STS-2

|

Int. Designation |

1981-111A |

|

Launched |

12 November 1981 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

14 November 1981 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 23, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-3/SRB A09; A10/SSME #1 2007; #2 2006; #3 2005 |

|

Duration |

2 days 6 hrs 13 min 13 sec |

|

Callsign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

Second Orbital Test Flight (OFT-2); tests of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) |

Flight Crew

ENGLE, Joseph Henry, 49, USAF, commander TRULY, Richard Harrison, 44, USN, pilot

Flight Log

As Columbia was being prepared for its second mission, originally scheduled for 10 September then pushed to 30 September, with 1,000 new tiles, new RCS components, an OMS nozzle and fuel cells, nitrogen tetroxide leaked from a ruptured fuel line during propellant loading, damaging another 240 tiles on its nose. The launch was postponed to 4 November. Things looked good but the launch was delayed for 2 hours 40 minutes and finally scrubbed, holding at T — 31 seconds, when an oil flush on one of the APUs failed and a computer malfunctioned. Both had to be replaced before a new launch attempt, eight days later.

The first flight of a re-used manned spacecraft began at 10: 10 hrs local time and astronauts Joe Engle and Richard Truly (marking a space first by being launched on his birthday) were at last on their way, into a 38° inclination orbit which would have a maximum altitude of 219 km (136 miles). A five day flight was on the agenda, with a complement of science experiments and the testing of the Remote Manipulator System robot arm, being carried for the first time. An increase in the alkaline level of the electrolyte in one of Columbia’s three fuel cells spoiled the day for Engle and Truly, who were told to cram five days work into two, as mission rules dictated.

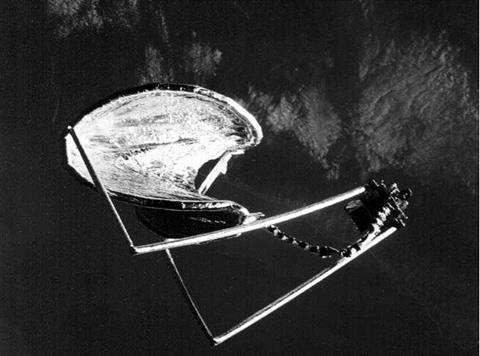

The RMS did not work quite as well as planned since it suffered a back-up drive failure, but TV cameras at its end gave interesting views of the payload bay and other parts of the Shuttle. Engle did not get the chance to try out the Shuttle EVA suit inside the airlock. Mission scientists were pleased with the results from the science experiments, particularly the multi-spectral imaging radiometer and the Shuttle Imaging Radar. Columbia came home on the dry lake bed runway 23 at Edwards Air Force

|

The launch of STS-2 sees Columbia become the first manned spacecraft to return to orbit |

Base, touching down at a speed of 361 kph (224 mph), at T + 2 days 6 hours 13 minutes 13 seconds, main gear touchdown time.

Milestones

82nd manned space flight

33rd US manned space flight

2nd Shuttle flight

2nd flight of Columbia

1st manned space flight by reused spacecraft

Truly celebrates his 44th birthday by being launched into space (12 November)

SOYUZ T13 |

|

Int. Designation |

1985-043A |

|

Launched |

6 June 1985 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan |

|

Landed |

26 September 1985 |

|

Landing Site |

220 km northeast of Dzhezkazgan |

|

Launch Vehicle |

R7 ( 11A511U2) spacecraft serial number (7K-ST) # 19L |

|

Duration |

112 days 3hrs 12min 6 sec (Dzhanibekov) 168 days 3 hrs 51 min 0 sec (Savinykh – returned in Soyuz T14) |

|

Callsign |

Pamir (Pamirs) |

|

Objective |

Salyut 7 rescue and recovery mission |

Flight Crew

DZHANIBEKOV, Vladimir Aleksandrovich, 43, Soviet Air Force, commander, 5th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz 27 (1978); Soyuz 39 (1981); Soyuz T6 (1982); Soyuz T12 (1984)

SAVINYKH, Viktor Petrovich, 43, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz T4 (1981)

Flight Log

After the return of the long-duration Soyuz T10 trio from the Salyut 7 space station in late 1984, another three manned missions were planned for 1985/1986 to continue manned operations. Indeed, the crews had been selected and were in training. Soyuz T13 would be launched in May, crewed by Vladimir Vasyutin, Viktor Savinykh and Aleksandr Volkov to complete a six-month mission. They would be visited by Soyuz T14, carrying an all-female crew on a two-week mission in November. This crew would comprise commander Svetlana Savitskaya on her third mission, along with Yekaterina Ivanova and Yelena Dobrokvashina. The Soyuz T15 flight would then launch at the end of 1985 to complete the Salyut 7 programme by the spring of 1986, when a new station would have been launched. Soyuz T15 was to have been crewed by Viktor Viktorenko, Alexandr Alexandrov and Yevgeny Salei.

Then, in early 1985, came the blow that Salyut 7 was effectively dead in space. Contact had been lost and the space station was out of control. Systems were freezing and observers expected that it would never be manned again. There was concern that it would make a Skylab-like uncontrolled re-entry. It was decided to send the most qualified veteran cosmonaut (Vladimir Dzhanibekov, with four previous space flights to his credit) to the station along with veteran Salyut 6 FE Savinykh to see if they could restore the station to operational use. Dzhanibekov had already proven his

|

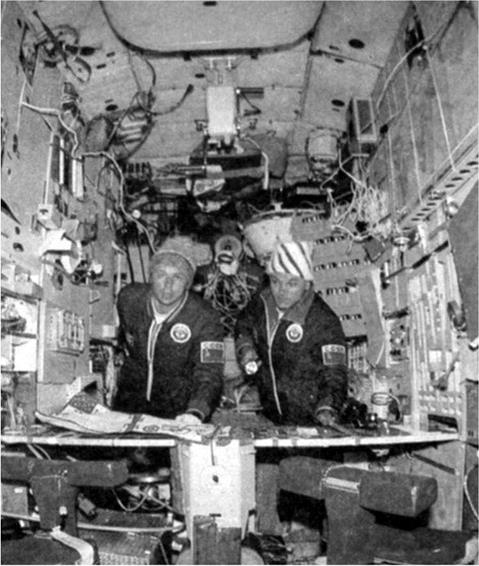

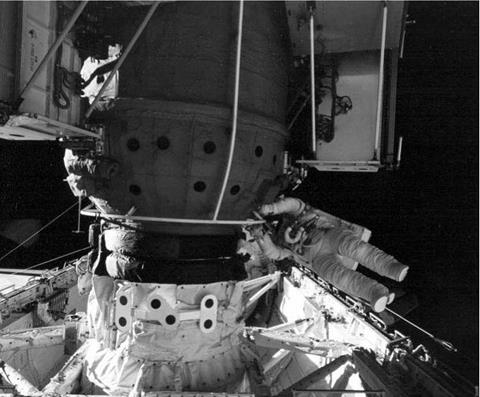

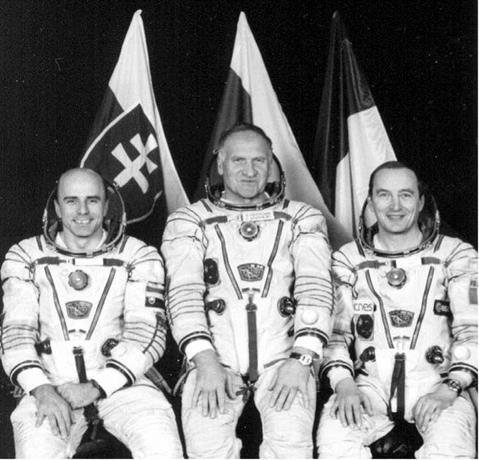

Savinykh and Dzhanibekov wearing thermals during the early occupation of the stricken space station |

docking skills in past missions, and all his knowledge would be required on this demanding space flight. If the two men could restore the station sufficiently, then the Soyuz T14 crew would be sent to Salyut to resume their intended programme. Flying along with the T14 crew would be Salyut veteran Georgi Grechko, on a short science – orientated mission. He would return with Dzhanibekov after a few days on the Salyut.

The fate of the other crews would be decided if Salyut could be restored. The launch of Soyuz T13 at 12:40 hrs local time from Baikonur on 6 June to conduct “joint work” with Salyut 7 caught western observers by surprise. The two cosmonauts, Vladimir Dzhanibekov – the first Soviet to make five space flights – and flight engineer Viktor Savinykh, proceeded to fly one of the bravest and most remarkable space missions ever.

Soyuz T13 arrived at Salyut two days later, flying all around to check the condition of the exterior and finally docking at the front port with the aid of a new laser ranging device. The crew donned oxygen masks and lots of woolly clothing and entered the freezing space station. Salyut was stabilised so that its solar panels were pointing at the Sun for long enough periods to re-start some form of electrical power. The station’s life support system was fixed thanks to expert repairs by the two crewmen, who often retreated to Soyuz to warm their bodies. Communications directly from the station were restored and by late June, Salyut 7 was declared to be in an operational state.

Progress 24 arrived on 23 June with additional repair and replenishment supplies, and the crew even got to work on some experiments dedicated to Earth observation, while Progress loaded the Salyut propulsion system with fuel. Confounding experts who regarded the Soyuz T13 mission as finished, the Soviets launched a Heavy Cosmos module, rather than the Progress-class spacecraft that it was first suspected to be by analysts. Designated Cosmos 1669, it docked with Salyut on 21 July, enabling even more fruitful work to be conducted by the remarkable crew, which even went on EVA on 2 August to place two small solar arrays on the third large array on Salyut. The walk lasted about 5 hours.

Cosmos 1669 undocked on 28 August, making a controlled re-entry two days later, and the T13 crew went on conducting a mission as ordinary and routine as a normal residency. The 51.6° mission reached a maximum altitude of 359 km (223 miles). Soyuz T14 was launched and joined them on 18 September. Dzhanibekov and one of the T14 crew, the burly Georgy Grechko, undocked on 25 September, flew a day’s autonomous mission and came home – the first individual space travellers who were launched separately but landed together – at T13 flight time of T + 112 days 3 hours 12 minutes. Savinykh, meanwhile, remained on board Salyut 7 to attempt the longest manned space flight in history, only to be thwarted by his new commander’s illness.

Milestones

106th manned space flight

58th Soviet manned space flight

51st Soyuz mission

12th Soyuz T mission

1st reactivation of a dead space station

10th Soviet and 31st flight with EVA activities

STS-36 |

|

Int. Designation |

1990-019A |

|

Launched |

28 February 1990 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

4 March 1990 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 23, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-33/SRB BI-036/SSME #1 2019; |

|

#2 2030; #3 2027 |

|

|

Duration |

4 days 10 hrs 18 min 22 sec |

|

Callsign |

Atlantis |

|

Objective |

6th classified DoD shuttle mission |

Flight Crew

CREIGHTON, John Oliver, 45, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 51-G (1985)

CASPER, John Howard, 46, USAF, pilot

MULLANE, Richard Michael, 45, USAF, mission specialist 1, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 41-D (1984); STS-27 (1988)

HILMERS, David Carl, 40, USMC, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-J (1985); STS-26 (1988)

THUOT, Pierre Joseph, 34, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

This DoD classified military mission by the orbiter Atlantis was always going to be a quiet affair, other than the usual comical revelation of exactly what the classified payload was going to be. In this case, it was a digital imaging and electronic signals intelligence satellite, which was to be deployed on the Shuttle’s eighteenth orbit, comparatively late in the proposed four-day mission, by a new system called the Stabilised Payload Deployment System, SPDS. This was fixed to the payload in the payload bay before launch and was to be used to rotate the satellite clear of the Shuttle before release by spring-loaded pistons.

Another innovation for the mission was its high inclination of 62°, ostensibly 5° over the safety limits for launches from the Kennedy Space Center, but on a trajectory which would not quite take it over land. As if to veil this fact as much as possible, Atlantis was first scheduled for a night launch on 16 February, which was eventually moved to 22 February, at 01: 00hrs local time. Before the crew could board the Shuttle, however, the weather caused concern and for the first time since Apollo 9, a US mission was delayed by the illness of the crew. In this case, it was commander John Creighton, who was suffering from an upper respiratory tract infection.

|

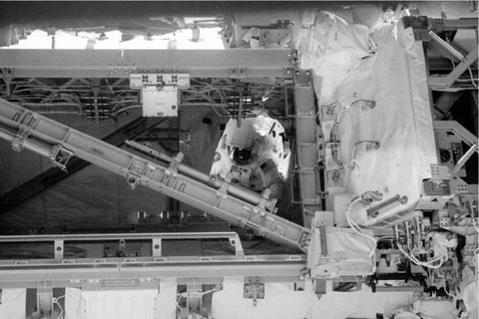

Commander Creighton photographs views out of the overhead windows of Atlantis |

His illness delayed the launch until 25 February and the count reached T — 31 seconds when a range safety computer went on the blink. By the time it had been fixed, the liquid oxygen was too cold for the SSMEs. The launch was cancelled the following day due to winds at altitude and a low cloud deck and was routinely postponed for 48 hours. On 28 February, the weather looked to win again, but with just seconds of the launch window remaining, Atlantis lit up the night sky at 02: 50 hrs local time, heading for its unique launch azimuth. Deployment of the classified satellite took place as planned and the mission ended quietly with a landing at Edwards Air Force Base at T + 4 days 10 hours 18 minutes 22 seconds.

It was revealed later that the satellite had apparently broken apart in orbit and two of the six resulting fragments had re-entered soon after. The satellite may have failed to fire its rocket stage to reach operational orbit. All in all, it seems that STS-36 was an expensive waste of a mission.

Milestones

132nd manned space flight 64th US manned space flight 34th Shuttle flight 6th flight of Atlantis

STS-49 |

|

Int. Designation |

1992-026A |

|

Launched |

7 May 1992 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

16 May 1992 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards AFB, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-105 Endeavour/ET-43/SRB BI-050/SSME #1 2030; #2 2015; #3 2017 |

|

Duration |

8 days 21 hrs 17 min 38 sec |

|

Call sign |

Endeavour |

|

Objective |

Capture, repair and redeployment of stranded satellite INTELSAT VI (F-3); Assembly of Space Station by EVA Methods demonstration (ASSEM) |

Flight Crew

BRANDENSTEIN, Daniel Charles, 49, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 51-G (1985); STS-32 (1990)

CHILTON, Kevin Patrick, 36, USAF, pilot

HIEB, Richard James, 36, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991)

MELNICK, Bruce Edward, 42, US Coast Guard, mission specialist 2,

2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-41 (1990)

THUOT, Pierre Joseph, 36, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-36 (1990)

THORNTON, Kathryn Cordell Ryan, 39, civilian, mission specialist 4, EV3, 2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-33 (1989)

AKERS, Thomas Dale, 40, USAF, mission specialist 5, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-41 (1990)

Flight Log

The maiden flight of the Endeavour (the replacement orbiter for Challenger which was lost in the 1986 launch accident) was an impressive mission that clearly demonstrated the value of having astronauts on board to overcome technical problems. Whether there was a need for Endeavour itself was a question long debated, but it was the loss of Challenger that finally secured the construction of the new vehicle from the structural spares that had been factored into the orbiter construction programme several years before. There was no such contingency to replace Columbia seventeen years later.

|

|

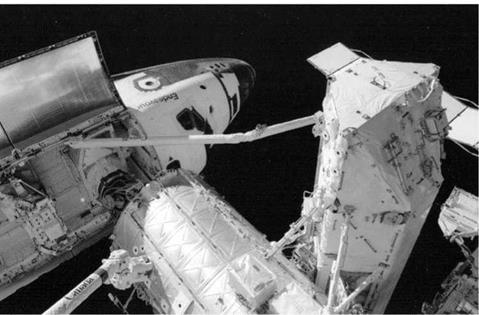

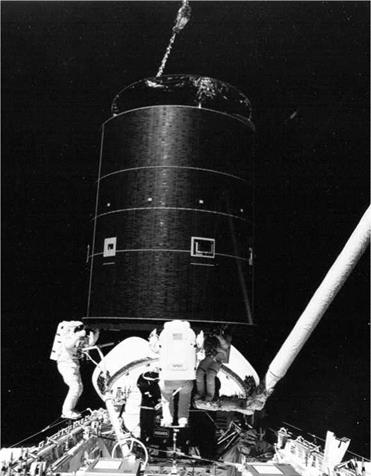

Three astronauts hold onto the 4.5-ton Intelsat VI satellite after completing a six-handed “capture”. L to r are astronauts Hieb, Akers and Thuot, who stands on the end of the RMS. This first three-person EVA was the third attempt at grappling the satellite

Following the 6 April 1992 flight readiness firing of Endeavour’s three main engines, the management team decided to replace all three due to irregularities that had arisen in two of the high-pressure oxidiser turbo-pumps. The launch of STS-49 was set for 4 May, but was rescheduled for 7 May, with an early launch window that would offer better lighting conditions for photo-documentation of the behaviour of the new vehicle during its first ascent. The lift-off on 7 May was delayed by 34 minutes due to bad weather at the transoceanic abort landing site, as well as technical problems with one of Endeavour’s master event controllers.

The primary objective of the flight was the capture and redeployment of the Intelsat VI satellite that had been launched aboard a Titan rocket on 14 March 1990.

During the launch, the second stage of the Titan had not separated, preventing the satellite’s ascent into a geosynchronous orbit. Quick thinking by ground controllers triggered the separation of the satellite from the unused Perigee Kick Motor (PKM) that was still attached to the Titan stage, and careful use of onboard liquid propellant allowed the satellite to reach a thermally stable 299 x 309 nautical mile orbit. Subsequent data analysis suggested it would be more cost-effective to bring a new kick motor up to the stranded satellite on the Shuttle than to return it to the ground and relaunch it. The Hughes Aircraft Company’s Space and Communications Group worked with NASA to construct special hardware to support the EVA operations that would be required.

The crew split into two EVA teams. Thuot (EV1) and Hieb (EV2) were termed the Intelsat EVA crew for the satellite retrieval and redeployment, while Thornton (EV3) and Akers (EV4) would work on the planned evaluation of space station construction techniques. A specially designed capture bar would be used to capture the satellite but in the event, this did not work as planned. During the first attempt on 10 May, Thuot had been unable to attach the capture bar, causing the satellite to bounce away and tumble at even greater rates the more he tried. The following day, the rotation of the satellite had slowed sufficiently for Thuot to gently move the bar into place. This time, however, the latches on the bar failed to fire, causing the satellite to drift off once again. It became evident that the planned method of capture would not work and during 11 May, as the crew rested, plans were formulated for another attempt. This would be the last chance, as Endeavour had only enough propellant aboard to support one more rendezvous. The following day, the crew practised getting three pressure – suited astronauts into an airlock that was designed to accommodate just two. Other astronauts simulated the operation in the water tank at JSC and the crew played an important role in the final decision to try the first three-person EVA.

On 13 March, Thuot, Hieb and Akers ventured outside and placed themselves in foot restraints 120° apart around the payload bay. Hieb was stationed on the starboard wall of the bay and Akers stood on a borrowed strut from the ASSEM experiment, while Thuot rode the RMS. Brandenstein and Chilton flew Endeavour and gently closed in on the satellite, allowing all three EVA astronauts to reach up and grasp the satellite by the three electric motors that would deploy the satellite’s cylindrical solar panel. Over a difficult 85 minutes, the capture bar was finally attached to the satellite, allowing the RMS to manipulate it over the payload bay and onto the new kick motor. Thuot and Hieb then used hand-operated ratchets to pull the satellite down and latch it into place with four clamps. They then connected two electrical umbilicals. With the astronauts back in the airlock, but with an open hatch in case they were still required, the new PKM was ejected from the payload bay. Thirteen minutes later, a procedural error on the checklist prevented the initial deployment. The EVA set a new duration record, surpassing that of the Apollo 17 astronauts on the Moon in December 1972. The new engine worked perfectly on 14 May, placing the satellite on its way to geosynchronous orbit.

The same day, Thornton and Akers were in the payload bay performing the ASSEM EVA demonstration. Originally scheduled for two EVAs, the Intelsat difficulty had curtailed this to a single excursion. The pair assembled a pyramid out of struts to simulate a station truss section, then attached a triangular pallet to this to simulate the mass of a major component such as a propulsion module. Scheduled for three hours, the astronauts found that it took twice as long as expected and proved very tiring, forcing other activities planned for this EVA to be cancelled. The mission had been extended by two days to complete its primary objectives and this took a toll on the crew. They also had to complete the rest of their experiment programme, including the Commercial Proton Crystal Growth experiment, the UV Plume Instrument experiment and the USAF Maui Optical Site experiment. Post-flight inspections revealed negligible damage and the crew and flight controllers reported only minor problems. The new vehicle had joined the fleet in style.

Milestones

150th manned space flight 77th US manned space flight 47th Shuttle mission 1st flight of Endeavour

25th US and 46th flight with EVA operations 1st Shuttle mission to feature four EVAs 1st use of landing drag parachute 1st three-person EVA

1st astronaut attachment of rocket motor to orbiting satellite

STS-60 |

|

Int. Designation |

1994-006A |

|

Launched |

3 February 1994 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

11 February 1994 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET-61/SRB BI-062/SSME #1 2012; #2 2034; #3 2032 |

|

Duration |

8 days 7 hrs 9 min 22 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

Wake Shield Facility 1 operations; SpaceHab 2; first flight of a Russian cosmonaut on a US mission |

Flight Crew

BOLDEN Jr., Charles Frank, 47, USMC, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 61-C (1986); STS-31 (1990); STS-45 (1992) REIGHTLER Jr., Kenneth Stanley, 42, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-48 (1991)

DAVIS, Nancy Jan, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-47 (1991)

SEGA, Ronald Michael, 41, civilian, mission specialist 2

CHANG-DIAZ, Franklin Ramon, 43, civilian, mission specialist 3, 4th mission

Previous missions: STS 61-C (1986); STS-34 (1989); STS-46 (1992)

KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstaninovich, 35, civilian, Russian mission specialist 4, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM7 (1988); Soyuz TM12 (1991)

Flight Log

As part of the agreement between the US and Russia on manned space flight operations, the first Russian cosmonauts (Mir veterans Sergei Krikalev and Vladimir Titov) arrived at NASA JSC in Houston in late October 1992, to train for STS-60 and STS-63. Their training would be an abbreviated form of NASA mission specialist (not candidate) training, which would include RMS operations and EVA training using American EMU hardware. The training flow for the cosmonauts took into account their vast experience in the Russian programme. In February 1993, Krikalev was assigned the prime position on STS-60 with Titov as his back-up, reversing the roles for STS-63. These flights were the precursor missions that would include up to ten (later reduced to seven) long-duration American residencies on Mir, Shuttle dockings and further Russian cosmonauts incorporated into crews for Shuttle-Mir

|

Russia’s first cosmonaut to fly on the American Shuttle, Sergei Krikalev is seen on the aft flight deck of Discovery during the STS-60 mission. He uses the SAREX equipment to talk with American students in Maine and holds a camcorder for recording in-flight activities |

missions. This all fell under Phase 1 of the International Space Station programme, the sixteen-nation cooperative programme that essentially replaced both the US Space Station Freedom and Russian Mir 2 programmes.

The mission of STS-60 had been postponed from November 1993 and rescheduled for January 1994, but a leaking aft RCS thruster in the orbiter forced a further delay while it was investigated. On the third attempt, the launch occurred without incident and the SpaceHab experiments were activated shortly after reaching orbit. The twelve experiments in the programme included four in materials sciences, seven in life sciences and a space dust collection experiment. On the third flight day, the crew attempted to deploy the Wake Shield Facility, but radio interference and problems in reading status information from the facility meant that the attempt had to be abandoned. The following day, the deployment was again cancelled when the facility’s attitude control system developed problems. For two days, the facility remained on the end of the robot arm, conducting abbreviated experiments and being berthed during FD 6. The Wake Shield Facility was planned as a deployable and retrievable experiment platform that would leave a vacuum wake in low-Earth orbit, which was calculated as being 10,000 times greater than that created on Earth in the laboratory. Within this “ultra-vacuum” environment, it was planned to grow defect-free thin film layers of semi-conductor materials (such as gallium arsenide).

Two experiments deployable from GAS canisters (six orbital debris calibration spheres – ranging from 5 to 15 cm in diameter, and a German satellite that measured acceleration forces) were carried on the flight, as well as three other GAS canister experiments. There was also a capillary pump experiment and an auroral photography experiment included in the science package. Krikalev had been given crew roles in photography and TV tasks, as well as maintenance activities during the flight. He supported SpaceHab systems and RMS operations and participated in the Earth observation programme. He was also assigned roles in some of the secondary experiments on the mission. His primary role was participation in the joint in-flight medical and radiological investigations. Krikalev also used the SAREX ham radio equipment to talk with operators in Moscow. After a one-orbit waive-off due to unfavourable weather at KSC, the mission ended with a perfect landing, a successful opening of the series of cooperative missions that would lead to the ISS programme.

The most significant achievement was that a cosmonaut could be trained to work with an American crew on an American mission in such a short time. This was a strong reflection of the capabilities of Krikalev, who took to both the English language and the American training system more easily than Titov. It was also a compliment to the vast experience both men brought from their own programme. Krikalev had more than 400 days experience from two missions and Titov had logged a year in space on one mission. The Russians seemed to integrate well with the American programme, but the question now was whether the Americans could do the same when they had to spend far longer in Russia training for a residency on Mir.

Milestones

167th manned space flight 90th US manned space flight 60th Shuttle mission 18th flight of Discovery 1st Russian cosmonaut on Shuttle

1st cosmonaut not to be launched from Baikonur or land in Russian territory 1st flight of Wake Shield Facility 100th Get Away Special (GAS) payload

April 2002

April 2002