew

SHONIN, Georgy Stepanovich, 34, Soviet Air Force, commander Soyuz 6 KUBASOV, Valery Nikoleyevich, 34, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 6 FILIPCHENKO, Anatoly Vasilyevich, 41, Soviet Air Force, commander, Soyuz 7

VOLKOV, Vladislav Nikoleyevich, 33, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 7 GORBATKO, Viktor Vasilyevich, 34, Soviet Air Force, research engineer, Soyuz 7

SHATALOV, Vladimir Aleksandrovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander Soyuz 8 and group commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz 4 (1969)

YELISEYEV, Aleksey Stanislovich, 35, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 8, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz 5 (1969)

Flight Log

Soyuz 6 was to have been a solo mission but was flown together with Soyuz 7 and 8 which were to perform a Soyuz 4/5-type rendezvous, docking and transfer mission. Soyuz 6 – without a docking probe – set off first at 16: 10 hrs local time on 11 October. It carried two cosmonauts, Shonin and Kubasov, and entered a 51.7° inclination

|

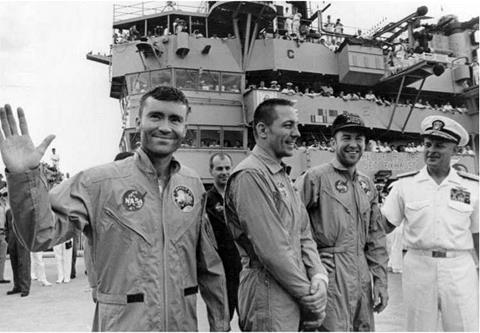

The Soyuz 6 crew of Kubasov (left) and Shonin

|

orbit, which would, after four manoeuvres, reach a maximum altitude of 242 km (150 miles). Their objectives were the usual Soviet ones of “testing, checking, perfecting and conducting” plus a unique experiment called Vulcan, in which automatic welding would be attempted inside the unpressurised Orbital Module. On the 77th orbit of Soyuz 6, three processes were attempted: electron beam, fusible electrode and compressed arc welding, under the control of Kubasov. The samples were returned to Earth. In 1990, some 21 years later, it was revealed that the low-pressure compressed arc had inadvertently almost burned a hole right through the inner compartment flooring and damaged the hull of the Orbital Module. The crew were at first unaware of this as they were sealed in the DM during the welding operation, but found the damage when they entered the OM towards the end of their mission.

When Soyuz 7 was launched at 15: 45 hrs local time from Baikonur the day after, most observers felt that a docking was likely since, at the time, it was not known that

|

The crews of Soyuz 6-8 pose for a “group shot”. Back row from left: Gorbatko, Filipchenko and Volkov (Soyuz 7). Front row from left: Kubasov and Shonin (Soyuz 6), Shatalov and Yeliseyev (Soyuz 8)

|

Soyuz 6 could not do so. Indeed, one of Soyuz 7’s stated objectives was “manoeuvring and navigation tests” with Soyuz 6. But Filipchenko, Gorbatko and Volkov were supposed to dock not with Soyuz 6 but with Soyuz 8, which was duly launched at 15: 19 hrs local time on 13 October, with Shatalov and Yeliseyev, the first Soviet space – experienced crew.

Problems with the Igla rendezvous system were experienced, and a manual attempt at docking was not successful. The nearest the two craft came to one another was 487m (1,600ft), observed for 4 hours 24 minutes by Soyuz 6 from about 1.6km (1 mile) away. Maximum altitudes achieved by Soyuz 7 and 8 were 244 and 235 km (152 and 146 miles) respectively during their missions which, with Soyuz 6, entailed detailed Earth and celestial observations under the group command of Shatalov.

The “mystery missions”, which in total involved 31 orbital change manoeuvres, ended on 17, 18 and 19 October, 179.2km (111 miles) northwest, 153.6km (95 miles) northwest and 144 km (89 miles) north of Karaganda respectively.

Milestones

34th, 35th and 36th manned space flights 13th, 14th and 15th Soviet manned space flights 1st three-manned-spacecraft mission 1st time with seven people in space at once

Shortest turnaround between missions – ten months, for Shatalov and Yeliseyev

Flight Crew

CONRAD, Charles “Pete” Jr., 39, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Gemini 5 (1965); Gemini 11 (1966)

GORDON, Richard Francis Jr., 40, USN, command module pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: Gemini 11 (1966)

BEAN, Alan LaVern, 37, USN, lunar module pilot

Flight Log

Flying to the Moon a second time wasn’t any easier, but it seemed that way after the euphoria of Apollo 11. Indeed, Apollo 12 had two particular hazards, one deliberate and one unpredictable but none the less avoidable. The deliberate hazard was to be the hybrid trajectory to the Moon, which did not guarantee Apollo 12 a “free return’’ by lunar loop if there was a major systems failure en route. The second hazard could have been avoided had NASA not decided to launch the mighty Saturn V in heavy rain and dark storm clouds, seemingly to please the space budget-cutter, President Richard Nixon, who had come to the KSC to watch.

About 36 seconds after 11: 22 hrs local time, with the Saturn already out of view, Pad 39A was hit by lightning. So was Apollo 12. Commander Conrad saw the multicoloured control panel displaying systems shorts and said that it seemed that “everything in the world had dropped out.’’ LMP Bean restored systems as the second and third stages proceeded effortlessly into 199 km (124 miles) 32° orbit. All the electrical circuits were checked and the go for the Moon was given. The S-IVB burned for 5 minutes 45 seconds and the transposition and docking manoeuvre was successful, but the S-IVB was placed into an unusual and highly elliptical orbit of the Earth, rather than into solar orbit, due to a malfunction.

The TV shows were jocular and informative. Conrad and Bean checked out the Lunar Module, and one mid-course correction was made to place Apollo out of the free return and on course for a lunar orbit with desirable lighting conditions at the landing point. Apollo 12’s SPS lit up on the lunar far side and placed the spacecraft

|

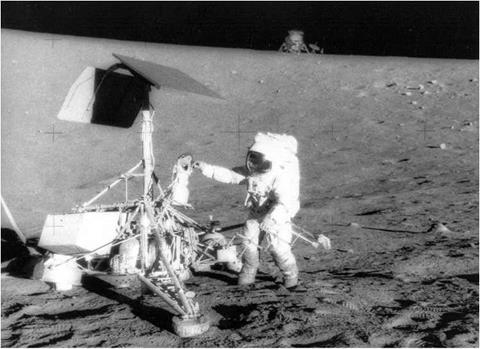

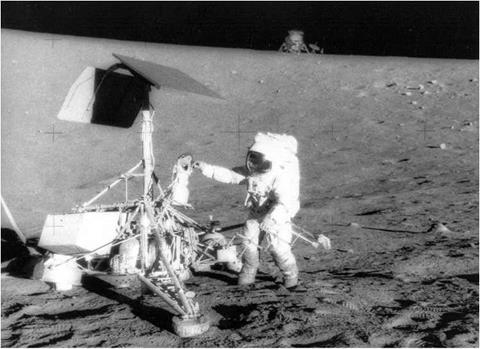

Pete Conrad examines the Surveyor 3 spacecraft. The Apollo 12 Lunar Module can be seen on the horizon.

|

into a 110 by 312 km (68 x 194 miles) orbit, which was adjusted two orbits later to an eventual 110 km (68 miles). At T + 107 hours 54 minutes, the Lunar Module became Intrepid and the Command Module Yankee Clipper, illustrating that this was an allNavy crew. DOI began at T + 109 hours 23 minutes with a 29-second firing placing Intrepid at a perilune of 14.4 km (9 miles) for the PDI. Before this, there was hectic activity between the ground and the crew to update the LM’s navigation programme, which continued two minutes into the burn that began at T + 110 hours 20 minutes.

The high-spirited crew came into their Ocean of Storms landing site, close to the unmanned Surveyor 3 spacecraft which had landed there in 1967. Conrad landed Intrepid about 856 m (2,808 ft) northwest of Surveyor at T + 110 hours 32 minutes at 3°11’51" south 23°23’7.5" west. CMP Gordon spotted both Intrepid and Surveyor from orbit in Yankee Clipper. The first moonwalk began at T + 115 hours 10 minutes when the jocular Conrad hopped, skipped and hummed across the surface. After joining him, Bean took the colour television camera to place it on a tripod, but the camera was pointed at the Sun and blacked out. The by now dwindling TV audiences switched off.

The first 3 hour 56 minute EVA on 19 November involved erecting the US flag and deploying the first ALSEP array of lunar experiments, one of which was powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator with a radioactive fuel source. The second

EVA on 20 November, lasting 3 hours 49 minutes, was highlighted by the visit to Surveyor, bits of which were cut off to be taken home for analysis. Conrad’s fall in the lunar dust caused a “spacesuit might leak’’ scare, but from the antics of later moon – walkers, one wonders what the fuss was about.

The highly successful moonwalks over, after 31 hours 31 minutes on the Moon, Intrepid sailed for Yankee Clipper. The rendezvous and docking 3 hours 30 minutes later was watched live by TV audiences, who could even see Intrepid’s crew in the windows of the LM and the little spurts of the RCS jets. Conrad and Bean removed their dusty spacesuits and crossed into Yankee Clipper naked, except for their headsets. Intrepid was sent crashing into the Moon and the reverberations from the impact were picked up by the ALSEP seismometer now on the surface.

Yankee Clipper broke anchor after 45 orbits and 88 hours 56 minutes over the Moon. The crew witnessed a spectacular solar eclipse on the way home and splashed down near USS Hornet at 15° south 165° west at T + 10 days 4 hours 36 minutes 25 seconds. Like the Apollo 11 crew, Conrad, Gordon and Bean had to live in the Apollo quarantine container for three weeks to ensure that no “moon bugs’’ came home with them.

Milestones

37th manned space flight

22nd US manned space flight

6th manned Apollo flight

6th Apollo CSM manned flight

4th Apollo LM manned flight

4th manned flight to and orbit of the Moon

2nd manned lunar landing and moonwalk

1st manned mission with two EVAs

1st manned spacecraft to spend a day on the Moon

1st manned mission to use radioisotope thermoelectric generators

8th US and 10th flight with EVA operations

Flight Crew

LOVELL, James Arthur Jr., 42, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: Gemini 7 (1965); Gemini 12 (1966); Apollo 8 (1968) SWIGERT, John Leonard “Jack” Jr., 39, command module pilot HAISE, Fred Wallace Jr., 36, lunar module pilot

Flight Log

Command module pilot Thomas “Ken” Mattingly had the bad luck, two days before the flight of Apollo 13, to be declared not immune to the German measles that he had been exposed to by back-up LMP Charlie Duke. He was dropped and replaced by back-up Jack Swigert, who was put through his paces in the simulator to ensure his readiness and compatibility with the remaining prime crew members, James Lovell and Fred Haise. Lift-off seemed routine at 14: 32hrs local time, but the Saturn V burn lasted 44 seconds longer, because the four remaining engines of the S-II had to burn for an extra 34 seconds to make up for the loss of the fifth one, and the S-IVB had to burn for an additional ten seconds.

Initial orbit of 33.5° and 156 km (97 miles) apogee was achieved. The S-IVB ignited, the transposition and docking was successful and the stage was sent towards an impact on the Moon, big enough to be detected by the Apollo 12 seismometer. The television pictures were of high quality, but were not shown live by any network. Apollo 13 indeed seemed a milk run to the Moon, targeted for the Fra Mauro highlands. Then, at T + 55 hours 55 minutes 20 seconds on 13 April, oxygen tank No. 2 in the Service Module, which had undetected heater switches welded together due to an electrical malfunction in a pre-launch test, exploded 328,000 km (222,461 miles) from Earth.

The reaction of the crew was calm and stoic as they faced a lingering death in space. Power was going down fast in the Command Module. The only hope was to use the LM Aquarius, thankfully still attached, as it was the trans-lunar coast rather than

|

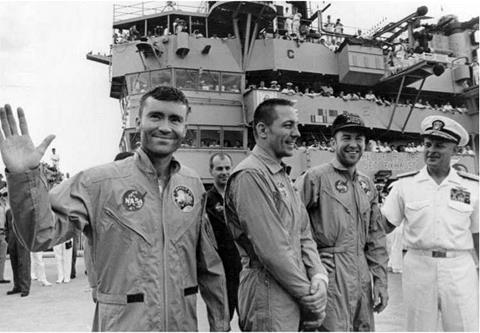

Apollo 13 crew (1 to r) Haise, Swigert and Lovell, relieved to be back on Earth after a trying mission

|

the return journey. Aquarius’s descent engine was used three times, T + 61 hours 30 minutes, for 30 seconds, to get Apollo 13 back on a lunar looping “free return’’ trajectory which would at least guarantee making landfall on Earth – somewhere, hopefully in the Indian Ocean: for 4 minutes 28 seconds to speed the return journey, at T + 142 hours 53 minutes; and for 15.4 seconds to fine-tune the trajectory. Rookies Haise and Swigert had strained at their windows to get a peek at the lunar far side during the lunar loop, which made them and Lovell the farthest travellers from Earth, at a distance of 397,848 km (247,223 miles).

Conditions on board were pitiful. It was extremely cold and the spacecraft was operating on the power equivalent of a single light bulb by the end of the mission. The crew, ably supported by thousands of engineers, scientists and fellow astronauts on the ground, even had to jury-rig an air conditioning unit to get rid of carbon dioxide. Aquarius was separated just before re-entry, followed by the Service Module, giving the incredulous crew their first view of the devastation that had been below them. Left with a little battery power, the Command Module Odyssey limped home to a splashdown at T + 5 days 22 hours 54 minutes 41 seconds, close to the USS Iwo Jima at 21° south 165°west. The shortest US three-person flight in history had captured the hearts of the world, and ended with a service of thanksgiving on the recovery ship.

The events of Apollo 13, as well as a tightening of the NASA budget, helped to seal the fate of future missions. Apollo 20 had already been axed in January 1970, and

by September, Apollo 15 and 19 had been cancelled and the remaining missions renumbered to end with Apollo 17. The fear of losing a crew in space, or of their being stranded on the Moon with no hope of rescue, and the desire to move on to new programmes closer to Earth, together with the escalating cost of the war in southeast Asia and social unrest in the United States, all contributed to the end of the Apollo lunar programme.

Milestones

38th manned space flight

23rd US manned space flight

7th Apollo manned space flight

7th Apollo CSM manned flight

5th Apollo LM manned flight (docked only)

5th manned flight to the Moon

1st manned lunar loop flight

1st aborted lunar landing mission

1st flight by crewman on fourth mission

1st flight by crewman on second Moon mission

|

Int. Designation

|

1984-034A

|

|

Launched

|

6 April 1984

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

13 April 1984

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-099 Challenger/ET-10/SRB BI-012/SSME #1 2109; #2 2020; #3 2012

|

|

Duration

|

6 days 23 hrs 40 min 7 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Challenger

|

|

Objective

|

Repair and re-deployment of Solar Max; deployment of Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF)

|

Flight Crew

CRIPPEN, Robert Laurel, 46, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-1 (1981); STS-7 (1983)

SCOBEE, Francis Richard “Dick”, 44, USAF, pilot

HART, Terry Jonathan, 37, civilian, mission specialist 1

NELSON, George Driver, 33, civilian, mission specialist 2

VAN HOFTEN, James Douglas Adrianus, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

Space Shuttle flights were seemingly becoming more and more audacious mission by mission. STS 41-C was to retrieve, repair and redeploy the Solar Maximum Mission, or Solar Max, a science satellite that had been launched in 1980 but had blown some fuses, spoiling its fine pointing ability and rendering it useless. It was a tough assignment for the Challenger crew, led by the inspiring Bob “Mr. Shuttle” Crippen. Challenger took off two days late from the Kennedy Space Center at 08:58 hrs local time. For the first time, the Shuttle made a direct insertion into 28.45° orbit, to conserve valuable OMS propellant for the intensive manoeuvres required for Solar Max rendezvous. Lower than anticipated SRB performance almost resulted in the use of the OMS engines to achieve the planned orbit, which would have cancelled the Solar Max portion of the flight. The crew reached a maximum altitude of 435 km (270 miles) during the mission.

Before Solar Max could be retrieved, Challenger’s payload bay had to be emptied of a rather unique cylindrical satellite which almost filled it completely. This was the Long Duration Exposure Facility, or LDEF, which was a 12-sided craft with 57 materials experiments mounted on the outside. LDEF was scheduled to be retrieved in 1985 to enable scientists to assess the effects of exposure to the space environment on

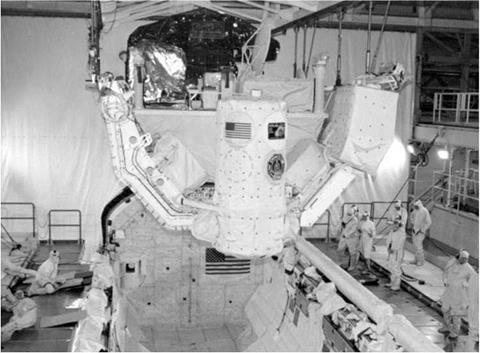

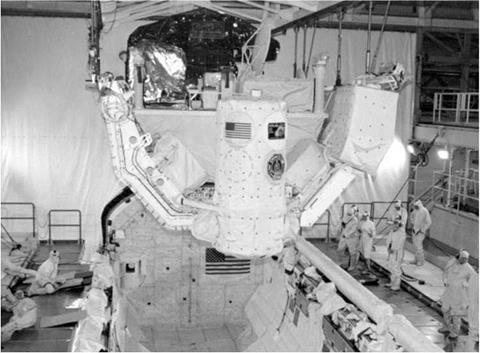

|

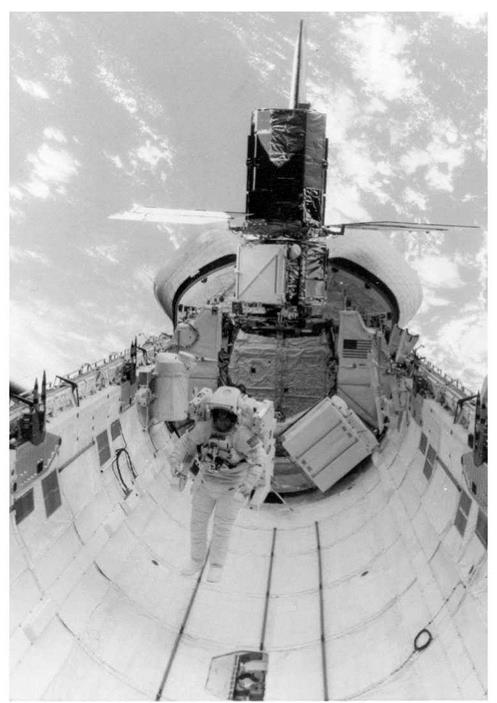

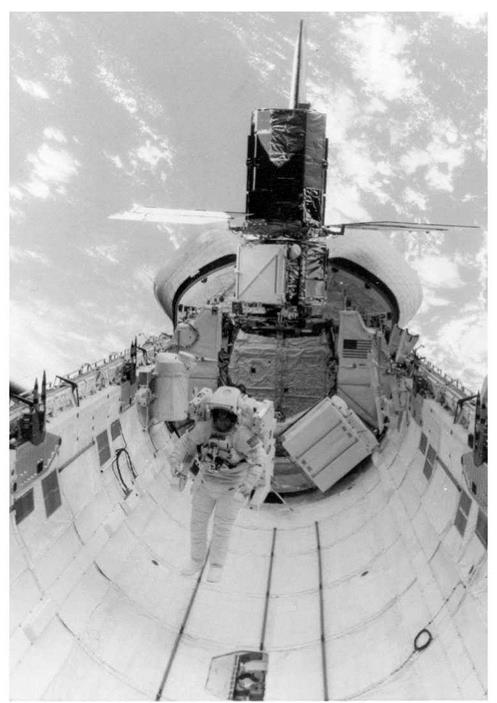

‘Ox” Van Hoften test-flies an MMU in the payload bay of Challenger during STS 41-C

|

the different materials. Its deployment over the Kennedy Space Center, using the RMS, was a spectacular sight.

Crippen, his pilot Dick Scobee, and Challenger’s rendezvous radar, star trackers and computers, got to work on the Solar Max rendezvous, which was achieved effortlessly on 8 April. The rotating spacecraft was about 54 m (177 ft) away as mission specialist George Nelson (EV1), wearing an MMU, flew from Challenger. Attached to his chest was a T-pad docking device with which he was to attach himself to Solar Max, to steady it for an RMS grapple. But try as he may, while a soft-docking was achieved, Nelson could not make a hard dock with the satellite. In an effort to steady it manually, Nelson undocked and tried to hold the solar panels. Solar Max went even more out of control and the mission seemed doomed. The unhappy Nelson was recalled to Challenger.

Its solar panels now pointing away from the Sun, Solar Max was losing power, but ground engineers managed to bring it under some sort of control, so that Challenger, its mission extended one day, could attempt a direct RMS grab. Mission specialist Terry Hart’s one and only chance had to succeed and his deft handling worked. Solar Max was captured. During a record 7 hour 16 minute EVA on 11 April, Nelson and James van Hoften, who had assisted during the first 2 hour 57 minute EVA, repaired Solar Max, which was later redeployed to continue its mission. The repair to the satellite’s electronics and attitude control system was a great demonstration of what a crew and the Shuttle could do. Van Hoften (EV2) was allowed a little go on the MMU, clocking up 28 minutes on Unit 3, compared with Nelson’s 42 minutes on Unit 2. It was during the STS 41-C EVAs that Nelson experienced a spacewalker’s worst nightmare (apart from a punctured pressure suit) – a minor urine contamination problem – in other words his waste collection device leaked. Fortunately, the liquid coolant garment (LCG) soaked up some of the liquid like a sponge, and though some helmet fogging was experienced, post-flight inspection revealed that no urine had entered the helmet. The fogging was a result of turning down the LCG after the astronaut felt cold as the urine was soaked up. The real danger of inhaling a small globule of any liquid in an EVA suit is that it could become trapped in the throat. The possibility of an astronaut being drowned by less than a teaspoon of liquid is a very real one. When Nelson returned to the airlock and crew compartment, the aroma of six hours perspiration in the suit coupled with the soaking urine reminded his crew members of “the inside of a toilet that had not been cleaned.’’ The smell was so bad that Nelson’s colleagues threatened to put him back outside for the remainder of the mission!

The icing on the cake was to be a landing back at the Kennedy Space Center but, as was the case with Crippen’s STS-7 mission, bad weather thwarted the attempt. Challenger came home after a one-orbit extension, on runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base at T + 6 days 23 hours 40 minutes 7 seconds. “Mr. Shuttle’’ headed straight for the simulators for his next mission. Solar Max re-entered in 1990.

Milestones

98th manned space flight 42nd US manned space flight 11th Shuttle mission 5th flight of Challenger

1st satellite retrieval, in-orbit repair and redeployment

1st astronaut docking with satellite

19th US and 26th flight with EVA operations

Flight Crew

DZHANIBEKOV, Vladimir Aleksandrovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 4th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz 27 (1978); Soyuz 39 (1981); Soyuz T6 (1982) SAVITSKAYA, Svetlana Yevgenyevna, 35, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz T7 (1982)

VOLK, Igor Petrovich, 47, civilian, research engineer

Flight Log

Lift-off of this Soyuz with a difference came at 23: 41 hrs local time at Baikonur. The commander was making his fourth flight, the flight engineer was the first woman to make two missions and the cosmonaut researcher was a Buran space shuttle pilot on a familiarisation trip. To cap it all, the commander and flight engineer made an EVA on the mission, the first by a female and the first by a man and a woman together. All these statistical firsts seemed to be linked to the fact that in three months’ time the US was to launch a Shuttle to perform all these facts and feats.

Soyuz T12 was not altogether a Khrushchev-style propaganda mission, since Vladimir Dzhanibekov, the commander, was giving Salyut 7 a once-over and training the resident crew in the updated repair techniques necessary to keep it operational and which had been developed since their launch. Docking with Salyut occurred on 18 July and seven days later, Dzhanibekov and Svetlana Savitskaya started a 3 hour 55 minute EVA, during which both operated welding equipment. A 30 kg (66 lb) portable electron beam welder was carried outside, together with the control panel, transformer and metal samples. Savitskaya started the cutting, soldering and welding tests and was followed by her commander.

At the end of the spacewalk, the cosmonauts retrieved some samples from the outside of Salyut. The rest of the mission included experiments with the French Cytos 3 biological unit. The visiting mission was a long one compared with those that went

|

On board Salyut 7, clockwise from bottom left: Dzhanibekov, Savitskaya, Solovyov, Yolk, Atkov and Kizim

|

|

before and ended at T + 11 days 19 hours 14 minutes 36 seconds. Maximum altitude during the 51.6° mission was 372 km (231 miles).

As Buran was still a state secret, the activities of Volk were quite vague. Volk had trained for a flight to Salyut 7 with Kizim and Solovyov but his mission had been delayed due to the problems Salyut was experiencing. After completing the T12 mission and shortly after landing, Volk piloted both the Tupolev 154 and MiG 25 with adapted Buran control systems in order to test the effects of a 12-day space flight on his piloting skills. This was a simulation of what a Buran pilot would have to experience upon returning the shuttle from orbit, something the Americans had been doing for the previous three years.

Milestones

99th manned space flight

57th Soviet manned space flight

50th Soyuz manned space flight

11th Soyuz T manned space flight

1st space flight by female on second mission

1st EVA by female

1st male-female EVA

9th Soviet and 27th flight with EVA operations Final manned space flight from Pad 31, Site 6

First manned flight of new Soyuz uprated booster (11A511U2) – Soyuz U2

|

Int. Designation

|

1988-106A

|

|

Launched

|

2 December 1988

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed 6

|

December 1988

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-23/SRB BI-030/SSME #1 2027;

|

|

#2 2030; #3 2029

|

|

Duration

|

4 days 9 hrs 5 min 35 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Atlantis

|

|

Objective

|

3rd classified DoD Shuttle mission

|

Flight Crew

GIBSON, Robert Lee “Hoot”, 42, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 41-B (1984); STS 61-C (1986)

GARDNER, Guy Spence, 40, USAF, pilot

MULLANE, Richard Michael, 43, USAF, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-D (1984)

ROSS, Jerry Lynn, 40, USAF, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 61-B (1985)

SHEPHERD, William McMichael, 39, USN, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

STS 62-A, the first manned polar orbiting space flight, was to have been launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California in 1986. The flight was cancelled and the Vandenberg pad mothballed after the Challenger disaster. It re-emerged as STS-27, with a new commander, Hoot Gibson, replacing Bob Crippen, and a new mission specialist, William Shepherd, replacing Dale Gardner. Orbiter Atlantis was equipped with an enormous electronic intelligence and digital imaging reconnaissance satellite which was to be placed into a 57° inclination orbit, the highest inclination permitted by a Shuttle from the KSC.

The first launch attempt was called off on 1 December with the crew aboard at T — 9 minutes due to high winds at altitude. There was a minor delay the following day, before the spectacular take-off at 09: 30 hrs local time, with the Shuttle making a dramatic, sloping lateral movement away from the pad as it performed a 140° roll programme and headed up the east coast of the USA. Debris from the top of one of the SRBs broke away and severely damaged some of the underside of Atlantis, as the crew would see after they landed. Once in orbit the official communications, which began at T — 9 minutes, ended for this military mission.

|

L to r: Gardner, Gibson and Shepard at work during STS-27

|

According to analysis and ground observations, the giant Lacrosse was deployed from the payload bay by the RMS and inspected. Its 45 m (147 ft) span solar panels were supposed to unfurl but did not at first. If an EVA was required to free the panels it was not announced but the panels were freed, possibly by an RMS-induced shake, and the deployment followed at about T + 7 hours into the mission. Little information about it was released, except that a gallon of water had leaked in the cockpit. STS-27 marked the third time that eleven people were in space at once, with six cosmonauts on board the Mir space station at the same time.

The flight ended at T + 4 days 9 hours 5 minutes 35 seconds on runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base after a northerly approach from its high-inclination orbit, only the second afternoon landing in the Shuttle programme. The crew busied themselves examining the underside of the orbiter, which had suffered extensive damage to its heatshield tiles, resulting in the need to replace 707 of them, the greatest tile loss on the programme. Despite this, STS-27 had qualified Atlantis for the Return – to-Flight programme.

Milestones

123rd manned space flight 57th US manned space flight 27th Shuttle mission 3rd flight of Atlantis

|

Int. Designation

|

1991-054A

|

|

Launched

|

2 August 1991

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

11 August 1991

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-47/SRB BI-045/SSME #1 2024; #2 2012; #3 2028

|

|

Duration

|

8 days 21 hrs 21 min 25 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Atlantis

|

|

Objective

|

Deployment of the fifth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-E) by IUS-15 upper stage

|

Flight Crew

BLAHA, John Elmer, 43, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-29 (1989), STS-33 (1989)

BAKER, Michael Allen, 37, USN, pilot

LUCID, Shannon Wells, 48, civilian, mission specialist 1, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-G (1985), STS-34 (1989)

LOW, George David, 35, civilian, mission specialist 2 ADAMSON, James Craig, 45, US Army, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

The primary objective of STS-43 was achieved barely twelve hours into the mission, when the fifth TDRS satellite was deployed and then placed in its operational circular orbit after two burns of the IUS. Following the mission, the crew returned to Earth with data and results from four payload bay experiments, eight mid-deck payloads, thirteen Detailed Test Objectives (DTO) and nine Detailed Supplementary Objectives (DSO), most of which were linked to extended-duration missions in orbit.

The deployment of a TDRS satellite from a Shuttle rarely attracted headline news and these became some of the “quieter” missions in the programme. However, the work conducted by the crew after the deployment contributed to the development of techniques and procedures that would be significant for missions carried out years later on Mir and ISS. The launch was originally set for 23 July, but was delayed by a day to replace a faulty integrated electronics assembly (which controlled the separation of the ET from the orbiter). Five hours before the second launch attempt, the mission was postponed again due to a faulty main engine controller on SSME #3. The launch was reset for 1 August, but was again delayed, this time due to cabin pressure

|

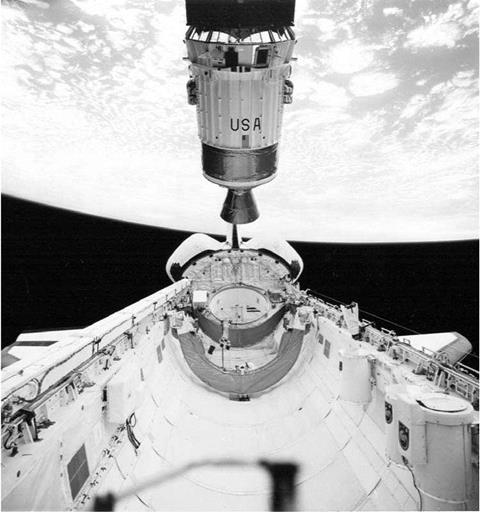

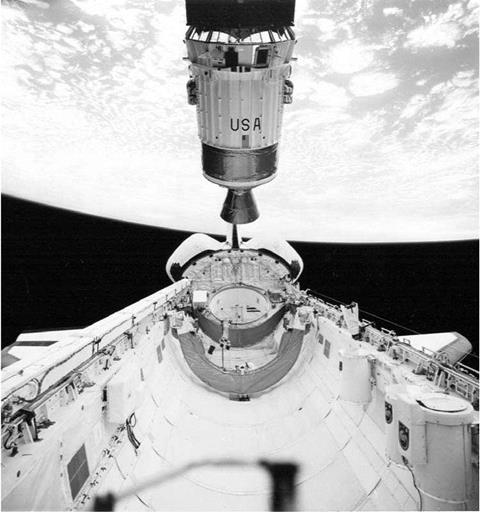

TDRS-E leaves the payload bay of Atlantis atop IUS-15 just six hours after launch from KSC. When it reached its operational station it was renamed TDRS-5, replacing TDRS-3 at 174° west longitude. The GAS canisters are seen to the right of frame along the side of the payload bay wall

|

vent valve problems. It was postponed a further 24 hours due to infringements of Return-To-Launch-Site (RTLS) weather parameters.

When the mission did finally launch, the crew observed and photographed auroras and lightning discharges, along with four hurricanes in the Pacific Ocean. Measurements of solar UV radiation and UV backscatter radiation from Earth’s clouds were also obtained, which would be used to corroborate readings from instruments aboard NIMBUS 7 and the NOAA 9 and 11 satellites, which measured ozone concentration in the upper atmosphere. The In-Flame Preparation in Microgravity experiment was part of an improved fire safety technology investigation connected with safety in future manned spacecraft, while studies of the operation of two large heat pipe radiation elements were linked to the space station. The crew also worked with protein crystallisation, polymer membrane processing and biomedical and fluid science experiments. They also evaluated new Shuttle computers, associated software and improved cursor control devices. In the medical experiments, data was obtained from use of the Lower Body Negative Pressure Device, as well as monitoring cardiovascular performance of the crew in anticipation of future investigations during long space flights. Blaha and Lucid would both participate in their own long-duration flights aboard space station Mir in 1996 and 1997.

Milestones

143rd manned space flight

72nd US manned space flight

42nd Space Shuttle mission

9th mission for Atlantis

5th TDRS Shuttle deployment mission

1st female astronaut to make three space flights (Lucid)

1st planned landing at KSC since January 1986

|

Int. Designation

|

1993-023A

|

|

Launched

|

7 April 1993

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

17 April 1993

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 33, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-103 Discovery/ET-54/SRB BI-058/SSME #1 2024; #2 2033; #3 2018

|

|

Duration

|

9 days 6 hrs 8 min 24 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Endeavour

|

|

Objective

|

Operation of ATLAS-2 science package located in the payload bay; SPARTAN-201 free flying astronomy platform

|

Flight Crew

CAMERON, Kenneth Donald, 43, USMC, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-37 (1991)

OSWALD, Stephen Scott, 41, USNR, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-42 (1992)

FOALE, Colin Michael, 36, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-45 (1992)

COCKRELL, Kenneth Dale, 42, USNR, mission specialist 2 OCHOA, Ellen Lauri, 34, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

The 6 April launch attempt for STS-56 was halted at T — 11 seconds by the orbiter’s computers. Incorrectly configured instrumentation on the LH high-point bleed valve in the main propulsion system indicated it was in an “off” position instead of the “on” position. The launch was set for 8 April, after a 48-hour scrub was implemented.

Once again the crew worked in two shifts throughout the mission. Foale and Cockrell operated the Red Shift, while Cameron, Oswald and Ochoa worked the Blue Shift. All seven ATLAS instruments had flown on ATLAS-1 in 1992 and were scheduled to fly a third time on ATLAS 3 in 1994. The ATLAS payload continued the collection of data regarding the relationship between energy from the Sun and the middle atmosphere of Earth, and how such a relationship affects the ozone layer. The other primary payload was deployed by the RMS on 11 April. The Shuttle Pointing Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy-201 (SPARTAN-201) was a free-flying science platform whose configuration was designed to study the velocity and acceleration of solar wind particles and to make observations of the Sun’s

|

Mounted on a Spacelab pallet at centre is the primary payload of STS-56, ATLAS-2. The SPARTAN-201, with a protective covering over its instruments, is mounted directly behind ATLAS-2. This photo was taken in Bay 3 of the Orbiter Processing Facility at KSC during cargo-processing in February 1993

|

corona. The data collected during its independent flight was stored onboard tape recorders for play-back after its return to Earth. The RMS retrieved the SPARTAN – 201 on 13 April.

In addition to the primary payload, the flight included a suite of mid-deck payloads, focusing on biomedical and life science research, Earth location targeting equipment and optical calibration tests. In addition, SAREX was flown again, with the crew making numerous radio contracts with schools across the globe. They also reported brief contact with the Russian Mir space station, the first such confirmed contact between the Shuttle and space station using amateur equipment.

The landing of STS-56 was originally planned for 16 April, but was delayed due to bad weather conditions. The payload commander on this mission, Mike Foale, indicated that he did not wish to fly the third ATLAS mission having flown the first two, as he did not wish to become known as “Mr. Atlas” for the rest of his astronaut career. He suggested Ellen Ochoa as the next PC. This format of re-flying crew members on the same series of missions freed up training time and utilised actual flight experience to provide an on-going flow of CB contact with series payloads from one flight to the next.

Milestones

159th manned space flight

84th US manned space flight

54th Shuttle mission

16th flight of Discovery

4th Spacelab pallet-only mission

1st amateur radio contact between Shuttle and Mir

Cockrell celebrates his 43rd birthday in space (9 Apr)

Flight Crew

DEZHUROV, Vladimir Nikolayevich, 32, Russian Air Force, commander STREKALOV, Gennady Mikhailovich, 54, civilian, flight engineer, 5th mission Previous missions: Soyuz T3 (1980); Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10-1 pad abort (1983); Soyuz T11 (1984); Soyuz TM10 (1990)

THAGARD, Norman Earl, 51, civilian, NASA cosmonaut researcher,

5th mission

Previous missions: STS-7 (1983); STS 51-B (1985); STS-30 (1989); STS-42 (1992)

Flight Log

Veteran Shuttle astronaut Norman Thagard became the first American to fly into space on a foreign launch vehicle and spacecraft as crew member of Soyuz TM21. He was also a member of the 18th resident crew on Mir and would participate in a programme of 28 experiments, most of which were focused on biomedical research. When the joint programme was planned, it was expected that most of the American research equipment would be delivered with the Spektr research module, but this was seriously delayed (and in fact did not dock with Mir until half-way through Thagard’s residence), so most of Thagard’s equipment had to be delivered by Progress re-supply craft. Scheduling problems affected the planning of this mission due to delays in preparing Spektr for launch, which in turn affected the scheduling of STS-71, the first Shuttle-Mir docking mission. Most of the working time of the two Russian cosmonauts was consumed by maintenance and repair tasks, mostly on the environmental and thermal regulation systems of the station. Reports indicated that at least 40 per cent of their working time was taken up with such tasks, as the station was now beginning to show signs of its age.

In preparation for receiving the new module at the station, Progress M23 was undocked from the front port of Mir. Then the two Russian cosmonauts had to complete a series of EVAs to retract the solar arrays on Kristall and reposition them on Kvant to facilitate the rearrangement of the module using the Ljappa arm. The first

|

US astronaut Norm Thagard in his sleep restraint aboard Mir, the first of seven NASA astronauts to live and work aboard the Russian station as resident crew members

|

three EVAs were in support of retracting the solar arrays on Kristall. This module had been located initially where Spektr was due to be docked at the —Y port (negative Y – these locations refer to the facing of the docking ports on the station along the X, Y and Z axes) so it had to be moved. Kristall was moved on 26 May from the — Y port to the —X port, and then to the —Z port on 29 May after the cosmonauts had performed an internal EVA (IVA) to relocate the docking systems. Spektr docked at the —X port on 1 June and the next day was moved to the —Y port, again after an IVA to relocate docking equipment. Kristall was rotated to the —X port on 10 June and Atlantis docked with it on 29 June during the STS-71 mission. After the departure of the Shuttle, Kristall was relocated from the —X port back to the —Z port on 17 July.

The five EVAs, totalling 18 hours 43 minutes were conducted on 12 May (6 hours 14 minutes), 17 May (6 hours 42 minutes), 22 May (5 hours 14 minutes), 29 May (21 minutes IVA) and 2 June (22 minutes IVA). On 5 June, the two arrays of Spektr were deployed but one of them failed to fully open and an unscheduled EVA was planned for 16 June to manually unfurl the array in order to provide sufficient power during the docked phase of the Atlantis STS-71 mission. However, Strekalov argued that the EVA was unnecessary and very hazardous as they had not trained for it.

He refused to conduct the EVA despite pressure from Dezhurov. The electrical power was eventually estimated to be sufficient for the docking, but the cosmonauts were fined 15 per cent of their fee for the mission for failing to conduct their sixth EVA.

Thagard had to contend with several frustrating problems during his stay on the station. A freezer broke down, causing many of the samples he had taken to be lost. He also felt isolated, as communication with Earth was far less frequent on Mir than on the Shuttle, but kept himself informed of what was happening on Earth thanks to contact with a ham radio operator in California. Thagard also lost weight and became bored, although the arrival of the Spektr module helped keep him busy. It quickly became apparent to the Americans that flying with the Russians on a long-duration Mir mission would be very different to flying short missions on the Shuttle. Thagard’s flight became the longest by an American astronaut to date, finally surpassing the 84-day record held by the Skylab 4 crew since 1974. Just like the pioneering Skylab long-duration missions, Thagard’s 115 days in space proved to be another valuable, if difficult, learning curve for NASA. It was also clear, however, that there would be many more hurdles to overcome during the Phase 1 programme.

Milestones

178th manned space flight

80th Russian manned space flight

18th Mir resident crew

73rd manned Soyuz mission

20th manned Soyuz TM mission

26th Russian and 57th flight with EVA operations

1st US astronaut launched on Russian spacecraft

1st US astronaut crew member on a main Russian crew

1st US resident astronaut on Mir

Thagard celebrated his 52nd birthday in space (3 Jul)

1997-039A 7 August 1997 1997-039A 7 August 1997

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 19 August 1997

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

OV-103 Discovery/ET-87/SRB BI-089/SSME #1 2041;

#2 2039; #3 2042

11 days 20hrs 26 min 59 sec

Discovery

CRISTA-SPAS-02 operations

Flight Crew

BROWN Jr., Curtis Lee, 41, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-66 (1994); STS-77 (1996)

ROMINGER, Kent Vernon, 41, USN, pilot, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-73 (1995); STS-80 (1996)

DAVIS, Jan, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-60 (1994)

CURBEAM Jr., Robert Lee, 35, USN, mission specialist 2 ROBINSON, Stephen Kern, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3 TRYGGVASON, Bjarni Vladimir, 52, civilian, Canadian payload specialist 1

Flight Log

Continuing the Mission to Planet Earth programme, as well as preparations for the construction of ISS, the STS-85 mission featured a complex payload from Germany, Japan and the US, as well as an international crew.

The primary payload on this flight was the Cryogenic IR Spectrometer and Telescope for the Atmosphere Shuttle Pallet Satellite-2 (CRISTA-SPAS-2), making its second flight on the Shuttle as part of the fourth cooperative mission between the German space agency DARA and NASA. There were three telescopes and four spectrometers on the satellite. Deployed on FD 1, it operated for over 200 hours and was retrieved on FD 10. After completing its primary objective, CRISTA-SPAS was used in a simulation exercise to prepare for the first ISS assembly flight, STS-88, with the payload being manipulated as if it were the Russian Functional Cargo Block (FGB-Zarya) that was to be attached to the US Node 1 (Unity).

The Technology Applications and Science 01 (TAS-01) payload included seven separate experiments to gather data on the topography of the Earth and its atmosphere, to study the energy from the Sun and to evaluate new thermal control devices. International Extreme UV Hitchhiker 02 was a set of four experiments that studied

|

Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason inputs data into a computer for the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM) experiment located on the mid-deck of Discovery. Behind him, the use of mid-deck lockers for stowage both inside and outside is evident

|

UV radiation from stars, the Sun and other solar system sources. The Japanese Manipulator Flight Demonstrator (MFD) consisted of three separate experiments located on a support structure in the payload bay and were designed to test a mechanical arm that was being evaluated for possible inclusion on the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) planned for ISS. Despite some glitches, a series of exercises was performed by the crew in space and a team of operators on the ground.

There was also a range of in-cabin payloads, including a UV imaging system to observe Comet Hale-Bopp, crystal growth and materials-processing experiments, the Orbiter Space Vision System (to be used during ISS assembly for determining precise alignment and pointing capability). Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason, principle investigator of the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM), had a major role on the flight in evaluating his own equipment, performing fluid physics experiments to determine sensitivity to spacecraft vibrations when using MIM, and its application to ISS and future research facilities. The MIM had been in operation aboard Mir since April 1996 and was first operated by Shannon Lucid, where it supported a number of Canadian and US experiments in materials science and fluid physics.

The 18 August landing opportunities were waived off due to ground fog in the local area, allowing the crew an extra day on orbit.

Milestones

201st manned space flight 116th US manned space flight 86th Shuttle mission 23rd flight of Discovery

| |

1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

1997-039A 7 August 1997

1997-039A 7 August 1997