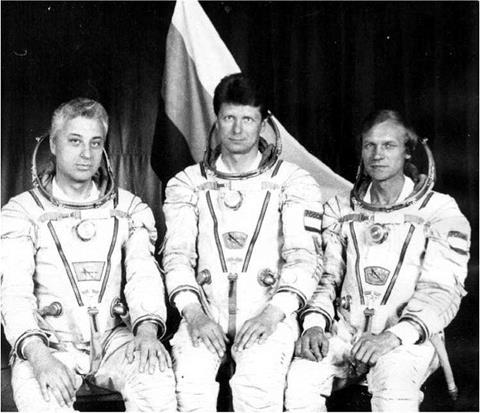

Flight Crew

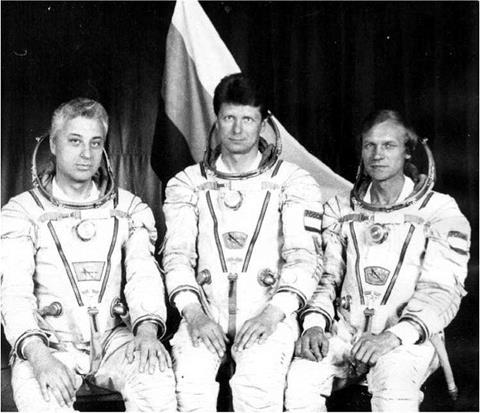

PADALKA, Gennady Ivanovich, 40, Russian Air Force, commander AVDEYEV, Sergei Vasilyevich, 42, civilian, flight engineer, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz TM15 (1992); Soyuz TM22 (1996)

BATURIN, Yuri Mikhailovich, 49, Russian Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

Before becoming a cosmonaut, Yuri Baturin had been a space physicist. He then became the national security advisor for President Boris Yeltsin and then the Defence Council Secretary. He was also an advisor on space matters and was attached to the 1997 Air Force cosmonaut selection (with the rank of colonel). In April 1998, he completed a 12-day mission to Mir, returning with the EO-25 crew. After his mission he stated that, in his opinion, the Mir complex should be kept operating for at least two years beyond the planned 1999 decommission date.

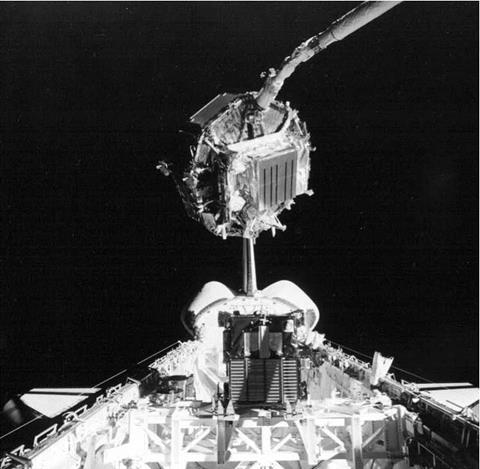

When Baturin and the E0-25 crew departed Mir, the two remaining cosmonauts pursued their EO-26 programme. This included an internal EVA inside the forward node to reset electrical connectors inside the Spektr module. Their subsequent 10 November EVA (5 hours 54 minutes) featured the deployment of Japanese and French experiments. They then continued their programme of experiments, many of which had been left on board the station by international visitors, enhancing the return from the investment in those experiments.

Mir was almost forgotten in the wake of the launch of the first element of ISS – the Zarya module – in November. This was followed by the first Shuttle mission to add other elements – the US node Unity – the following month. With ISS in orbit, Russia indicated that it was looking for private funds to keep Mir aloft into the new

|

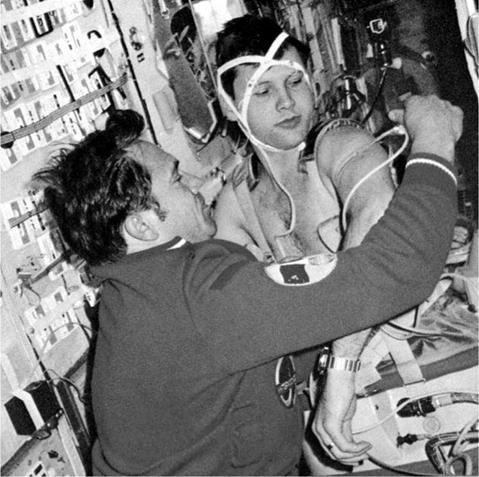

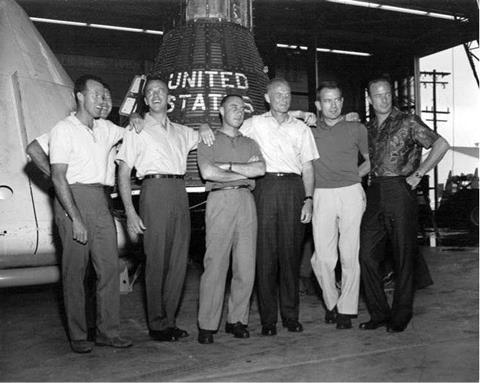

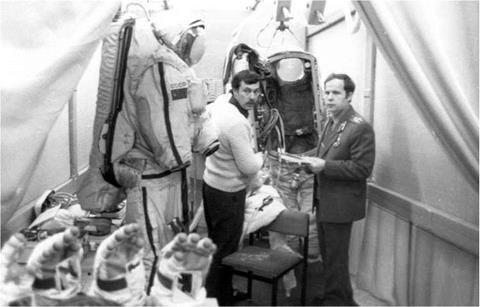

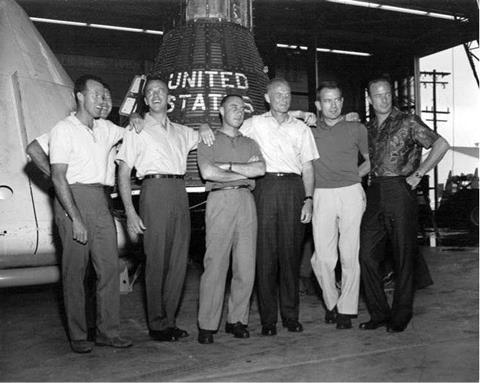

The Soyuz TM28 crew included Baturin (left), a former advisor to President Boris Yeltsin, along with Padalka (centre) and Avdeyev

|

millennium, as governmental support would end in 1999 when its commitment to ISS increased. When news came that the Service Module of the new station (Zvezda) would be delayed into 2000 and with it the capability of supporting a resident crew, the call to maintain Mir operations beyond 1999 intensified. There was also discussion about further commercial ventures for the station, including filming part of a movie aboard Mir with actors making a short visiting mission to film scenes in orbit. With news that a new investor might support further use of Mir, there remained the question of fitting in the two missions already planned as the EO-26 residence drew to a close and Mir funding from the government ended. The two options were to either fly a Russian commander with the French flight engineer to see out the planned programme, or to leave Avdeyev aboard Mir to join the Russian and French crew members, making a three-person crew for the remainder of the government-funded occupation of the station. The subsequent Slovak mission could then be launched with the new crew and return with Padalka on TM28.

In the new year, the cosmonauts continued their science programme as news came in that the life of the station was to be extended three years (to 2002), if sufficient nonbudgetary (government) funds could be found. This allowed Energiya to tentatively plan a programme through to 2001. Just weeks later, the news came that the “private investor” had pulled out. The EO-27 crew launched in February 1999 were expecting to be the last crew to man the station.

Milestones

208th manned space flight 87th Russian manned space flight 80th manned Soyuz mission 27th manned Soyuz TM mission 26th Mir resident crew

33rd Russian and 71st flight with EVA operations

Avdeyev celebrates his 43rd birthday (1 Jan) on Mir – the third birthday he has spent in space (previously 1993 and 1996)

Flight Crew

BROWN Jr., Curtis Lee, 46, USAF, commander, 5th mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-66 (1994); STS-77 (1996); STS-85 (1997) LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 38, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-87 (1997)

ROBINSON, Stephen Kern, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-85 (1997)

PARAZYNSKI, Scott Edward, 37, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-66 (1994); STS-86 (1997)

DUQUE, Pedro Francisco, 35, civilian, mission specialist 3 MUKAI, Chiaki, 46, civilian, payload specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-65 (1994)

GLENN Jr., John Herschel, 77, US Senator, payload specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: Mercury 6 (1962)

Flight Log

John Glenn, the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth in 1962, had always wanted to return to space. But he had not expected that it would take over 36 years for him to do so. While pursing a business and political career, Glenn had always maintained a close relationship with NASA and had convinced NASA administrators that a set of medical experiments looking at the effects of microgravity on an older person would be of benefit to the near – and long-term goals of the agency. It would also provide an interesting set of comparison data with that taken during his first flight in 1962. Glenn first approached NASA with the idea in 1996, but it took two years to develop the experiment programme and obtain formal authorisation. The flight was also a public relations triumph for the space agency and a swansong of Glenn’s career in public life.

|

|

US Senator and former Mercury astronaut John H. Glenn Jr., equipped with sleep-monitoring equipment, floats near his sleep station on the mid-deck of Discovery

The launch progressed smoothly, with only minimal delays caused by a master alarm in the cabin and an aircraft infringement in the restricted airspace around KSC. After the ignition of the three main engines and prior to SRB ignition, the drag chute compartment door fell off, but this never posed a problem for the mission. It was decided that the drag chute would not be deployed during landing rollout.

The primary objective of the flight was a suite of over 80 experiments in the SpaceHab module. These focused on medical and materials research and a series of life sciences investigations that were sponsored by NASA and the space agencies of Canada, Europe and Japan (hence the inclusion of Duque and Mukai on the crew). The latter included cardiovascular studies, sleep studies and blood research. The investigations conducted by and on John Glenn provided useful data that would help to understand the process of aging in humans. The aging process and long space flights have similar common physiological effects and it was felt that information from Glenn and the other astronauts would help not only with long-duration space flight countermeasures, but also to identify early signs of aging and deterioration, which would assist in understanding the process and help in the development of countermeasures for the aging process on Earth. Like all former NASA astronauts, Glenn had been undertaking regular annual physicals at JSC since leaving the programme. These examinations have built up into an impressive database of biomedical studies of space explorers to see what changes, if any, occur as a result of space flight. Glenn’s flight at the age of 77, some 36 years after his first flight, was a unique opportunity to expand this data base. His experiments focused on how the absence of gravity affects balance and perception, the immune system response, bone and muscle density, metabolism and blood flow, and sleep.

The flight also included a range of studies on fish and plant specimens and a programme of microgravity materials studies in agriculture, medicine and manufacturing. During the mission, the crew also released a Petite Amateur Naval Satellite (PANSAT), which tested innovative technologies to capture and transmit radio signals normally lost because the original signal was too weak. The Hubble Space Telescope Orbital System Test provided an on-orbit test bed for hardware that would be used during the third Hubble service mission in 1999. The SPARTAN 201 free-flyer was released between FD 4 and 6, carrying a set of re-flight experiments from the 1997 STS-87 mission, with instruments to study the solar corona and gather data on the solar wind. Also located in the payload bay was a Hitchhiker Support Structure (HSS) with six experiments which had solar, terrestrial and astronomical objectives, to obtain data on extreme UV radiation on the sun and atmosphere. A UV spectrograph telescope was included to obtain information on extended plasma sources, such as hot stars and the planet Jupiter.

There were concerns over Glenn’s health on both his missions, the first because he was venturing into the unknown and the second over his age. But he had maintained a fine physical condition throughout his life. Upon entering space in 1962, Glenn commented: “Zero-G and I feel fine,’’ and 36 years later he said that he still felt the same way. When he returned to Earth at the end of STS-95, his comment was: “One-G and I feel fine.’’

Milestones

209th manned space flight

122nd US manned space flight

92nd Shuttle flight

25th flight of Discovery

12th SpaceHab mission (7th single module)

1st flight of SSME Block II engines

Glenn becomes oldest person to fly in space, aged 77

|

Int. Designation

|

N/A (launched on STS-108)

|

|

Launched

|

5 December 2001

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

19 June 2002 (aboard STS-111)

|

|

Landing Site

|

Edwards AFB, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

STS-108

|

|

Duration

|

195 days 19hrs 38 min 12 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Skif (Scythian)

|

|

Objective

|

ISS-4 expedition programme

|

Flight Crew

ONUFRIYENKO, Yuri Ivanovich, 40, Russian Air Force, ISS-4 and Soyuz TM commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM23 (1996)

BURSCH, Daniel Wheeler, 44, USN, ISS-4 flight engineer 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-68 (1994); STS-77 (1996)

WALZ, Carl Erwin, 46, USAF, ISS-4 flight engineer 2, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-65 (1994); STS-79 (1996)

Flight Log

The fourth expedition featured an experiment programme of 26 US and 28 Russian experiments in the fields of bioastronautics research, physical sciences, space product development, fundamental space biology, Earth observations, education and technology. Many of these experiments were carried over from previous expeditions.

During their stay aboard the station, the crew performed three EVAs. The first two (14 Jan for 6 hours 3 minutes and 25 Jan for 5 hours 59 minutes) were conducted from the Pirs facility on the Russian segment. The final one (20 Feb for 5 hours 47 minutes) was conducted out of the Quest airlock on the American segment. During the first EVA, Onufriyenko and Walz relocated the cargo boom for the Strela crane from PMA-1 to the outside of Pirs. An amateur radio antenna was also installed on Zvezda. EVA-2 saw Onufriyenko and Bursch install six deflector shields on the Service Module thrusters, install a further antenna and retrieve various science packages from Zvezda. The final EVA was conducted by the two American members of the ISS-4 crew on the 40th anniversary of the first flight of John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. Walz and Bursch performed the EVA from the Quest airlock, the first without a docked Shuttle in support. The objective was to prepare the area for installation of the S0 Truss during STS-110 in April 2002, relocating the tools to be used and inspecting the exterior of the station.

|

The ISS-4 inside the US Destiny lab. L to r Walz, Onufriyenko, Bursch

|

During the mission, the crew would oversee the upgrading of software as well as receiving the Progress Ml-8 re-supply craft. Their visitors arrived on the STS-110 mission that delivered the S0 Truss assembly and on the Soyuz TM33 Taxi mission. Prior to the arrival of Soyuz TM34, the crew had to relocate TM33 from the nadir port of Zarya to redock with the Pirs docking port.

The crew experienced several power problems and a number of failures of the Elektron oxygen generator. To conserve oxygen reserves in the tanks of Quest, the crew resorted to burning solid fuel oxygen generators in the Zvezda module while they attempted repairs to Elektron. This took several days during May. They also experienced difficulties with the operation of the Canadarm2, including the failure of the wrist roll joint, which would require replacement.

They were relieved on the station in June by the ISS-5, who arrived on STS-111, the mission that would take the ISS-4 crew back to Earth. Both the Americans in the ISS-4 crew surpassed Shannon Lucid’s previous US space flight endurance record (188 days), eventually clocking 196 days. In their careers, both men had flown four times and by the end of their ISS mission, Walz had logged 231 days in space while Bursch had accumulated 227 days. Onufriyenko had also completed two long missions and brought his experience to 389 days by the end of this one.

Milestones

4th ISS resident crew

3rd ISS EO crew to be launched by Shuttle

1st EVA from Quest without a Shuttle docked to the station

|

Int. Designation

|

2006-028A

|

|

Launched

|

4 July 2006

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

17 July 2006

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Discovery/ET-119/SRB BI-126/SSME #1 2045; #2 2051; #3 2056

|

|

Duration

|

12 days 18hrs 37 min 54 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Discovery

|

|

Objective

|

Second and final return to flight mission; utilisation and logistics flight (ULF1.1); MPLM logistics flight and partial ISS resident crew member delivery

|

Flight Crew

LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 45, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-87 (1997); STS-98 (1998); STS-104 (2001)

KELLY, Mark Edward, 42, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-108 (2001)

FOSSUM, Michael Edward, 48, civilian, mission specialist 1 NOWAK, Lisa Marie, 43, USN, mission specialist 2 WILSON, Stephanie Diana, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3 SELLERS, Piers John, 51, civilian, mission specialist 4, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-112 (2002)

ISS-13 crewmember up only:

REITER, Thomas, 48, German Air Force, ESA mission specialist 5, ISS-13 flight engineer 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM22 (1995)

Flight Log

Bad weather again delayed the launch of the Shuttle on 1 and 2 July, but after a one – day stand down, the launch resumed and STS-121 lifted off on America’s 230th birthday, the first launch on Independence Day, Again the launch phase was dramatically caught on film and analysed for any serious debris impacts, Though some debris hits were noted, there were no serious impacts, Following the docking on 6 July, the crew relocated the Leonardo MPLM to the station, where 3,357 kg of logistics was transferred. This included a new heat exchanger, a new window and window seals for the Microgravity Science Glove Box, a US EMU suit, SAFER jet pack and personal items, and a new oxygen generator to be installed in Destiny, There was also a

|

After nine days of cooperative work, the crews of STS-121 and ISS-13 bid farewell to each other prior to the undocking of Discovery. In the foreground, Sellers says farewell to Reiter (ESA), who launched to ISS on STS-121 but remained on the station with the ISS-13 crew. At rear, Wilson says goodbye to ISS-13 cosmonaut Vinogradov

|

European Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for storage of experiment samples prior to return to Earth. The MPLM was relocated back in the payload bay of Discovery on 14 July, by which time it had been filled with 2,086 kg of experiment samples, broken equipment and trash.

Three EVAs by Sellers (EV1) and Fossum (EV2) were completed during the docked phase of the flight. EVA 1 (8 Jul for 7 hours 31 minutes) included fitting a protection device for power, data and video cables on the S0 Truss. By routing cables through the Interface Umbilical Assembly, they could move the MT railcar to replace the trailing umbilical system with its power and data cable that had been inadvertently severed late in 2005. The astronauts then evaluated the RMS with the Orbiter Boom Sensor System, for potential use as a work platform during EVA to repair the damaged orbiter if required. EVA 2 (10 Jul for 6 hours 47 minutes) saw the crew restore the MT to full operation, while EVA 3 (12 Jul for 7 hours 11 minutes) focused on testing repairs on the Thermal Protection System Reinforced Carbon-Carbon panels, part of the evaluation of repair techniques that may be available to effect orbital repairs on future Shuttle missions. Photography of the samples (together with that of an area of Discovery’s port wing) was conducted. These images would be returned to Earth for detailed analysis. The astronauts also relocated a fixed grapple bar on the integrated cargo carrier in the payload bay to a position on the ammonia tank inside the SI Truss assembly, so that it could be moved by a future EVA crew at a later date.

Thomas Reiter had formerly exchanged to the ISS-13 crew shortly after the hatches between the vehicles had opened, moving his Soyuz seat liner into the DM of Soyuz TMA8. The more formal farewells occurred shortly prior to closure of the hatches and undocking of the Shuttle on 15 July. The two spacecraft had been docked for over 9 days, a day longer than planned as the mission was extended by a day to accommodate the third EVA. A final check of the surfaces of Discovery revealed nothing of concern and the safe re-entry and landing two days later gave an added boost to mission planners, eager to resume station construction with the next Shuttle mission.

Milestones

248th manned space flight 145th US manned space flight 115th Shuttle mission 32nd flight of Discovery 18th Shuttle ISS flight

58th US and 97th flight with EVA operations

6th Discovery ISS mission

7th MPLM flight

4th flight of MPLM-1 Leonardo

1st US launch on 4 July

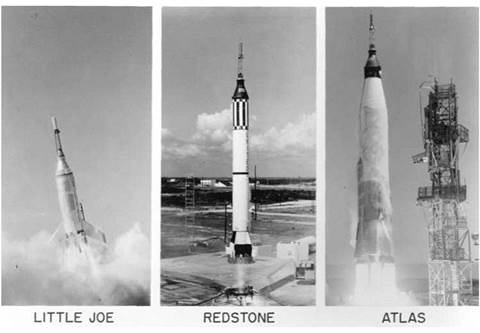

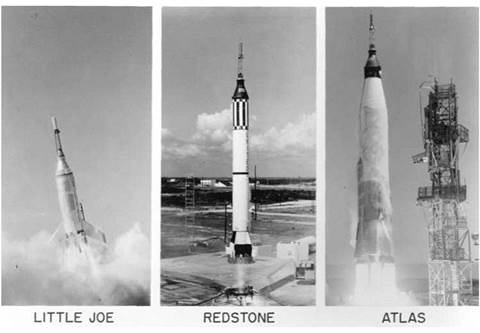

The first US astronauts, Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom, flew sub-orbital Mercury test flights in 1961 aboard Redstone rockets, reaching over 160 km (99 miles) altitude. They were recognised as astronauts. When a Soviet Soyuz R7 booster failed in 1975,

|

Mercury launch vehicles

|

causing the abort that led to Soyuz 18-1 making a sub-orbital flight to about 145 km (90 miles) altitude, the flight was credited as a “space flight” to the two cosmonauts.

The Redstone was the USA’s first intermediate-range ballistic missile and was powered by one Rocketdyne A-7 engine, with a thrust of 35,380 kg (78,013 lb) burning liquid oxygen, ethyl alcohol and water. The Mercury-Redstone was 25.29 m (82.97 ft) high. Two such vehicles were used in the Mercury programme for manned flights, while a third was cancelled with the desire to press on to the first orbital manned flight using Atlas.

Vostok 1 weighed 4,726 kg (10,419 lb) and comprised a spherical flight module and an instrument section, shaped like a double cone, containing batteries and a retro-rocket. The total length of the spacecraft was 4.4m (14.4ft), with a maximum diameter of 2.43 m (7.97 ft). The habitable module was 2.3 m (7.55 ft) in diameter and weighed 2,240 kg (4,938 lb). Vostok was designed to support life for ten days in an orbit low enough to guarantee a re-entry due to natural decay in that period, in case of retro- rocket failure. The instrument section, weighing 2,270 kg (5,004 lb) and measuring

|

The first cosmonauts of Vostok and Voskhod -1 to r Komarov, Feoktistov, Gagarin, Leonov, Titov, Bykovsky, Tereshkova, Popovich, Belayev, Yegorov, Nikolayev (AIS collection)

|

2.25 m (7.38 ft) long, utilised the TDU 1 retro-engine, powered by nitrous oxide and an amine-based fuel, with a thrust of 1.6 tonnes and a burn time of 45 seconds. The flight module landed at 10m/sec (32.8 ft/sec) – enough to injure the passenger seriously – so the pilot ejected at a height of 7 km (4 miles) and parachuted separately to the ground, landing at a speed of 5m/sec (16.4 ft/sec). The Vostok capsule had been tested three times successfully in six attempts on Korabl-Sputnik 1-5 (known in the West as Sputnik 4, 5, 6, 9 and 10), four of which carried canine passengers. Another caninecarrying mission failed to reach orbit. Other missions were planned but were cancelled in favour of upgrading the spacecraft into what became Voskhod as an interim measure to compete with the US Gemini series of missions.

Voskhod was essentially a Vostok spacecraft without crew ejector seats and with a back-up retro-rocket pack on top. It also had a landing retro-rocket system. The spacecraft weighed 5,320kg (11,730lb), comprising the 2,900kg (1,802lb) flight Descent Module, a 2,280 kg (5,027 lb) Instrument Module and a 145 kg (320 lb) back-up retro-pack. It was 5 m (16 ft) high, with a maximum diameter of 2.43 m (8 ft). The back-up retro-rocket – needed because Voskhod’s orbit, higher than Vostok on the more powerful SL-4 booster, would not naturally decay in ten days in the event of retro-fire failure – had a thrust of 12 tonnes and comprised 87 kg (192 lb) of solid propellant. It resembled an inverted cup on top of the Descent Module. To enable a 0.2 m/sec (0.65 ft/sec) landing, compared with the Vostok landing speed of 8 to 10m/sec (26-32 ft/sec), a landing retro-rocket was added, deployed with the parachute so that it fired downwards in front of the Descent Module. Voskhod flew one unmanned test flight, Cosmos 47, six days before the first manned flight. Voskhod 2 weighed 5,683 kg (12,531 lb). The main difference compared with Voskhod 1 was the flexible airlock, which was approximately 2.13 m (7 ft) long and 0.91 m (3 ft) in diameter. This was jettisoned after the EVA. The payload fairing of the SL-4 launch vehicle was modified to include a blister-like covering for the stowed airlock which protruded slightly from the flight capsule. Again, an unmanned craft (Cosmos 57) flew three weeks before Voskhod 2. There was also a 22-day canine flight flown as Cosmos 110 in early 1966, and a series of other manned Voskhod flights were planned, but they were cancelled in a desire to move on to the more advanced Soyuz programme.

Mercury

The US Mercury capsule was even smaller, with the pilot “putting it on”, rather than getting into it, as some astronauts described the entry. It would splashdown at sea under a single parachute.

The Mercury capsule was a bell-shaped spacecraft, 2.87 m (9.41ft) high, with a maximum diameter across the heat shield base of 1.85m (6.07 ft). At lift-off, with a launch escape system tower on its top, Mercury weighed about 1,905 kg (4,200 lb). The attitude of the heavily instrumented but severely cramped capsule would be changed by the release of short bursts of hydrogen peroxide gas from 18 thrusters located on the

|

The Original Seven Mercury astronauts pose by a Mercury capsule and an Apollo CM at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, during Look magazine’s coverage of the Collier Trophy Award in June 1963. L to r are Cooper, Schirra (partially hidden), Shepard, Grissom, Glenn, Slayton and Carpenter

|

craft. These movements could be controlled by the Automatic Stability and Control System (ASCS, which acted as the craft’s “autopilot” from the ground), through the Rate Stabilisation Control System (RSCS), or manually by the astronaut using a hand controller connected to a fly-by-wire system. At the back of the capsule, over an ablative heat shield, was a retro-pack containing three solid propellant rockets. These were held to the heat shield by three metal “straps” which were deployed along with the heat shield during re-entry. Mercury descended to a sea landing, or “splashdown” under one main parachute. Just before splashdown, the heat shield was dropped 1.21 m (4 ft), pulling out a rubberised fibreglass landing bag to reduce shock. Mercury had been tested unmanned 17 times previously on various rockets, only seven times successfully. Freedom 7 was Mercury capsule 7, the only first-production run, manrated capsule and the only one to fly manned with one circular porthole, rather than a larger rectangular window, one of several new features requested by the astronauts but not included in time for MR3. Mercury capsule No. 11 (for MR4 the second suborbital mission) was in fact the first operational capsule designed for orbital flights, and included a rectangular window and an explosive side hatch, recommended by the astronauts for safety purposes.

Both Vostok and Mercury made six single-person flights between 1961 and 1963. Mercury was succeeded by a larger two-person craft called Gemini, while Vostok basically became Voskhod, into which a three-man crew was crammed for the maiden flight in 1964. A second flight included the first spacewalk, performed in 1965. These two flights in a sense diverted the Soviet Union from its lunar goal, because they were flown for short-term prestige.

1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962 1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962

Pad 14, Cape Canaveral, Florida 3 October 1962

756.35 km northeast of Midway Island, Pacific Ocean Atlas 113D; spacecraft serial number SC-16 9 hrs 13 min 11 sec Sigma 7

Six-orbit mission

Flight Crew

SCHIRRA, Walter Marty Jr., 39, USN, pilot

Flight Log

Carpenter’s science-packed flight plan was being changed until almost launch day, so it was not surprising that he had trouble in orbit. One of his main critics was MA8 pilot Wally Schirra, who was extremely pleased with the smooth running of his own six-orbit mission, which he had made a modest engineering test flight with the minimum of experiments and manoeuvring. Indeed, his flight plan had been cast in stone on 8 August. What was surprising was the conservatism of mission planners, who decided to increase orbital flight experience by just 50 per cent, with a first-time landing in the Pacific Ocean, just short of a full six orbits.

MA8 could have been the first aborted launch, for just ten seconds after leaving the pad at 07: 15 hrs local time, Atlas 113D developed an alarming clockwise roll rate just 20 per cent short of an abort. The launch was the first to be shown on British television on the same day, three hours later, thanks to the Telstar communications satellite. It was also watched from the Cape by nine new NASA astronauts, who had been selected the previous month. Schirra had been in his capsule, with the engineering name Sigma 7, since 04: 14 hrs, and reached the highest Mercury orbit of 282 km (175 miles) and a speed of 28,256 kph (17,558 mph).

There had been concern that Schirra would be affected by the radiation belt created the previous July by the horrendous US upper-atmosphere nuclear test, Project Dominic. An overheating spacesuit almost forced an early return after just one orbit, but fortunately spacesuits were Schirra’s speciality. He deployed the MA7- type tethered multicoloured balloon, this time with success, and spent at least one orbit letting the spacecraft drift as it pleased. The retros were fired at T + 8 hours 56 minutes 22 seconds and Sigma 7 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 756.35 km (470 miles) northeast of Midway Island, and just 7.2 km (4 miles) from its target, close to the recovery ship, USS Kearsage. Schirra’s mission lasted 9 hours 13 minutes

|

Mercury Atlas 8 pilot Wally Schirra

|

11 seconds. He stayed with the ship until winched aboard the Kearsage. Media interest in the flight was minimal.

Milestones

9th manned space flight 5th US manned space flight 5th Mercury manned flight

|

|

|

Int. Designation

|

1981-034A

|

|

Launched

|

12 April 1981

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

14 April 1981

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 23, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Columbia/ET-2/SRB A07; A08/SSME #1 2007;

|

|

#2 2006; #3 2005

|

|

Duration

|

2 days 6 hrs 20 min 53 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Columbia

|

|

Objective

|

First manned orbital test flight (OFT-1) of Shuttle system

|

Flight Crew

YOUNG, John Watts, 50, USN, commander, 5th mission

Previous missions: Gemini 3 (1965); Gemini 10 (1966); Apollo 10 (1969);

Apollo 16 (1972)

CRIPPEN, Robert Laurel, 43, USN, pilot

Flight Log

The build up to this momentous space mission for the US programme was painfully slow. A budget lower than that afforded to Apollo for a space system five times more technically demanding resulted in inevitable glitches at almost every turn. The first space flight by the Space Shuttle was originally scheduled for 1978, but in fact all that happened was that the first four space crews were rather optimistically named for missions that would start the following year. Thus, veteran John Young and rookie Bob “Crip” Crippen began what was to become one of the longest periods of training ever, ending with a lift-off in 1981. Coincidentally, for such a major space milestone, the launch would be on the twentieth anniversary of the first manned space flight by Yuri Gagarin.

That the launch had been scrubbed at T — 36 min, by a computer synchronisation glitch two days before, which had been dubbed by the media assembled at the Kennedy Space Center as a “fiasco”, is indicative of the reputation of the Shuttle. The USA had been through a period of several major technical disasters, including Three Mile Island, and there were many cynics expecting to be reporting another from the Kennedy Space Center on a maiden flight being manned for the first time. There is no doubting the heroism of the crew, who had only the dubious opportunity of ejection seats available to them for an early bail-out.

The cataclysmic blast-off occurred at 07: 00 hrs local time, causing unpredicted over pressurisation of the orbiter and a potential collision with the launch tower, followed almost immediately by the roll programme which alarmed already nervous

The Third Decade: 1981-1990

spectators with its brute force. Thrust was five per cent higher than anticipated, leading to a steeper, “heads down” climb to orbit. The solid rocket boosters were ejected at T + 2 minutes 11 seconds and the three main engines cut off at T + 8 minutes. The Space Shuttle Columbia was in initial orbit and was then boosted by four burns of the orbiter’s own propulsion system. Inclination was 40.3° and maximum altitude 232 km (144 miles).

With Columbia flying “upside-down” with its back facing the Earth, the payload bay doors were opened, exposing a vast interior which was empty for this test flight. TV cameras also showed that some heatshield tiles were missing from the rear of the orbiter and much was made of this in the popular press. They were not critical tiles, but all the same if they were missing, could other more critical tiles on the orbiter’s underside be loose or lost? The crew would find out after their thirty-sixth orbit, when after an almost flawless orbital workout by the jubilant Young and Crippen, the OMS engines initiated the 2 minute 27 second long retro-fire burn.

The Mach 25 re-entry, during which some tiles were exposed to 1,260°C, was accompanied by the usual radio blackout. Then, at Mach 10 and 57.3 km (36 miles), the happy Young reported that all was well. He proceeded to bring Columbia in like an airliner, landing on the dry lake bed runway 23, at Edwards Air Force Base, with main gear touchdown at T + 2 days 6 hours 20 minutes 32 seconds. Routine space flight with airliner-like landings seemed to have begun. Fifty Shuttle flights a year were being predicted.

Milestones

80th manned space flight 32nd US manned space flight 1st Shuttle mission 1st flight of Columbia

1st manned space flight in a reusable spacecraft

1st manned space flight on previously untested spacecraft

1st manned space flight to be boosted by solid propellants

1st flight by crewman on fifth space mission

1st flight to end with conventional runway landing

Flight Crew

POPOV, Leonid Ivanovich, 35, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz 35 (1980)

PRUNARIU, Dumitru Dorin, 28, Romanian Army Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

The final Interkosmos mission involving a cosmonaut researcher from a Soviet bloc country, Soyuz 40, was also the last of this Soyuz model. Crewed by Leonid Popov and Dumitru Prunariu, the mission got under way at 23: 17hrs from Baikonur, followed by the docking with Salyut 6 a day later and greetings from residents Kovalenok and Savinykh. Experiments on board included those to study the Earth’s upper atmosphere and changes in its magnetic field. The mission ended at T + 7 days 20 hours 41 minutes 52 seconds, 224 km (139 miles) southeast of Dzhezkazgan. Maximum altitude during the 51.6° mission was 374 km (232 miles).

When Soyuz T4 returned later, Salyut 6 had received 16 cosmonaut crews and 15 unmanned spacecraft in three-and-a-half years. No fewer than 35 dockings had been made with it and Salyut 6 was occupied for 676 days. Some 13,000 photographs of the Earth had been taken and 1,310 experiments operated a remarkable record.

Milestones

81st manned space flight

49th Soviet manned space flight

42nd Soyuz manned space flight

39th (original) Soyuz manned space flight

Final flight of original Soyuz variant

1st manned space flight by a Romanian

9th and final Interkosmos mission

Prunariu (right) wears the Chibis lower body negative pressure garment aboard Salyut 6, assisted by Popov

|

Int. Designation

|

1985-034A

|

|

Launched

|

29 April 1985

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

6 May 1985

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-099 Challenger/ET-17/SRB BI-016/SSME #1 2023;

|

|

#2 2020; #3 2021

|

|

Duration

|

7 days 0 hrs 8 min 46 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Challenger

|

|

Objective

|

Spacelab 3 research programme

|

Flight Crew

OVERMYER, Robert Franklyn, 48, USMC, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-5 (1982)

GREGORY, Frederick Drew, 44, USAF, pilot LIND, Don Leslie, 54, civilian, mission specialist 1 THAGARD, Norman Earl, 41, civilian, mission specialist 2 THORNTON, William Edgar, 56, civilian, mission specialist 3 WANG, Taylor G., 44, civilian, payload specialist 1 VAN DEN BERG, Lodewijk, 53, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

Space Shuttle activities were building up to a frenetic pace by April 1985. Discovery was dispatched on mission 51-D, Challenger rolled out to the now vacant Pad 39A for 51-B, and the new orbiter Atlantis arrived at the KSC in preparation for its first mission later that year. It was all looking rather routine stuff, especially when 51-B finally got off the ground – 17 days after 51-D – with a seven-man crew that included three people over 50, as if to emphasise the apparent routine nature of manned space flight. NASA was pushing the system and time was running out. Spacelab 2 featured the Instrument Pointing System and a pallet-only development flight. It was delayed so much due to preparing the IPS that Spacelab 3 flew before it, adding to the confusing Shuttle identification sequence. Research on Spacelab 3, considered to be the first operational mission of the long series, focused on five disciplines: materials science, life sciences, fluid mechanics, atmospheric physics and astronomy. The flight featured 15 primary experiments, of which 14 were considered successful. The crew worked in two shifts: Gold (Gregory, Thagard, Van Den Berg) and Silver (Overmyer, Lind, Thornton, Wang).

Challenger lifted off just 2 minutes 18 seconds later than anticipated, after a liquid oxygen drain back had to be manually commanded, at 12: 02hrs local time.

|

(L to r) The STS 51-B crew of Gregory, Overmyer, Lind, Thagard, Thornton, Wang, and van den Berg. Note the different coloured shirts, denoting the two-shift operations

|

Apart from an overheating APU which had to be shut down, the launch was smooth and Challenger, in its 57° orbit which would reach a maximum altitude of 308 km (191 miles), was placed into a tail down, nose up gravity gradient attitude, vital for the array of mainly microgravity processing experiments to be operated inside the Space – lab 3 laboratory. The two payload specialists. Lodewijk van den Berg and Taylor Wang, both naturalised American citizens, operated their own crystal growth and fluid physics experiments, the latter only after spending days getting it to work following an electrical fault that almost spoiled years of hard work.

Also on board Challenger – another Shuttle first – were two monkeys and 24 rats, to help with the study of space adaptation syndrome, SAS, under the guidance of doctors Norman Thagard and William Thornton. The performance of the Animal Holding Facility left much to be desired and the astronauts spent a lot of time clearing up floating droppings. Two small research satellites were to be deployed from GAS canisters in the payload bay, but one failed to get away. Science astronaut Don Lind, having waited a record 19 years to get into space, marvelled at the sight of the aurora borealis from space.

The highly esoteric science mission, which went over most people’s heads, was extremely successful and ended with a long rollout on the Edwards Air Force Base desert runway 17, and with the heaviest cargo to return from space – 14,198 kg (31,307 lb) – at T + 7 days 0 hours 8 minutes 46 seconds. Further landings at the KSC had been banned after the 51-D landing incident.

Milestones

105th manned space flight 48th US manned space flight 17th Shuttle flight 7th flight of Challenger

Thornton retains oldest person in space record (56) 2nd Spacelab Long Module mission

|

Int. Designation

|

1990-002A

|

|

Launched

|

9 January 1990

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed 20

|

January 1990

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 22, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Columbia/ET-32/SRB BI-035/SSME #1 2024;

|

|

#2 2022; #3 2028

|

|

Duration

|

10 days 21hrs 0min 36 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Columbia

|

|

Objective

|

Satellite deployment and LDEF retrieval mission

|

Flight Crew

BRANDENSTEIN, Daniel Charles, 46, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 51-G (1985)

WETHERBEE, James Donald, 37, USN, pilot

DUNBAR, Bonnie Jean, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 61-A (1985)

IVINS, Marsha Sue, 38, civilian, mission specialist 2 LOW, George David, 33, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

When the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) was deployed in 1984, the plan was that it would be retrieved the following year. The NASA Space Shuttle manifest got itself into a real pickle under pressure from all directions and had to push the LDEF retrieval mission into September 1986. That would have been flight STS 61-L, commanded by Don Williams, piloted by Mike Smith-who was also assigned to 51-L Challenger – and with mission specialists Bonnie Dunbar, James Bagian and Manley Carter. After the Shuttle programme had recovered from the Challenger accident, the LDEF retrieval mission was assigned to STS-32 with the lone survivor from 61-L, Bonnie Dunbar. The commander of what was going to be one of the more high-profile Shuttle missions was the new chief of the astronauts, Dan Brandenstein.

STS-32 was subject to several delays, partly due to the longer time in getting the orbiter Columbia spaceworthy. Eventually, Columbia was rolled out to Pad 39A just after the launch of STS-33 and would be the first Shuttle to take off from this refurbished pad since STS 61-C in January 1986. It was set for a mammoth ten-day mission, starting on 18 December and taking in a Christmas in space, but problems bringing the new pad on line for launches meant a delay first to 21 December, then for three weeks to 8 January. NASA felt it prudent to give the launch and support teams a full holiday.

|

STS-32 retrieves LDEF after almost six years in space

|

As the crew left their quarters on 8 January, they knew they would be coming back the same day because the weather gave them less than a ten per cent chance of taking off. Going through a full countdown to T — 5 minutes, however, provided a good opportunity to give Pad 39A a full workout. The following day, Columbia took off at 07: 35 hrs local time, featuring in one of the most beautiful lift-offs of a Shuttle, making a direct insertion burn to 28.5° orbit. On day two, the Shuttle’s major payload on the upward journey, Syncom IV, or Leasat 5, was deployed, and Columbia sailed on towards its dramatic meeting with the LDEF. There was a serious water leak on the third day, involving the collection of two gallons of water globules.

The complicated LDEF rendezvous was completed on the fourth day, 12 January, when Columbia flew towards, over and down to the facility, with its payload bay

doors opening towards the Earth, waiting to receive. While Brandenstein deftly manoeuvred the Shuttle as it had never been manoeuvred before, Dunbar got ready with the RMS robot arm, which she was operating using a monitor showing scenes from the TV camera at its end. Brandenstein stopped all motion and, as rehearsed hundreds of times, Dunbar made the great space catch. As pilot Jim Wetherbee flew Columbia belly first, the LDEF was manoeuvred into several positions while the other mission specialists, David Low and Marsha Ivins, took close up photographs of every part, just in case the LDEF could not be safely secured in the payload bay and had to be left in space. Following the style of the mission, LDEF was berthed in the payload bay later, after 2,093 days autonomous flying in space, pitted, torn and worn. Columbia continued on its winning way, with the crew busying themselves with an array of science experiments, a range of medical experiments under the Extended-Duration Orbiter Medical Programme (EDOMP) and Dunbar getting the news that her husband (Ronald Sega) had been selected for astronaut training.

The landing on the ninth mission day was called off by a failure of one of the suite of five computers on board, and as a result, Columbia returned to Edwards Air Force Base on runway 22 at night, and after a Shuttle-record mission lasting 10 days 21 hours 0 minutes 36 seconds – the longest five-crew space flight, and with the heaviest landing weight of 103,572 kg (228,376 lb). STS-32 was probably the most complicated space flying mission and certainly the most successful and rewarding, as scientists pored over the LDEF to see how its time in space had affected its array of different materials.

Milestones

130th manned space flight 63rd US manned space flight 33rd Shuttle mission 9th flight of Columbia

Brandenstein celebrates his 47th birthday in space (17 Jan)

Flight Crew

SOLOVYOV, Anatoly Yakovlovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM5 (1988)

BALANDIN, Aleksandr Nikolayevich, 36, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

What was planned as a now-standard five month residency aboard the Mir complex began at 07: 16 hrs local time at Baikonur on 11 February, when Soyuz TM9 lifted off, watched by US astronaut guests Dan Brandenstein, Paul Weitz, Ron Grabe and Jerry Ross. Docking was completed two days later and, yet again, was a manual affair, with the automatic approach malfunctioning at the last moment. The TM9 cosmonauts, Anatoly Solovyov and Aleksandr Balandin, joined Aleksandrs Viktorenko and Serebrov for the traditional handover period. The TM9 residency began officially on 19 February and was due to last until 30 July, following the 22 July launch of Soyuz TM10.

The TM9 crew were expected to receive the second large add-on module, Kristall, in April and begin an intensive programme of materials processing, so that they could return to Earth with 100 kg (221 lb) of space products to make a profit of 25 million roubles from the 80 million rouble space flight. Thus, the space flight could be seen as actually contributing to the economy and not as wasteful and extravagant as it was regarded by much of the Soviet public.

As Soyuz TM9 approached Mir, TV pictures, seen on the national news, revealed that the thermal insulation blankets around the flight cabin had become unclipped. The Soviets routinely announced that at some time during the mission the crew would have to make an unscheduled spacewalk to clip them back on. No fuss was made of the event. After settling into the routine of life aboard Mir, TM8 cosmonauts Viktorenko and Serebrov left them to it, and the routine continued with the docking of the Progress M3 supply ship on 3 March.

|

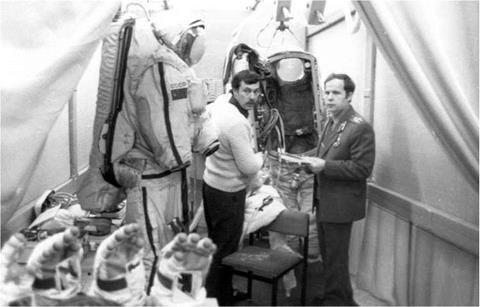

Solovyov (right) and Balandin reviewing EVA equipment and hardware during training

|

The mission proceeded very quietly, but the scheduled launch date for Kristall passed before the Soviets announced that the new module had been delayed yet again, this time until June. The crew which had trained especially to operate Kristall would only have about two months to do so, rather than the planned four months. Progress 42, the last of the original spacecraft first launched in 1978, docked to Mir on 8 May and later in the month, the most bizarre case of inaccurate and distorted media hype of the space age occurred when Aviation Week magazine “discovered” the already three – month-old story of the unclipped insulation, leading the western press to print stories of the cosmonauts being stranded in space. If there had been any danger, the Soviets would have launched an unmanned replacement ferry immediately, rather like they did with Soyuz 34 which replaced Soyuz 32 during the Salyut 6 mission of 1979. The delayed Kristall was at last launched on 31 May but at first failed to dock when a computer fouled up during the final approach. It finally moored at Mir on 10 June.

Because of the delay to the launch of Kristall, the Soviets decided to extend the TM9 mission from 29 July to 9 August and to delay the launch of the replacement TM10 from 22 July to 1 August. On 1 July, Solovyov and Balandin made a 7 hour EVA to clip back the loose insulation on their TM9 ferry. They used the Kvant 2 airlock and while exiting, opened the outer hatch before the airlock had fully depressurised. It flew open with such a force that it almost came off its hinges. Not surprisingly, after their tortuous record-breaking EVA, scrambling over the Soyuz and successfully re-clipping only two of the three insulation panels, the cosmonauts couldn’t close the hatch properly and were forced to depressurise the rest of Kvant to gain entry to Mir. Another spacewalk, lasting three hours on 26 July, closed the hatch but did not completely seal it.

It would be left for the TM10 crew to do the necessary repairs. Its cosmonauts, the “two Gennadys”, Manakov and Strekalov, arrived on Mir on 3 August, and on 9 August as advertised, Solovyov and Balandin routinely ended their mission, making a mockery of the media hype the previous June. The mission lasted 179 days 2 hours 19 minutes.

Milestones

131st manned space flight

68th Soviet manned space flight

61st Soyuz manned mission

8th Soyuz TM manned mission

16th Soviet and 39th flight with EVA operations

Baladin celebrates his 37th birthday in space (30 Jul)

1996-001A 11 January 1996

1996-001A 11 January 1996

1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962

1962 beta delta 1 3 October 1962