. Piston-Engined Twilight

|

|

|

|

Shvetsov ASh-82T (2 x 1.900hp) ■ MTOW 17,500kg (38,5801b) ■ Normal Range 1,500km (930mi)

|

|

|

|

Shvetsov ASh-82T (2 x 1.900hp) ■ MTOW 17,500kg (38,5801b) ■ Normal Range 1,500km (930mi)

164 SEATS ■ 900km/h (580mph)

Kuznetzov NK-8-2 (3 x 9,500kg,20,9501b) ■ MTOW 90,000kg (198,4151b) ■ Normal Range 2,850km (l,770mi)

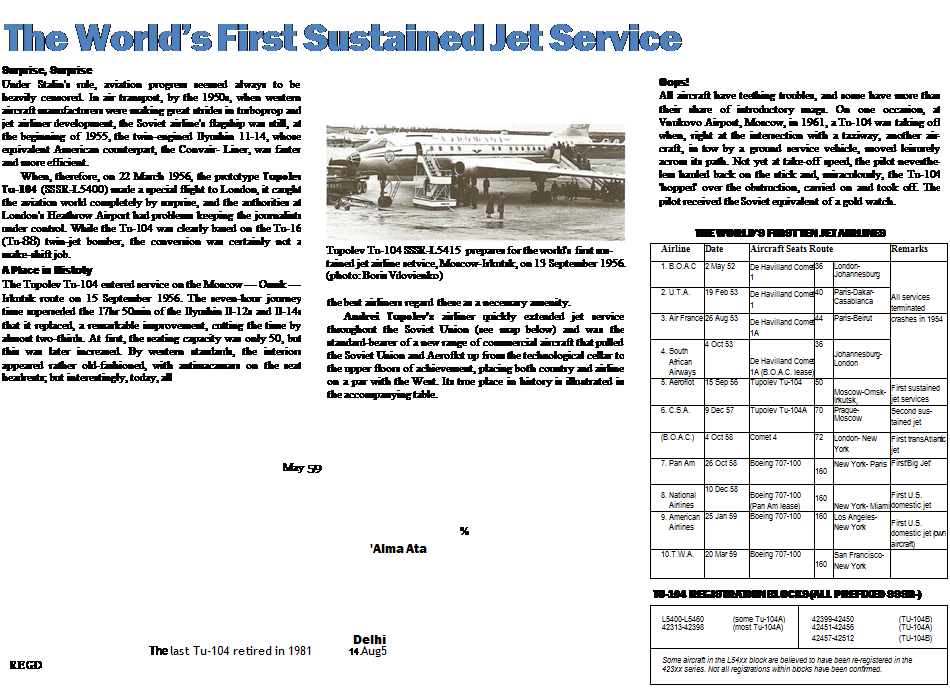

Unlikely Champion

For those interested in records, in terms of the greatest, the fastest, or the ‘mostest’, the Tupolev Tu-154 offers a fascinating exercise in statistics. The work output of the Aeroflot fleet of this type is arguably the most productive of any individual aircraft type by any individual airline in the world, measured by the standard method of calculation, based on the annual aggregate output of passenger miles.

This is not to suggest that the Tu-154 is therefore the most economical aircraft of any of its contemporary rivals. But in producing the aircraft and in operating it under the Soviet conditions of financial and operating criteria, the Tupolev Design Bureau and Aeroflot have served their country well. For offsetting the higher seat-mile costs is the excellent performance which includes the ability to take off and land at almost any reasonable airport, even those without paved runways.

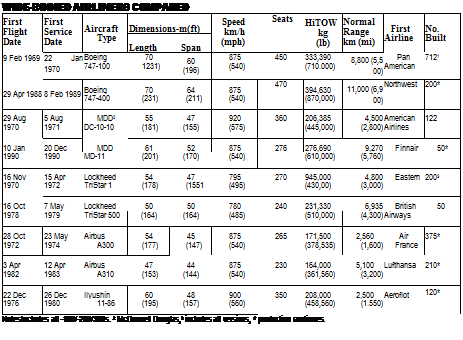

THE TRIJETS COMPARED

|

First Flight Date |

First Service Date |

Aircraft Type |

Dimensions-m(ft) |

Speed km/h (mph) |

Seats |

MTOW kg (lb) |

Normal Range km (mi) |

First Airline |

No. Built |

|

|

Length |

Span |

|||||||||

|

9 Jan |

11 Mar |

DH |

35 |

29 |

930 |

84 |

59,000 |

1,900 |

B. E.A. |

117 |

|

1962 |

1964 |

Trident |

(115) |

(95) |

(580) |

(130,000) |

(1,200) |

|||

|

9 Feb |

1 Feb |

Boeing |

40 |

33 |

930 |

94 |

76,650 |

3,200 |

Eastern |

572 |

|

1963 |

1964 |

727-1 GO |

(133) |

(108) |

(580) |

(169,000) |

(2,000) |

|||

|

27 Jul |

14 Dec |

Boeing |

47 |

33 |

970 |

140 |

94,300 |

2,400 |

Northeast |

1,260 |

|

1967 |

1967 |

727-200 |

(153) |

(108) |

(605) |

(208,000) |

(1,500) |

|||

|

3 Oct |

9 Feb |

Tupolev |

48 |

38 |

900 |

164 |

90,000 |

2,850 |

Aeroflot |

1,000* |

|

1968 |

1972 |

Tu-154 |

(157) |

(123) |

(580) |

(198,415) |

(1,770) |

|||

|

Notes: |

Production continues. |

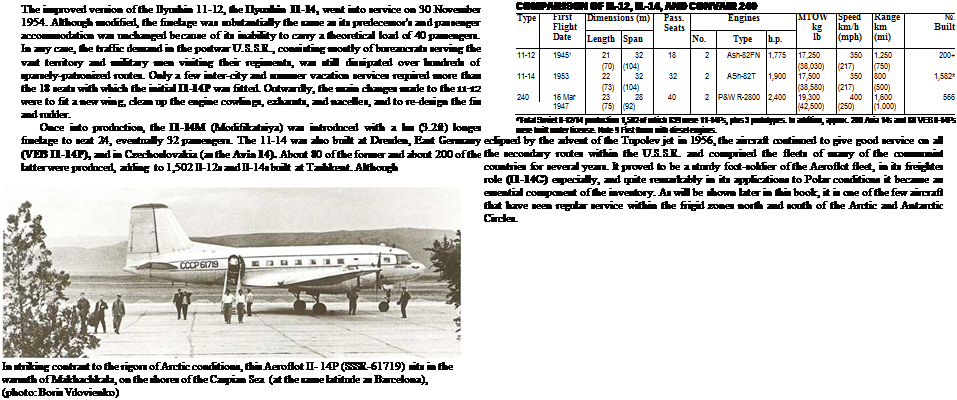

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)

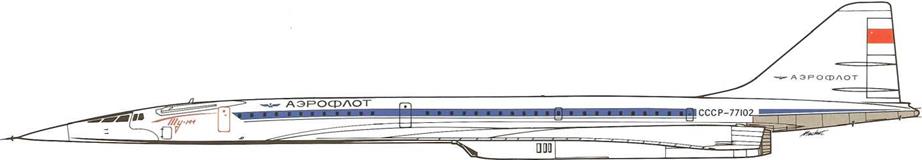

Supersonic Diversion

![]()

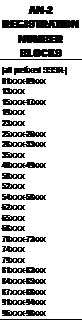

Sharing The Dream

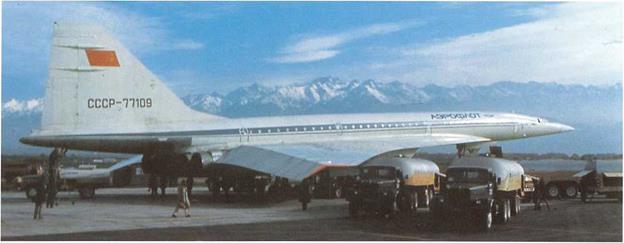

While many in the West tended to dismiss the Tupolev Tu – 144 supersonic airliner project as being a copy of the Anglo – French Concorde, with allegations of much industrial espionage worthy of James Bond himself, the two aircraft were developed and produced simultaneously. The Tu-144, as many have surmised, was not copied, and did not follow the Concorde. In fact, it was the first to fly, and it was the first to go into service, albeit for air cargo service only, almost as a series of proving flights before the passenger service.

The Tupolev Tu-144, with its extensive use of titanium structure, and its advanced aerodynamics, gained the respect of American engineers and designers as no other Soviet aircraft had ever done before. But the Soviet supersonic program gradually lost momentum as the engineers and operator (Aeroflot) came face to face with reality; and the dream of supersonic airline schedules across the length and breadth of the U. S.S. R. faded.

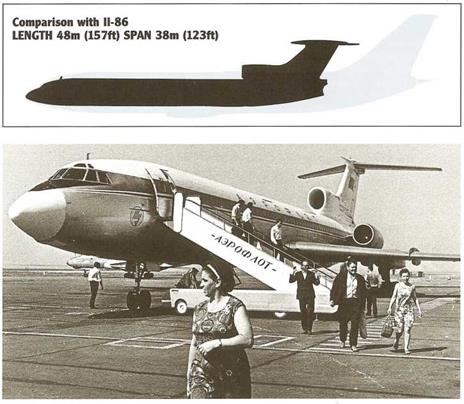

Success — and Tragedy

The Tupolev Tu-144 had its moment of glory. Test pilot E. V. Yelian made the maiden flight on 31 December 1968, a date said to have been a political imperative, to be ahead of the Concorde, which first flew two months later. Both aircraft attracted world-wide publicity but then came disaster and tragedy. At the Paris Air Show, on 3 June 1973, a Tupolev Tu – 144 disintegrated as it pulled out of a steep dive. At first thought to be structural failure, then pilot error, or a combination of both, later analysis has suggested that both pilot and aircraft could have been victims of enforced programming changes that jeopardized a well-disciplined demonstration routine. Whatever the reason, it was a shattering blow to the hopes and aspirations of the Soviet aircraft industry.

Curtailed Service Record

Nevertheless, production continued. At first wholly supportive of the SST, Bugayev, head of Aeroflot, faced formidable problems and the operation of the revolutionary aircraft

TU-144 PRODUCTION

seemed impracticable. The engines could not be programmed to operate at full efficiency in alternating subsonic and supersonic speeds; high fuel consumption inhibited long range operations; the sonic boom limited the operational scope; and the cabin noise level was unacceptably high.

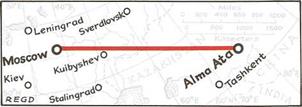

Ultimately, the entry of the Tupolev Tu-144 into airline service was almost a token gesture. Cargo flights began from Moscow to Alma Ata on 26 December 1975; passenger flights on the same route began on 1 November 1977; and these continued intermittently for only a few months before the service ended on 1 June 1978, after 102 flights. The dream had ended.

|

(Above) The Tupolev Tu-144, nose drooped, ready to take off on the inaugural passenger service from Moscow to Alma Ata on 1 November 1977. (Boris Vdovienko) |

|

|

It was left to a notable scholar of the next generation to examine the scientific principles of flight and to publish analyses of his research. Nikolai Yegorovich Zhukovskiy (1847-1921) is recognized in Russia as the founder of modern aerodynamics and hydrodynamics.

Zhukovskiy graduated at Moscow University in 1868, taught at the Moscow Higher Technical School (M. V.T. U.) from 1872, and, from 1886, simultaneously at the

University. He continued teaching in Moscow, and supervised the construction of his first wind tunnel in 1902, founded Europe’s first aerodynamic institute in 1904, and M. V.T. U.’s own aerodynamics laboratory in 1910.

His continued studies led to the publication of the law governing lift in 1906, profiles of aerofoils and propellers in 1910-11, and analyses of propeller tip vortices in 191213. He published many important monographs on aerodynamic theory.

In 1918, Nikolai Zhukovskiy was chosen to head the prestigious Central Aero-Hydrodynamics Institute (TsAGI). He died in 1921, but such was his stature that TsAGI became known as the Zhukovskiy Institute.

![]()

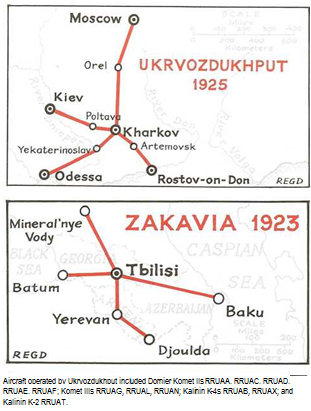

An Airline for the Ukraine

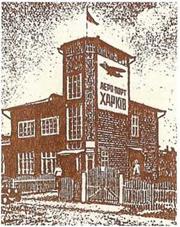

In the Ukraine, the spirit of republican independence manifested itself by the formation of an airline. On 1 June 1923, less than three months after the formation of Dobrolet, Ukrainskoe Obschestvo Vozduzhnyk Shoobshcheniy (The Ukrainian Airline Company) (abbreviated to Ukrvozdukhput) was founded. Headquarters were at Kharkov, a potential hub for air services throughout the European part of the U. S.S. R.

Dornier Establishes a Presence

Ukrvozdukhput opened for business on 15 April 1925, when it started to operate from Kharkov to Odessa and Kiev. Two months later, on 15 June, routes to Moscow and Rostov-on-Don completed a commendable spoke network centered on Kharkov. The Kalinin aircraft factory was in that city, and a cooperative arrangement was forged with the Dornier company. This latter had connections with the German Lloyd transport group which, in turn, was a partner in Deruluft. Ukrvozdukhput’s first fleet consisted of four-passenger Dornier Komet IIs, and a half a dozen six-seat Dornier Komet Ills.

Recognition of the Soviet Union (see page 15) had given Germany a doorway for trade, and effective control of the airlines provided a pathway through that door. Aside from being a strong influence on the airline operation, Dormer’s methods of construction could clearly be detected on the first Kharkov-based Kalinin aircraft, the K-l, K-2, K-3, and K-4. None went into service with Ukrvozdukhput, but were later to see service with Dobrolet.

Zakavia

A small airline was also established, on 10 May 1923, at Tiflis (Tbilisi) in Georgia. Its name

was Zakavia, derived from Zakavkazie, or Trans-Caucasus, and there were also plans to form an airline called Kakavia, but this never happened. Zakavia operated one route, to Baku, Azerbaijan, probably with a Junkers Ju 13. Late in the year, it was associated with Azerbajdzhanskogo dobro – vol’nogo vozdushnogo flota, or Azdobrolet, which existed for a few months. Beset by political upheaval, civil wars, and surrounded by high mountains, Zakavia had the odds stacked against it from the start, and after about two years of frustrated effort, it combined with Ukrvozdukhput.

|

Shvetsov ASH-621R (1 x l. OOOhp) ■ MTQW 5,500kg (12,1251b) ■ Normal Range 845km (520mi)

![]()

![]()

|

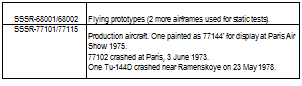

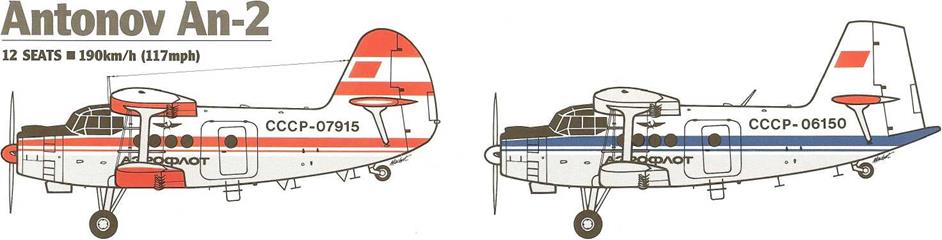

This picture encapsulates the role of the Antonov An-2 in providing the rural bus service to hundreds, perhaps thousands of small communities, such as this one in northern Kamchatka, (photo: Boris Vdovienko)

Unexplained Incident

The versatility of the An-2 ‘Annushka’ became legendary. But on one occasion, it met its match. The story goes that, at a small community far from direct authority, a pilot had to stop over at a weekend, having arrived with the mail and other contents on the Friday. The local populace, fishermen all, persuaded him to make an unscheduled flight to a local river which was reputed to be gushing fish. Fourteen good men and true piled on to the 12-seat aircraft, together with complete fishing gear, and enough provisions to last a week.

The augmented load was too much for even such a willing horse as the An-2. It managed to get off the ground, but only just. The pilot, realizing that he was not going to make it, switched off the engine, to avoid a fire, if it crash-landed. And crash-land it did, ignomi – nously, distributing pieces of aircraft around the field. The assembled company fled.

Came the dawn the next day, and the local constabulary investigated the tangled remains. Strangely, nobody in the whole community had the slightest knowledge of the incident, and the official report, in essence, decided that this was an unsolved mystery. Some dastardly vandals from foreign parts, perhaps.

60-70 SEATS ■ 2,500km/h (l,500mph)

60-70 SEATS ■ 2,500km/h (l,500mph)

Kuznetzov NK-144 (4 x 20,000kg, 44,0001b) ■ MTOW 180,000kg (397,0001b) ■ Normal Range 3,500km (2,200mi)

|

|

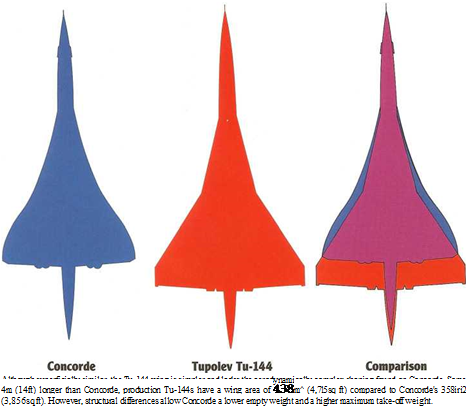

Given a specific set of performance and operational parameters, designers are usually faced with few options. Thus, at first glance, western observers tended to conclude the Tu-144 was a direct copy of the Concorde. Closer scrutiny reveals that the Tu-144 was the result of independent thinking by Andrei Tupolev’s design bureau, the most noticeable external differences to Concorde being the wing planform as shown here, and the grouping of the engines underneath the fuselage. An impressive machine by any standard, despite a lengthy gestation in three considerably diverse versions, the Tu-144 was unable to achieve sustained commercial service. However, two Tu-144s are currently in use for ozone research flights from Zhukovskiy, home of the Central Aerohydrodynamics Institute (TsAGI), near Moscow.

Given a specific set of performance and operational parameters, designers are usually faced with few options. Thus, at first glance, western observers tended to conclude the Tu-144 was a direct copy of the Concorde. Closer scrutiny reveals that the Tu-144 was the result of independent thinking by Andrei Tupolev’s design bureau, the most noticeable external differences to Concorde being the wing planform as shown here, and the grouping of the engines underneath the fuselage. An impressive machine by any standard, despite a lengthy gestation in three considerably diverse versions, the Tu-144 was unable to achieve sustained commercial service. However, two Tu-144s are currently in use for ozone research flights from Zhukovskiy, home of the Central Aerohydrodynamics Institute (TsAGI), near Moscow.

|

THE TUPOLEV TU-144 AND CONCORDE COMPARED

|

First Flight Date |

First Service Date |

Aircraft Type |

Dimensions-m(ft) |

Speed km/h (mph) |

Seats |

MTOW kg (lb) |

Normal Range km (mi) |

First Airline |

No. Built |

|

|

Length |

Span |

|||||||||

|

31 Dec |

26 Dec 19752 |

Tupolev |

65.7 |

28.8 |

2,500 |

60-70 |

180,000 |

3,500 |

Aeroflot |

174 |

|

19681 |

1 Nov 19773 |

Tu-144 |

(216) |

(95) |

(1,500) |

(397,000) |

(2,200) |

|||

|

2 Mar |

21 Jan 1976 |

ВАС-Aero- |

61.6 |

25.6 |

2,150 |

100 |

185,000 |

6,400 |

British |

205 |

|

1969 |

spatiale |

Airways |

||||||||

|

Concorde |

(202) |

(84) |

(1,350) |

(408,000) |

(4,000) |

Air France |

|

|

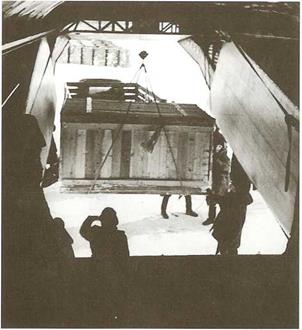

THE FIRST ANTONOV FREIGHTERS

THE FIRST ANTONOV FREIGHTERS

|

First Flight Date |

First Service Date |

Aircraft Type |

Dimensions-m(ft) |

Speed km/h (mph) |

Cargo Capacity kg (lb) |

MTOW kg (lb) |

Normal Range km (mi) |

No. Built |

|

|

Length |

Span |

||||||||

|

1958 |

18 Feb |

Antonov |

33 |

38 |

580 |

20.000 |

61,000 |

3,600 |

300? |

|

1965* |

An-12B |

(109) |

(125) |

(360) |

(44,090) |

(134,480) |

(1,940) |

||

|

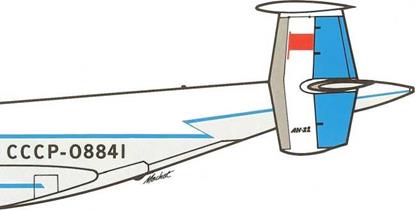

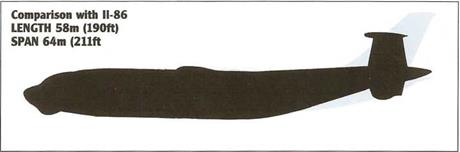

27 Feb |

1968 |

Antonov |

58 |

64 |

600 |

88,000 |

250,000 |

5,000 |

551 |

|

1965 |

An-22 |

(190) |

(211) |

(380) |

(194,00) |

(550,000) |

(3,125) |

|

Notes: * Earlier service with WS/VTA (Soviet Air Force/Transport Command) 1 Not including prototypes |

|

|

Kuznetzov NK-12MA (4 x 15,000shp) ■ MTOW 250,000kg (551,1601b) ■ Normal Range 5,000km (3,100ml)

![]()

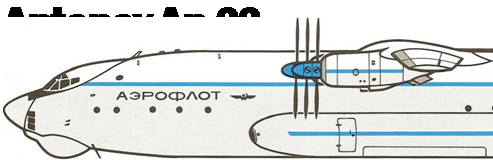

The World’s Largest

The four-engined Antonov An-22, complete with contra-rotating propellers, made it first flight on 27 February 1965, and four months later, on 15 June 1965, it made its international debut at the Paris Air Show, to the wonderment of the world. Habitually critical, sometimes disdainful, of the products of the Soviet aircraft industry, western observers were forced to take notice. Quite simply, this was a huge airplane.

It weighed 250 tons and had a payload of 100 tons. It could carry large battle tanks such as the T-62, the T-72, or the T-80, which did not complain against the customary lack of pressurization in the main cargo hold. The rear-end loading door was a neat device that not only provided the ramp, but could also form an extension to the rails along the sides of the hold, carrying the ten-ton load gantry crane. The floor was of reinforced titanium.

Following time-honored tradition, even this mammoth machine could be used on rough strips. Such extraordinary performance was made possible by an extraordinary landing gear. In each of the two fuselage fairings were three tandem wheels, for a total of twelve, to spread the load; and the tire pressure could be controlled during flight.

An Antonov An-22 prototype (SSSR-56391) on take-off. (Boris Vdovienko)

|

|

Antonov An-22 SSSR-09344 offloading relief supplies at Moscow-Sheremetyevo in April 1992. (Malcolm Nason)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

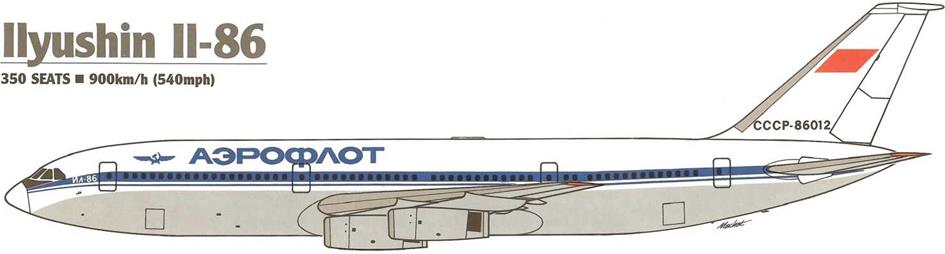

Long Gestation

By the time the Soviet Aircraft industry got under way with its first wide-bodied airliner, the Boeing 747 had already entered service. News filtered through to the West during summer 1971 that the Ilyushin Design Bureau, with Genrikh Novozhilov taking over from Sergei Ilyushin’s design leadership, was working on a four-engined wide-bodied airliner, with podded engines on the wing. The 350-seat Ilyushin 11-86 had two aisles, permitting eight – or nine-abreast seating, and like most large Soviet aircraft, had a multiple-wheeled landing gear, 14 altogether, with main wheels mounted on three tandem-mounted pairs of four. The center one of the three was mounted in the fuselage, like the long-range Douglas DC-10’s. This was — again following Soviet design custom — intended to provide soft-field, but not necessarily short-field performance. When delivered, the 11-86 normally needed about 2,500m (8,000ft) of paved runway for airline service.

Five years elapsed before the first flight, on 22 December 1976, at Khodinka, only a few kilometers from Red Square. This was almost like a new big jet making its maiden flight

from London’s Hyde Park or New York’s Central Park — or even down Washington’s Mall. Production was at Voronezh.

The first Aeroflot scheduled Ilyushin 11-86 service was in December 1980, from Moscow to Alma Ata, capital of Kazakhstan, and the destination city of the only Soviet supersonic airline service. Right from the start, the aircraft had never been promoted as a long-range airliner and it was compared unfavorably with western wide-bodied types. But with state-supplied fuel and with no competitive pressure, this was not an issue for Aeroflot’s operational requirements.

Virtue Out of Necessity

As time went on, with most of Aeroflot’s transatlantic flights of necessity stopping at Shannon, the spirit of free enterprise and innovative minds generated opportunities for cooperation between Aer Rianta, the Irish airport authority, and Aeroflot, to their mutual advantage. Aeroflot set up its own fuel ‘farm’ and thus avoided having to pay out scarce hard currency. Aeroflot paid for airport charges with fuel, which

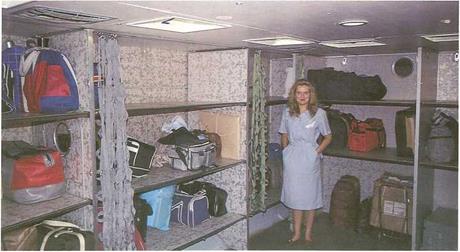

The 11-86’s carry-on baggage arrangements are excellent. Passengers can deposit their ‘not wanted on voyage’ items on the ‘left-luggage’ shelves.

Shannon then sold to other carriers, including, ironically, U. S. military VIP flights. Soviet travelers also liked the duty-free shopping amenities, and Aeroflot and the airport authorities in Russia invited the Irish to set up similar facilities in Moscow and Leningrad. Ilyushin Il-86s began to call at Shannon in the mid-1980s and Aeroflot became the airport’s biggest customer. In 1990, the Soviet airline began to take advantage of liberal international regulations as the airline world deregulated, and began to promote Ireland as a destination from the United States. Far from being a necessary evil, Shannon has become an Aeroflot asset.

|

|

|

ILYUSHIN IL-86 CARRY-ON BAGGAGE CONVENIENCE |

|

Standard Overhead Racks |

|

Lower Level Luggage Compartment |

|

|||

|

|

||

Made For The Market

The 11-86 had some good features, apart from substantially improved cabin and galley furnishings — even the seats were more comfortable than those that had served Aeroflot since time immemorial. The passenger entrance was through doors in the fuselage lower level up self-contained collapsible steps. Immediately on entering, passengers could take advantage of one of the airliner’s best features, and one that other manufacturers could well copy. This was a downstairs luggage compartment, where all excess carry-on baggage — and Russians always travel with excess — could be deposited, in a ‘not-needed-on-voyage’ aerial equivalent of shipping practice. Incidentally, anticipating extremes of temperature at such destinations as Yakutsk, plastic wing covers were made for the 11-86.

The critics of the Soviet aircraft industry concentrated on its wide-bodied candidate’s lack of range. It could not carry a full payload across the Atlantic, unless it stopped at Shannon and Gander — a necessity that had been dispensed with as long ago as 1957, with the introduction of the Bristol Britannia and the Douglas DC-7C. The critics should have put themselves in the shoes of the Ilyushin market researcher. Not a single intercontinental long-range route required the services of an airliner bigger than the Ilyushin I1-62M. The density of traffic on routes such as Moscow-New York, or Moscow-Tokyo did not come close to that on routes such as London – New York or Los Angeles-Tokyo, and could certainly not justify a 350-seat airliner. And Ilyushin had no illusions about the slim chances of breaking into the world market against Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, Lockheed, and Airbus.

Domestically, the requirement was quite different. Only two major cities in the far east, Khabarovsk and Vladivostok, were far enough away from the big cities of European Russian and Ukraine to demand an aircraft larger than the I1-62M. The main markets from Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev were to the Black Sea and Caucasian resorts, and to destinations such as Novosibirsk, Tashkent, and Krasnoyarsk — within 11-86 range. Whatever the shortcomings of the Ilyushin wide-bodied airliner for long ranges, it was just right for Aeroflot.

One of the best features of the 11-86 is the lower level baggage compartment, where passengers can stow carry-on items that are not needed during the journey. (R. E.G. Davies)

One of the best features of the 11-86 is the lower level baggage compartment, where passengers can stow carry-on items that are not needed during the journey. (R. E.G. Davies)

The compilation of this book would not have been possible without the cordial cooperation of the International Commercial Department of Aeroflot, under the direction of Vladimir Tikhonov, and with the supervision of Vladimir Masenkov, who assembled a team to provide data essential for the work. The team consisted of Vadim Suvarov, veteran pilot of the Great Patriotic War; Boris Urenovsky, Professor of the Civil Aviation Institute in Moscow; and Tatiana Vinogradova, once a senior flight attendant (she flew on the Tupolev Tu-114 to Havana and to Tokyo). Together the team helped to ensure that errors in early drafts were corrected and accuracy ensured.

Much of the Russian documentation was translated by Alex Kampf, an enthusiastic student of Aeroflot history. In Moscow, I received great support from my good friend Yuri Salnikov, television director of aviation documentaries and author of magazine articles on famous Soviet airmen. He introduced me to Vladimir Samoroukov, who examined my credentials and first approved the book project.

Vasily Karpy, editor of Vozduzhny Transport, proof-read the text and gave valuable advice. He also introduced me to Boris Vdovienko, photographer par excellence, from whose magnificent collection I was able to draw. Veteran pioneer pilot, General Georgy Baidukov, Valery Chkalov’s right hand on his epic 1937 polar crossing, gave me a personal insight into the workings of the old Aeroflot, and a first-hand account of the historic meeting with Josef Stalin in 1936.

I received generous help from many others. In Leningrad/St Petersburg, I was hosted by the Academy of Civil Aviation, where Professor-Director Georgy Kryzhanovsky, Deputy Director Anatoly Khvostovsky, Nina Nekrasovich, Irene Volkova, Vitaly Khalikov, and the Academy’s librarian, Natella Safronova, were most helpful. In Novgorod, thanks to the Chief of the Sub-Region, Anatoli Golovanov, and Deputy Chief Vladimir Bolovsky, I was able to sample the crop-spraying versatility of the remarkable Antonov An-2. In Khabarovsk, the

Vozduzhny Transport correspondent, Oleg Borisov, has been a catalyst for some thrilling research. Through the courtesy of Vladimir Skripnik, Director of the Far Eastern Region of Aeroflot, I learned much about the airline’s provincial operations, including a demonstration of the acrobatic prowess of the An-2. At Nikolayevsk-na-Amure, Valery Dolmatov, Head of the Nikolayevsk station and also a deputy to the Russian Parliament in Moscow, afforded me the extraordinary privilege of making a helicopter pilgrimage to the dignified monument on Chkalov (formerly Udd) Island; and I met Vadim Romanuk, local helicopter mechanic and historian, who inspired the erection of the monument. Later, Leonid Nagorny, who succeeded Skripnik in 1991 (and whose 50th birthday party I shall long remember), Vladimir Lenuk, Aleksander Glushko, and Vladimir Kuznetzov, also gave me much assistance. In Tyumen, Director Vladimir Illarionov and especially Mikhail Ponomarev opened my eyes to the helicopter capital of the world. At Krasnoyarsk, Deputy Director Boris Kovchenkov was most hospitable, as was Nikolei Klimenko at Yeneseisk. At Irkutsk, Vladimir Sokolnikov and Peter Osharov were generous hosts, and my guide to the excellent museum there was Professor-Doctor Yvgeny Altunin, aviation historian and author from Irkutsk University. Similarly, at Yakutsk, General Director, Vitaly Pinaev, Mikhail Vasilev and others introduced me to the special problems of operations in Yakutia, and to aviation historians Ivan Nygenblya and Vladimir Pesterev.

Back in Moscow, I was able to meet Genrikh Novozhilov, Igor Katyrev, Aleksander Shakhnovich, and Georgy Sheremetev, of the Ilyushin Design Bureau; Yuri Popov, Gleb Mahetkin, and Sergei Agavilyan, of Tupolev; and Aleksander Domdukov and Evegeny Tarassov, of Yakovlev. I interviewed veteran Aeroflot pilots such as Constantin Sepulkin and Aleksander Vitkovsky. Tatiana Vinogradova, Vasily Karpy, Yuri Salnikov, and Viktor Temichev arranged the programs of visits — no easy task during often-congested traveling schedules.

I must not forget the eminent British writers who have contributed so much to the annals of Soviet aviation history during times when information was most difficult to obtain. Veteran author and authority John Stroud, airline chronicler Klaus Vomhof, and technical specialist Bill Gunston have all produced pioneering works that have become standard references (see bibliography) for latterday writers such as myself. Bob Ruffle, stalwart of Air-Britain’s Russian Aviation Research Group, generously supplied pre-war fleet data and scrutinized the text. Carl Bobrow and Harry Woodman provided expertise on the Il’ya Muromets and Paul Duffy’s camera work and information bulletins on post-U. S.S. R. developments (not to mention his scoop in ascertaining the Lisunov Li-2 production total) have been invaluable.

The Ukrainian airline took over the Junkers operation (see page 15) which, with the Zakavia franchise, gave it almost the whole of the southern part of the European U. S.S. R. as its traffic catchment area. Uzkrvozdukhput carried 3,050 passengers in 1928.

But its very success perhaps fell foul of government policy centered in Moscow. One of the items contained in the first Soviet Five-Year Plan was to create an all-Soviet airline which, in 1930, not only inherited the Russian Dobrolet, but engulfed Ukrvozdukhput as well.