Well-Earned Fame

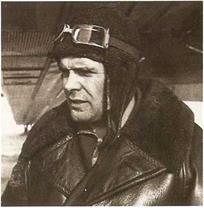

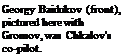

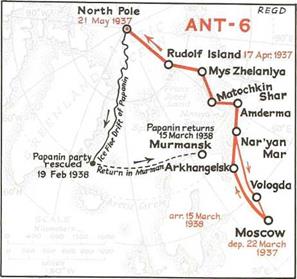

After the various great flights made by Soviet aircraft, the pilots and crew were lavishly decorated, receiving many medals and testimonials in the Soviet tradition. Moscow witnessed receptions that were as impressive, if not quite so lavish, as those bestowed in New York on Lindbergh, Earhart, or Hughes. And they were well earned. Mikhail Vodopyanov, for example, had built up hundreds of hours of flying in remote parts of Russia, including the opening of the Dobrolet route to Sakhalin (page 24). He had pioneered the route to Rudolf Island, and had campaigned for aircraft landings on the North Polar ice, in opposition to other views that the Papanin party should be dropped by parachute. His crew members Mikhail Babushkin and Ivan Spirin had both flown big airplanes as early as 1921, in the Il’ya Murometsy, no less. Vasily Molokov had been one of the heroes of the Chelyuskin rescue, and his radio operator had been with him on the long Siberian circuit (page 27). Anatoly Alexeyev had flown on a relief party to the Severnaya Zemlya islands in 1934; while Ilya Mazuruk and Pavel Golovin already had outstanding records. When the Soviet Union decided to Go For The Pole, it had the best cadre of trained and experienced pilots in the world to face the daunting challenge.

_______ FLIGHT TO THE NORTH POLE, 1937_____

Director of Operations Dr Otto Shmidt

Deputy Director of Operations Mark Shevelev Meteorologist at Rudolf Island Boris Dzerdzeyevsky

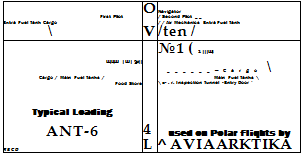

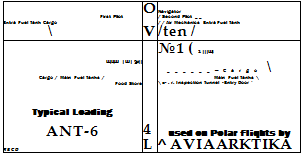

ANT-6 N-170 Total on board

(inc. Papanin party, below), 11

Pilot, M. V. Vodopyanov • Co-pilot, M. S. Babushkin • Navigator, I. T.Spirin Radio Op., S. A. Ivanov • Air Mechanics, F. Bassein, Morozov, Petenin

ANT-6 N-171 Total on board, 11

Pilot, V. S. Molokov • Radio Operator, Stromilov • Navigator, Ritsland ANT-6 N-172 Total on board, 11

Pilot, A. D.Alexeyev • Navigator, Zhukov, Moshkovsky ANT-6 N-169 Total on board, 5

Pilot, i. p. Mazuruk • Rozlov, Akkuratov ANT-7 N-166 Crew only, scout aircraft)

Pilot, P. c. Golovin • Navigator, Volkov, Terentyev

• Mechanics, Shekurov, Timofeyev

Polar Party (with N-170) Remained at the North Pole

Leader, I. D. Papanin • Navigator, Y. K. Fedorov

• Radio Operator, E. T. Krenkel, P. P. Shirshov

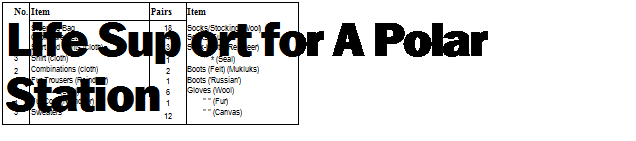

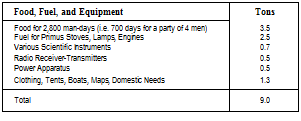

Total weight of supplies carried to the North Pole 9 tons

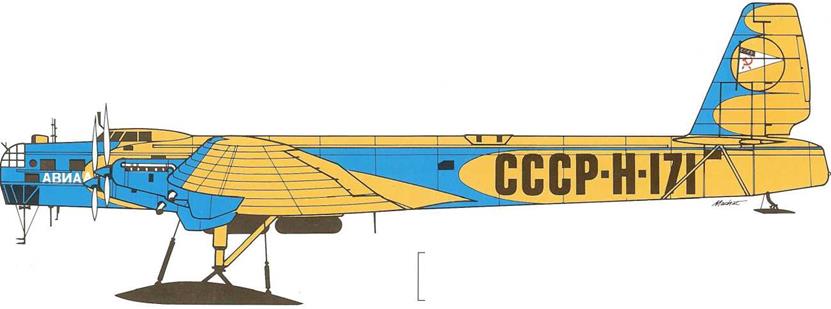

Weight Watchers

Weight Watchers

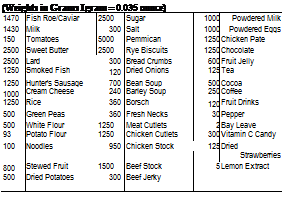

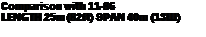

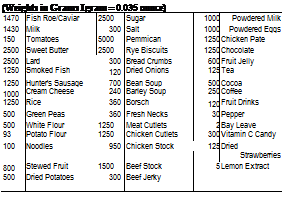

To equip the Papanin Expedition, every ingenious precaution was taken to avoid superfluous weight. Tents were of light-weight silk and aluminum. Utensils were of plastics or aluminum. The aircraft ladders were convertible into sleds. Special equipment such as the sounding line and the bathymeter were re-designed to save weight. Both the aircraft crews and the members of the expedition were eternally grateful for the innumerable contributions made by the ‘backroom boys’ in Leningrad, Moscow, and other sources of equipment supply.

Mow Much Extra

To carry even this finely tuned total weight of nine tons, divided between the four ANT-6 load-carrying aircraft, extra fuel also had to be taken, in addition to the provisions listed in the tables on this page. Almost two tons extra had to be carried by each aircraft. But the dome-shaped airfield on the plateau at Rudolf Island offered shallow slopes, down which the departing aircraft could gain speed and lift; and every item of nonessential equipment was stripped from the interior, and every non-essential item of personal effects was left behind.

lest Bombing

Landing a 24-ton aircraft on an ice-floe, no matter how big, was a speculative proposition. It was determined that the minimum ice thickness required was 70cm (2ft); engineers then devised a 9.5kg (211b) ‘bomb’. It was shaped like a pear and fastened at its rear or trailing end was a 6-8m (20ft) line with flags attached. If the ice was less than 70cm, the ‘bomb’ went straight through. If more, it stuck, and the flags, draped on the ice, indicated that landing was possible. This method was first utilized on the Papanin expedition.

PAPANIN EXPEDITION

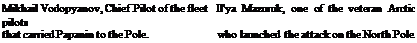

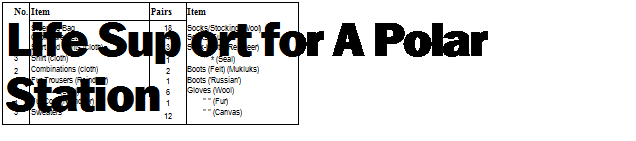

CLOTHES/PERSONAL ITEMS PER TEAM MEMBER

Their Tiny Hands Were Frozen

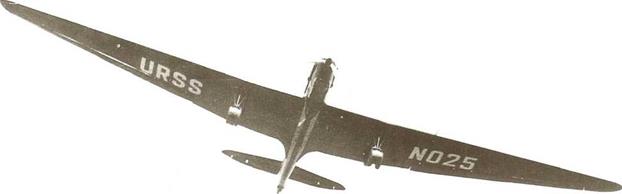

During the final flight from Rudolf Island to the North Pole, Mikhail Vodopyanov realized that one of the ANT-6’s engines was leaking water from its radiator, with its precious anti-freeze liquid disappearing into thin air. Vodopyanov’s trusted chief air mechanic, Flegont Bassein, together with co-mechanics Morozov and Petenin, crawled along the tunnel in the wing (see opposite and diagram below) and tried to stop the flow. They came up with an ingenious solution, by placing cloths over the leak, soaking up the outflow, squeezing them out into a container, and pouring the liquid back into the radiator. The engine kept going.

The mechanics did too, but barely. To reach the leak, they had had to force an opening in the leading edge of the wing, radiators obviously being exposed to the airflow. It was an act of fortitude that nearly cost them their hands.

PAPANIN EXPEDITION

TOTAL FUEL, FOOD, AND EQUIPMENT

FOOD TAKEN ON PAPANIN EXPEDITION

Two ANT-6s of Aviaarktlka (SSSR-N211 and N212), wanning up to go to search for Levanevsky in October 1937.

|

An ANT-7 in a typical Arctic scene, (all photos: Boris Vdovienko)

|

|

|

A special feature in the design was a tunnel that permitted air mechanics to crawl along the whole length of the wing, to inspect fuel tanks and cargo holds; and on one notable occasion (see opposite page) this was used to perform some unusual maintenance on one of the engines.

|

|

AM-34RN (4 x 970hp) ■ MTOW 22,600kg (49,8201b) ■ Normal Range 1,350km (840mi)

A Great Airplane

Bill Gunston, renowned technical aviation authority and compiler of encyclopedic volumes about aircraft, including a masterpiece on Soviet types, says this about the Tupolev-designed ANT-6, also known as the TB-3 or the G-2: "This heavy bomber was the first Soviet aircraft to be ahead of the rest of the world, and one of the greatest achievements in aviation history" and that, "the design was sensibly planned to meet operational requirement and was highly competitive aerodynamically, structurally, and in detail engineering." This was in 1930.

A Big Airplane — and Plenty of Them

Give or take a ton or two, depending on the version, the ANT-6 weighed, fully equipped for take-off, about 22 tons. Most G-2s weighed 22,050kg (48,5001b). By comparison, the contemporary German Junkers-G 38 weighed 24 tons, but only two were built, compared with no less

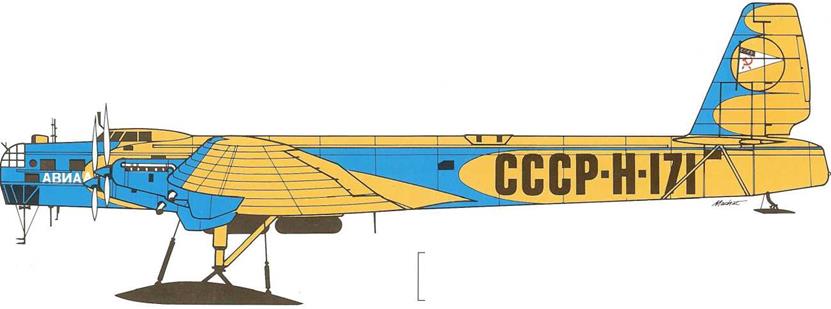

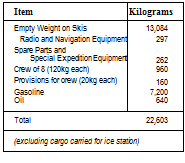

A rear view of ANT-6 SSSR-N-170 in which Vodopyanov took Papanin to the North Pole. This picture well illustrates the excellent basic 1930 design of the world’s first heavy transport that went into series production, (photo: Boris Vdovienko)

than 818 ANT-6s. Of these, the vast majority were for the Soviet Air Force, painted dark green, with sky blue undersides; about ten or twelve ANT-6s were allocated to Mark Shevelev’s Polar Aviation (Aviaarktika), and painted in the orange-red and blue colors. The four special versions prepared for the Papanin expedition, according to Tupolev historians, were in bare metal, probably to save precious weight. The British and French industries had nothing in the same league, and the U. S.A. had not yet thought of the B-17.

A Versatile Airplane Too

Designed primarily as a bomber, the type was adapted for other purposes. Design started way back in May 1926, wind tunnel testing was completed in March 1929, and Mikhail Gromov made the first test flight on 22 December 1930. Throughout its lifespan (production ceased early in 1937) it underwent many improvements, culminating in the ANT – 6A, specially modified for Dr Otto Schmidt’s Aviaarktika’s assault on the North Pole; and it was also used during the 1930s by Aeroflot, reportedly carrying as many as 20 passengers.

He Meeting

On 3 August 1935, the latest product of the TsAGI design organization, the ANT-25, designed by Andrei Tupolev, was on a proving flight over the Barents Sea, north of Murmansk. The crew consisted of Sigismund Levanevskiy, then considered to be the Soviet Union’s leading pilot, Georgy F. Baidukov, and Victor Levchenko. The aircraft had fuel system problems and, nearing the point of no return, Lavanevskiy turned back, landing near Novgorod, instead of the Moscow base.

In mid-September, a meeting was held in Josef Stalin’s office in the Kremlin. It was attended by the three crew members, faced across the table by Molotov, Voroshilov, and Andrei Tupolev. At the head of the table, Stalin conducted an enquiry, aided by his pipe, whose smoke drifted over the room. He asked Levanevskiy about his plans, whereupon the pilot said he did not trust the ANT-25, and Tupolev left the room in disgust. Stalin suggested that, for the next flight into the Arctic, American assistance should be sought; but Baidukov felt that the aircraft’s problem could be rectified. Answering Levanevskiy’s allegation that a single-engined aircraft (the ANT-25) had a 100 percent chance of disaster if an engine failed, Chkalov responded with the remark “With four engines, you have a 400 percent chance!" He won the day.

He Flight to Udd

Although Stalin had originally wished to make a prestige-seeking flight across the Pole to the U. S.A., he decided, early in 1936, that, for political reasons, a flight to the U. S.S. R.’s Far East would be preferable. Later, he was reported to have said that the successful flight had been “worth two armies." By this time, Baidukov had begun to work with Valery P. Chkalov, a pilot with a reputation for taking risks, but a master of his trade. The ANT-25’s fuel problems were corrected.

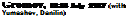

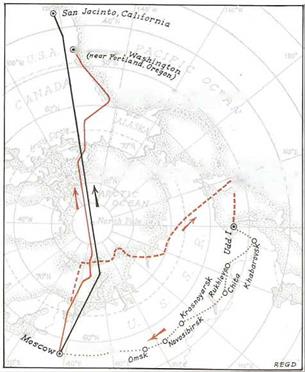

On 20 July 1936, Chkalov, Baidukov, and navigator Aleksander V. Belyakov flew the aircraft from Moscow, by a route that took them first due north from Moscow and then by a near-Great Circle course over eastern Siberia, aiming for Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, which, however, was blanketed by impenetrable weather. Turning west, they made landfall across the Sea of Okhotsk, on the tiny island of Udd, near the mouth of the Amur River. On this island, now renamed Chkalov (along with neighboring islands Baidukov and Belyakov), a dignified

monument commemorates this notable flight of 9,374km (5,825mi) in 56hr 20min. The ANT-25 had made its case.

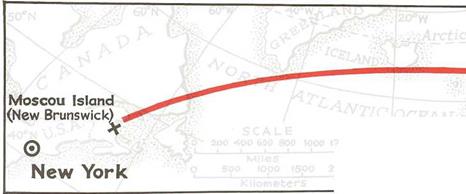

The First Trans-Polar Flight

The following year, from 18 to 20 June 1937, they made the historic flight that ranks as one of the greatest trail-blazing conquests of the air, and one of the most dramatic. Flying at first due north to the Pole and then continuing due south, they made their way to Portland, Oregon, landing, however, at the military Pearson Field at Vancouver, Washington State. The ANT-25 had covered a distance of about 10,000km (6,200mi), officially recorded as a Great Circle distance of 8,504km (5,285mi) in 63hr 25min. The flight captured the imagination of the whole world and Chkalov was hailed as the Russian Lindbergh.

Tie Second Trans-Polar Flight

As if to trump Chkalov’s ace — and perhaps to remind everyone in the U. S.S. R. that he was once the premier Soviet pilot — Mikhail Gromov, with Andrei B. Yumashyev and Sergei A. Danilin, made a second trans-Polar flight only a month after Chkalov. On 12-14 July, also in an ANT-25, with its bright red wings making a dramatic impact, this crew flew from Moscow to a grass meadow near San Jacinto, in southern California. This time the Great Circle distance of 10,148km (6,306mi), flown in an even shorter time (62hr 17min) than Chkalov’s, because of more favorable winds and conditions, beat the world’s distance record held by the Frenchmen Codos and Rossi.

Tragic Postscript

One month later still, it was Levanevskiy’s turn. Convinced that a multi-engined aircraft was the best suited for long-distance flying (and who could argue this point today?) he set off from Moscow on 12 August 1937, in a DB-A (URSS-N209). Designed by Viktor Bolkovitinov, this was a mid-winged and much-developed version of the veteran but well-trusted ANT – 6, the very same type that so successfully had made the flights to the North Pole earlier in the year (see page 30). Levanevskiy had a crew of five: Nikolai Kasteneyev (co-pilot), Viktor Levchenko (navigator), Grigory Pobezhimov (mechanic), Nikolai Godovikov (mechanic), and Nikolai Galkovsky (radio operator). After 17hr 35min, the radio station at Cape Schmidt, in the far northeast of Siberia, heard a brief message, reporting severe trouble. The DBA and its crew were never heard of again, although repeated searches have been made.

![]()

![]()

Weight Watchers

Weight Watchers

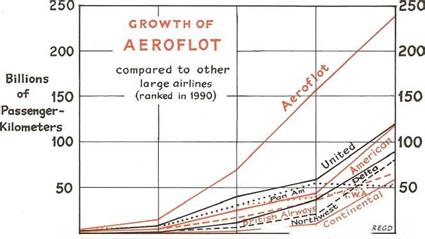

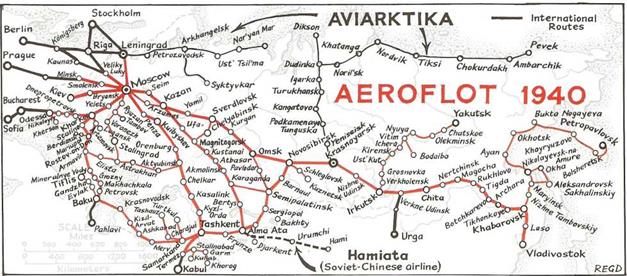

By 1940, the unduplicated mileage of Aeroflot’s route system was close to 100,000, and in that year it carried 350,000 passengers. The productivity, measured in passenger-miles flown, was 160 million. Aeroflot was now bigger than Deutsche Lufthansa, Europe’s biggest, and it was now the third biggest airline in the world.

By 1940, the unduplicated mileage of Aeroflot’s route system was close to 100,000, and in that year it carried 350,000 passengers. The productivity, measured in passenger-miles flown, was 160 million. Aeroflot was now bigger than Deutsche Lufthansa, Europe’s biggest, and it was now the third biggest airline in the world.