‘STAR SAILORS’

A little more than a year earlier, Gagarin had been just one of hundreds of Soviet military pilots who received unusual instructions to undergo classified briefings and physical and psychological tests as part of an entirely new, and mysterious, aviation project. The search for the world’s first spacefarers began in earnest in May 1959, when representatives of the armed forces, the scientific community and the design bureaux met at the Soviet Academy of Sciences under the supervision of VicePresident Mstislav Keldysh to discuss methods of selecting the most suitable candidates for Earth-orbital missions. Aviators, rocketeers and even car racers were considered in the early days, but, at length, bowing to Soviet Air Force pressure, Keldysh agreed to narrow the selection criteria to qualified pilots from this branch of the military.

Despite its obvious vested interest in wanting to have ‘its’ fliers taking the first manned spacecraft beyond the atmosphere, the logic was inescapable: Soviet Air Force pilots had proven themselves under exposure to hypoxia, high pressures and varying G loads and had undergone rigorous ejection-seat and parachute training. In addition to their flying experience, candidates would only be admissible if they could meet the height and weight requirements of the Vostok spacecraft: they needed to be no taller than 1.75 m and weigh no more than 72 kg. Moreover, anticipating that they would be embarking on lengthy careers as ‘cosmonauts’ (the word literally means ‘star sailor’), the age limit was set between 25-30 years old.

Throughout 1959, groups of physicians were sent to a number of air bases in the western Soviet Union and by August the selection teams had the records of more than 3,000 pilots ready for inspection. Most of these were eliminated at a fairly early stage, on the basis of not meeting the height, weight, age or medical criteria; some, indeed, were dropped for bronchitis, angina, gastritis and colitis, renal and heptic colic and pathological cardiac shifts. The remainder were then systematically interviewed from early September, still unaware of exactly what the so-called ‘special flights’ project entailed. Three thousand soon became a little over two hundred, who were despatched in groups of about 20 for further tests at the Central Scientific Research Aviation Hospital in Moscow. In addition to more interviews, the candidates were spun in stationary seats to assess their vestibular apparatus, placed in low-pressure barometric chambers and wrung through a centrifuge to evaluate their performance under high-gravity loads. Original plans, it seemed, called for seven or eight pilots, but Sergei Korolev insisted on tripling this number, for no other reason than because he wanted a larger team than the United States’ seven – strong Mercury group.

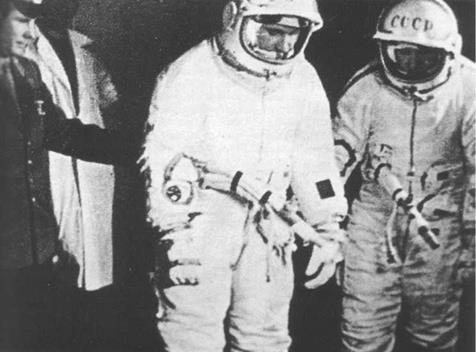

In January I960, Konstantin Vershinin, commander-in-chief of the Soviet Air Force, formally signed plans to establish a centre for cosmonaut training in Moscow. Although it was under the control of physicians, the Air Force General Staff eventually assumed command of cosmonaut affairs, under Nikolai Kamanin. It was Kamanin who formally approved a final shortlist of 20 Air Force cosmonaut candidates in late February: Ivan Anikeyev, Pavel Belyayev, Valentin Bondarenko, Valeri Bykovsky, Valentin Filatyev, Yuri Gagarin, Viktor Gorbatko, Anatoli

Kartashov, Yevgeni Khrunov, Vladimir Komarov, Alexei Leonov, Grigori Nelyubov, Andrian Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, Mars Rafikov, Georgi Shonin, Gherman Titov, Valentin Varlamov, Boris Volynov and Dmitri Zaikin. Their ages ran from just 23 in Bondarenko’s case to as old as 34 in that of Belyayev; this criteria was waived in a couple of instances out of respect for their exemplary performance during testing. Some of them would become the most famous names in spaceflight history, whilst others would disappear into anonymity. . . and, in a few cases, disgrace.

On 7 March, the 20 cosmonauts were given their welcoming speech by Vershinin at the Central Scientific Research Aviation Hospital. A week later, after settling their affairs at their respective air bases, they began training with Vladimir Yazdovsky’s first class in aerospace medicine. The following four months were consumed by a mixture of in-depth lectures and an intense physical fitness regime, the latter of which included two hours daily of intensive calisthenics at the Central Army Stadium in Moscow. Parachute training was also conducted in the Saratov region, near Engels, using a converted An-2 aircraft and within six weeks each of the candidates had made between 40-50 jumps over water and land, from high and low altitudes and during daytime and nighttime.

It was partway through this training regime that the Air Force began exploring a number of more suitable sites for the cosmonauts to continue their preparations. Two possible places were identified: one in Balashikha and the other close to the Tsiolkovsky Railway Station in Shelkovo. The latter was eventually chosen in recognition of its isolated location, large area and proximity to Korolev’s OKB-1 design bureau, the Academy of Sciences and the Monino airfield. The new cosmonauts and their training staff relocated to the new site at the end of June I960 and the suburb itself, near Shchyolkovo, some 30 km north-east of Moscow, came to be known as Zelenyy (‘Green’). Nowadays, it has become world-famous as ‘Zvezdny Gorodok’ (variously ‘Star City’ or ‘Starry Township’).

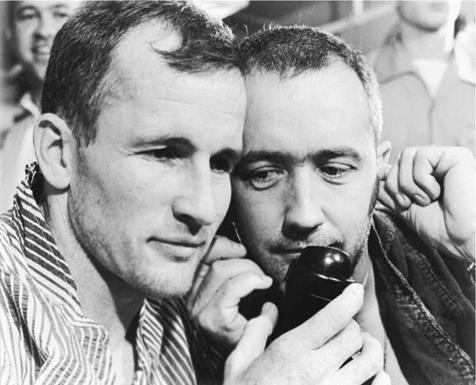

With the appearance of the new cosmonaut town came the development of the first spacecraft simulators in which they could work. Known as ‘TDK-1’ and built by the M. M. Gromov Flight Research Institute, it received its first trainees – Gagarin, Kartashov, Nikolayev, Popovich, Titov and Varlamov, nicknamed ‘The Vanguard Six’ – in the summer of 1960. The make-up of this group changed almost immediately, however, when a reddening was discovered on Kartashov’s spine, diagnosed as haemorrhages and he was dropped from the Six. He was eventually dismissed from the cosmonaut team in April 1962. Shortly after Kartashov’s removal, Varlamov was involved in a swimming accident in which he displaced a cervical vertibra and disqualified himself from consideration. Their places were taken by Bykovsky and Nelyubov. The ‘new’ Six formed a cadre who would vie for the chance to become the Soviet Union’s first man in space. Indeed, with the exception of Nelyubov, they would fly five of the six Vostok missions. First among them, of course, was Yuri Gagarin, whom many cosmonauts felt had been a strong contender right from the first time he met Korolev. His journey to the stars had begun, rather strangely, as a child saboteur.

FARMBOY

After checking his safety, the boy crept over to a pile of Panzer batteries and began dropping fistfuls of soil into their accumulator caps. On other occasions, he might deliberately muddle up their chemicals, pouring them into the wrong compartments, so that SS commanders would return furiously to Klushino at nightfall to complain about their tanks’ dead batteries. Sometimes, he would even shove potatoes deep inside the exhaust pipes of German military cars. It was the autumn of 1942. The Nazi invasion had begun a year before, but, after scoring several major successes, they had now been drawn so deep into Soviet territory that the harsh Russian winter prompted a lengthy retreat. The Smolensk district, some 160 km west of Moscow and containing Klushino, lay directly in the path of the Nazi fallback. It was here that the young boy, Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin, born on 9 March 1934, saw war for the first time. Yet although his childlike attempts at sabotage certainly helped his village’s struggle against the German occupiers, he didn’t do it for patriotism. He did it to avenge himself on the Devil.

‘The Devil’ was a red-haired Bavarian known only as Albert, whose job included collecting flat batteries from German vehicles and replenishing them with acid and purified water. The Klushino children had already used broken glass to burst their tyres and, one day, in retaliation, Albert tried to murder Gagarin’s younger brother, six-year-old Boris, by stringing him from an apple tree with a woollen scarf. The attempt failed, but Albert still managed to evict the entire family from their home. Later, the two elder Gagarin children were abducted and taken to Poland, their father was beaten and their mother slashed with a scythe. It was just the start of what Gagarin’s fellow cosmonaut Alexei Leonov would later describe as ‘‘a very dark period for our country’’.

Following the expulsion of the Germans from Klushino in March 1944, the family eventually moved to nearby Gzhatsk, building a new home, and as Gagarin entered his teens he and Boris learned to read from Russian military manuals. However, it was witnessing a wartime dogfight between two Soviet Yak fighters and a pair of German Messerschmitts that kindled Gagarin’s interest in aviation, garnered a fascination with mathematics and physics and led to model aircraft clubs and maddening demands for his father to build him miniature gliders. By 1950, he had applied – but was not accepted – to study at the College of Physical Culture in Leningrad, hoping to become a gymnast or sportsman. Instead, he took his second option as an apprentice foundryman at the Lyubertsy Steel Plant in Moscow. His work record led directly to training at the newly-built technical school in Saratov on the Volga River and, while there, he saw a notice for an aeroclub, which he promptly joined.

After graduating from Saratov in 1955, and by now with considerable flying experience in an antiquated Yak-18 trainer through the aeroclub, Gagarin was recommended by his instructor for the pilots’ school in Orenburg. This required him to sign up as a Soviet Air Force cadet, which neither of his parents found particularly appealing, and one of his Orenburg instructors, Yadkar Akbulatov, considered him by no means a piloting prodigy and felt that Gagarin may have failed the school

altogether if he could not land without bouncing on his tyres. Ultimately, Akbulatov recalled later, Gagarin solved his problem by placing a cushion under his seat to gain a clearer line of sight with the runway. Never again, it is said, did he fly without the benefit of a cushion.

Whilst at Orenburg, Gagarin met his future wife, Valentina, whom he married in October 1957, only three weeks after the launch of Sputnik 1. By this time, he had begun flight training in high-performance MiG-15 jets, successfully qualified with outstanding grades from the pilot’s school and earned a lieutenant’s commission with a posting to the Nikel base at the northern tip of Murmansk. During his time at this remote place, 300 km north of the Arctic Circle, he flew MiG-15 reconnaissance missions, enduring terrible weather conditions, with ice on his control surfaces and snow blindness proving an almost daily hazard. Then, in October 1959, with his wife and two-year-old daughter desperate to leave the sub-zero setting, something happened that would change his life forever.

At first, the recruiting team that arrived at Nikel sought interviews with the pilots, in which mysterious questions were posed about flying in “more modern planes’’, then “flying something completely new’’ and later “long-distance rocket flights’’. As the pilots were winnowed into smaller groups, they were sent to the Bordenko Military Hospital in Moscow for extensive medical and psychological screening. Finally, after more than 2,000 candidates had been poked and prodded, on 8 March 1960 a cadre of 20 pilots was selected from throughout the Soviet Union to fly the first missions into space. Most were twentysomethings – the intention being that they would be hired whilst young to prepare them for careers as cosmonauts – and each was less than 170 cm tall and below 70 kg in weight to meet Vostok’s limitations.

For the remainder of 1960, the trainees undertook academic and physical work in Moscow’s major scientific establishments, including the Zhukovsky Academy of Aeronautical Sciences on Leningradsky Prospekt and the Institute of Medical and Biological Problems, near Petrovsky Park. Gagarin and the others were sealed, individually, inside isolation chambers for days at a time, with the barest of provisions, as pressure levels were alternately raised and lowered and the trainees given mind-numbing tasks to test their ability to overcome the tedium of lengthy flights. Towards the end of one 24-hour session, Gagarin even tried to alleviate his boredom by conjuring up songs about the electrodes taped to his chest. At other times, the cosmonauts were whirled in a centrifuge – sometimes peaking at 13 G – which caused their breathing to become laboured, their facial muscles to twist and contort and, said Gagarin, “the blood in my veins felt as heavy as mercury’’. Still more torture was effected through oxygen-starvation experiments, which made the more ‘normal’ pilot-training activities, such as parachute jumps, a blessed relief.

On 6 January 1961, six of the cosmonauts – Gagarin, Titov, Valeri Bykovsky, Andrian Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich and Grigori Nelyubov – were selected for final examinations prior to the announcement of who would fly first. Eleven days later, the six men were each sealed inside a Vostok simulator for almost an hour apiece to describe the equipment and operations to be conducted during each phase of a mission. Their understanding of how to orient the spacecraft for a manual retrofire and properly egress the capsule was scrutinised. Gagarin, Titov, Nikolayev and

Popovich were rated “outstanding” by the examiners, with Nelyubov and Bykovsky a close “good”. Written examinations followed, after which all six were proclaimed fit to fly, with Gagarin, Titov and Nelyubov categorised as the best candidates.

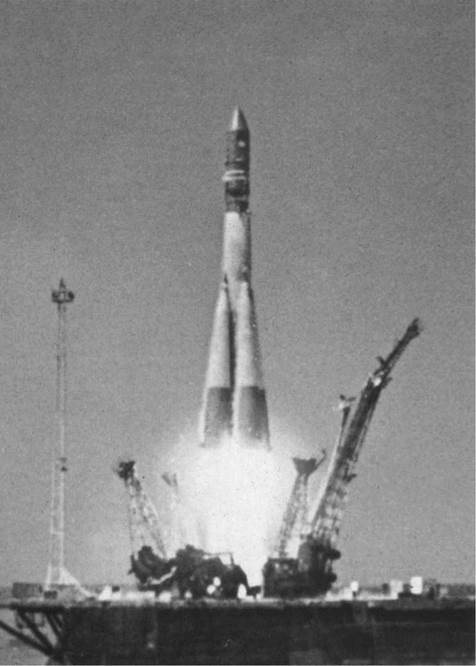

Three days before launch, Gagarin was chosen and Titov would later agree that from an image-conscious Soviet perspective, he was indeed the perfect choice. “Look at his biography,” Titov recalled years later. “Yuri Gagarin is an ordinary man from Smolensk. During the war, his brother and sister were driven away. After graduating, he went to a factory school and became a foundry worker, then followed the Saratov industrial specialised school, an air club and a flight school. He was a lad who made his dream come true all by himself, without a father and mother to help him.” In fact, on 12 April 1961, as Gagarin waited atop Korolev’s latest Little Seven, ready for his chance to make history, his parents, brothers and sister had absolutely no knowledge of what he was about to do. By nightfall, Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin would be the most famous man on the planet.