Technical Slowdown

Although the ANT-9 of the late 1920s had been on a par with the commercial aircraft of other countries; and the ANT-6 had been an adequate heavy lifter, Soviet designers lost momentum during the 1930s. Kalinin was executed. Tupolev himself spent much of his time under house arrest, and escaped being shot only by the intervention of, of all people, Beria, head of the secret police.

Buying the Best

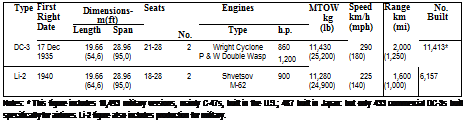

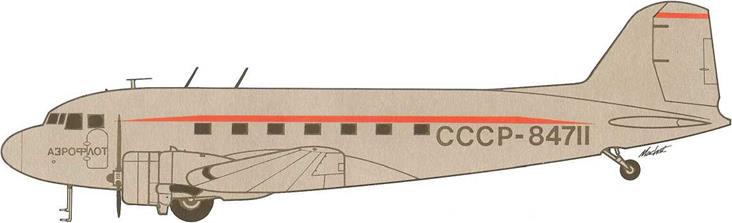

In August 1935, AMTORG (American Trading Organization) in New York, took delivery of the first DC-2 (NC14949, msn 1413) and Boris Lisunov was sent to California to prepare for the licensed production of the Douglas twin. The Soviet-built Douglases were first designated PS – 845 (Pashazhyrski Samolyet, or passenger aircraft), and from 17 September 1942, Lisunov Li – 25. These were standard DC-3s, with a right-side – entry door. By the end of World War II, 2,258 had been built. The type remained in production until 1954, by which time a total of 6,157 had been built at Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Lend-Leases

After the Nazi invasion of the summer of 1941, much of western Russia and the Ukraine had been devastated or pillaged. In a mighty display of determination and improvised organization, all the aircraft production lines in Europe were moved eastwards to cities beyond the Ural Mountains. This massive logistics task took many months, and meanwhile the Air Force had to be reinforced.

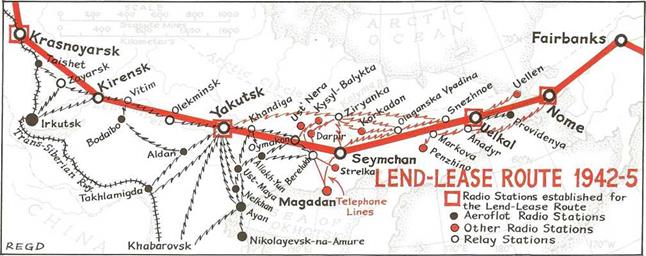

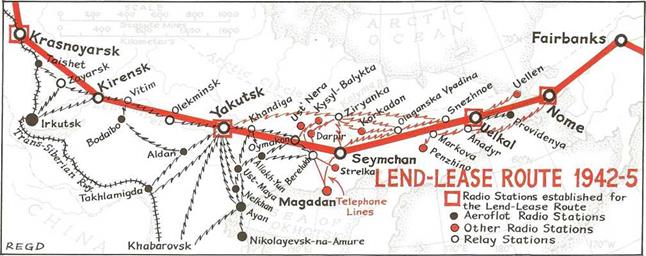

At an Allied conference in Moscow on 31 July 1941, Harry Hopkins, President Roosevelt’s special envoy, laid the foundations of what was to become the Lend-Lease Program. Slow to get under way at first — few aircraft arrived in time for the Battle of Moscow, and these were from Britain, via Murmansk — the unprecedented machinery of the historic airlift began on 29 September 1942, when the first Bell P-39 Airacobra left Fairbanks, Alaska, and arrived in time to go into action early in October.

Of the 18,700 aircraft supplied under the Allied Lend – Lease program, 14,750 were flown along this route, by U. S. pilots to Fairbanks, where Soviet flyers took over. Of these, over 4,900 were P-39 Airacobras, 2,400 P-63 Kingcobras,

2,900 Douglas DB-7/A-20 Havocs, and 860 North American B-25 Mitchells. About 640 were lost in transit. The Lend – Lease aircraft accounted for 12% of the 136,800 of all types used by the Soviet Air Force in the Great Patriotic War.

Of the several other types, other than those mentioned above, 700 were Douglas C-47s, the most widely used of the military variants of the DC-3 workhorse transport airplane. They were used everywhere. The Soviet pilots liked them as much as did the U. S.A. A.F. ‘Gooney Bird’ and the R. A.F. Dakota flyers. And they were to make a solid contribution to Aeroflot’s recovery after the conflict came to an end. On 1 March 1946, for instance, the 14th Cargo Aircraft Group of Aeroflot was formed at Yakutsk. Fifteen C-47s were transferred from the Soviet air fleet, together with, remarkably, three Junkers-Ju 52/3m’s that had been captured on the eastern front.

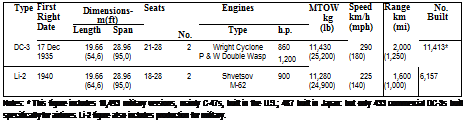

COMPARISON OF DOUGLAS DC-3 AND LISUNOV LI-2

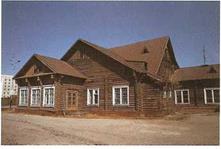

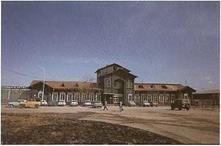

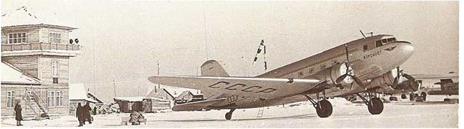

The old Yakutsk terminal building, in traditional Russian wood construction, first erected for the Lend-Lease program, is still there, as this photo, taken in 1992, shows. Just down the street is the original building which housed the offices of the Lend-Lease program during the vital years, 1942-1945. (R. E.G. Davies)

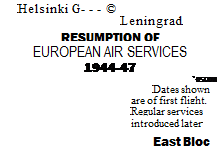

Resumption of European Services

The Soviet Union emerged from World War II (The Great Patriotic War) weakened by its sustained and intensive efforts to beat the Nazi war machine into the ground. Aeroflot had to re-group as the national flag carrier, as Moscow began to isolate itself from its allies in the west, at the same time trying to dominate the countries on its borders, simultaneously spreading the creed of communism and fashioning a cordon sanitaire to guard against a repetition of the events of 1920.

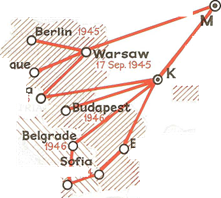

In 1944, the U. S.S. R. had declined an invitation to attend the historic Chicago Conference, at which most of the world’s nations hammered out the basis for what was to become the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). The Five Freedoms of the Air were not wholly accepted in Moscow, where, nevertheless, plans were quickly made to spread Aeroflot’s wings westwards. By the end of 1945, services had been reinstated, or started anew, to most of the capitals of eastern and central Europe, and also to Teheran. At home, the trans-Siberian and other main arterial routes were revived, and the social work in the Arctic, which had continued even during the war, was maintained.

Like the British, French, and nations other than the exceptionally well-equipped United States, the U. S.S. R. had to make the best with what it had: the trusty Lisunov Li-2s and the ex-Lend-Lease Douglas C-47s.

Baidukov Has PrabBems

The Fourth Five-Year Plan had provided for ambitious Aeroflot expansion, with a target of 175,000km (110,000mi) of routes

|

The Ilyushin 18, first flown on 30 July 1947, was a 60-seat four – engined airliner which never went into production. It was too large for the traffic of the day and demanded ground support which would not be available for years, (photo: Ilyushin Design Bureau)

|

throughout the Soviet Union. Yet to service this great plan, Aeroflot had little more than a large fleet of Li-2s for the main routes, and hundreds of little Polikarpov Po-2s.

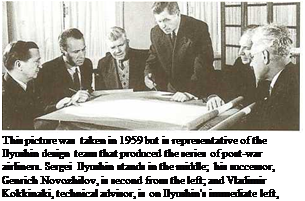

This was the situation confronting Georgy Baidukov, veteran crew member of the Chkalov trans-Polar flight of 1937, and Stalin’s personal envoy to the United States during the war years, when he was put in charge of Aeroflot in 1947. The equipment upgrading prospects were gloomy. Sergei Ilyushin had made preliminary drawings for what was to become the Ilyushin 11-12 as early as 1943, and this unpressurized tricycle-geared twin made its first public appearance on 18 August 1946. But this was no ‘DC-3 Replacement’.

On the ground, airports were totally inadequate, with poor runways, bad passenger buildings, and maintenance, as often as not, in the open. Baidukov effectively made his point by taking a party of officials, including Mikoyan, on a proving flight from Moscow to Khabarovsk. The shortcomings were only too obvious, and this inspection trip no doubt had some effect on subsequent actions taken with the next Five Year Plan.

The First Ilyushins

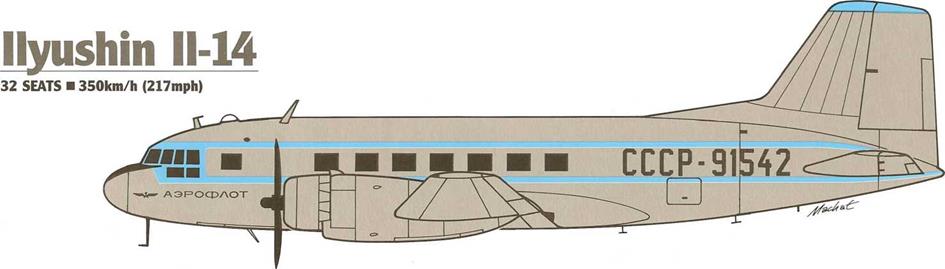

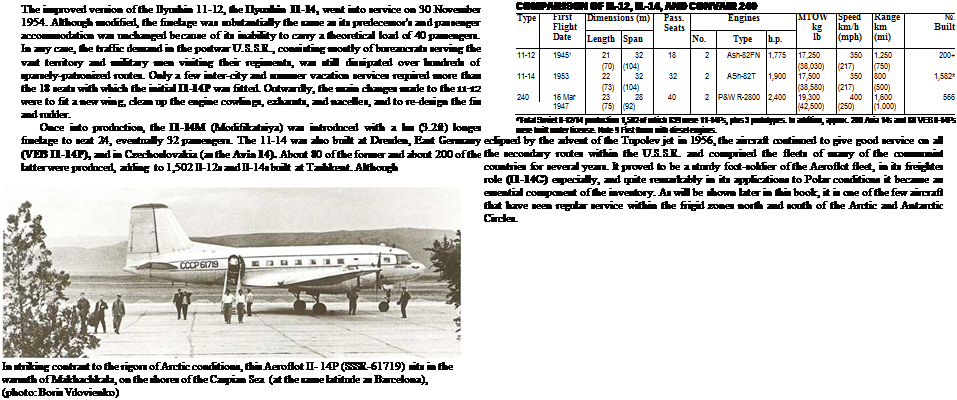

Making the best of a sub-standard inventory, Baidukov introduced the 11-12, on a few selected routes, on 22 August 1947, and more widely in the following year when the summer schedules started on 23 May. Some relief was expected from the 60-seat four-engined Ilyushin 11-18 (the piston-engined one, not the later turboprop) but although it made its first flight on 30 July 1947, and went into service — again on selected trunk routes — at the end of 1948; it was too big and complicated for the traffic and ground infrastructure of the day, and very few were built. They were withdrawn from service by 1950.

Baidukov fought off official skepticism and introduced flight attendants on the more important routes; and he witnessed the introduction of the amazing 12-seat Antonov An-2 biplane, which made its first flight in March 1948.

Widening Responsibilities

After two and a half years, during which the Politburo often accused him of poor management, Baidukov resigned — without incidentally apologizing for anything, a procedure that was the expected protocol in those times. He had been sorely tried. For apart from the problems of inadequate aircraft, airfields, ground services and engineering staff, pilots who were apt to take on too much vodka and not enough fuel, and a meager budget, he had been given additional responsibilities.

Back in 1932, Aeroflot had taken on the task of agricultural support in crop-dusting and crop-spraying, an activity in which the U. S.S. R. had been a pioneer. In 1937, it had added ambulance and medical supply flights to supplement its other work, with a ‘flying doctor’ service. Now, on 23 September 1948, it added forestry patrol, ice reconnaissance and water-bombing; and on 30 November 1949, it was given the additional task of supporting fishing fleets by surveying the seas to locate shoals of fish.

Yet in spite of all the difficulties, Aeroflot must have been doing something right. In 1950, it carried 3.8 million passengers, and flew over a network of 75,600km (47,000mi).

18 SEATS □ 225km/h (140mph)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

Joint Ventures

The term joint venture’ has become part of the language of international commerce during the past few years,. But such a device was common in airline associations back in the early 1940s when, for example, Pan American Airways set up such partnerships in Latin America. In exchange for certain privileges, such as exclusive mail contracts, Pan Am would provide the technical and administrative expertise, and supply aircraft at bargain rates, to set up local airlines, ostensibly as national carriers, but in reality Pan Am subsidiaries.

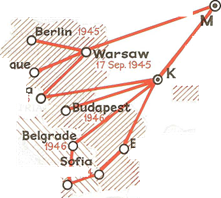

During the latter 1940s, as Europe rearranged itself into two halves of political persuasion, the U. S.S. R. took a leaf out of Pan Am’s book, and set up similar airlines in eastern Europe, with Aeroflot as Big Brother. Ironically, the ubiquitous Douglas DC-3, in its Lisunov Li-2 disguise, was invariably the basis of the small post-war communist-directed airline fleets, just as with Pan American on the other side of the world.

Tie First Exports

Interestingly, therefore, a California-designed aircraft, license-built in the U. S.S. R., was the key factor in this particular channel of political influence. The Lisunovs were the only aircraft in adequate supply in 1945 and 1946; but they were to be the basis for a secure Soviet foothold in what was later to become known as the Six-Pool group of eastern European airlines. This foothold was to prevail for the next half-century.

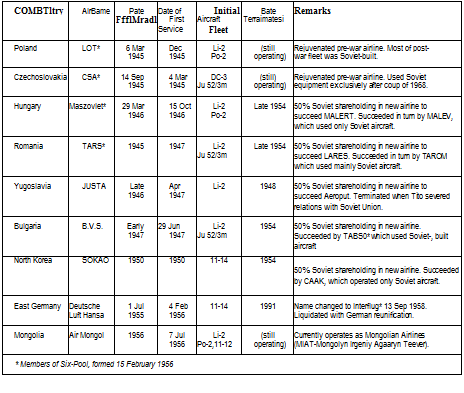

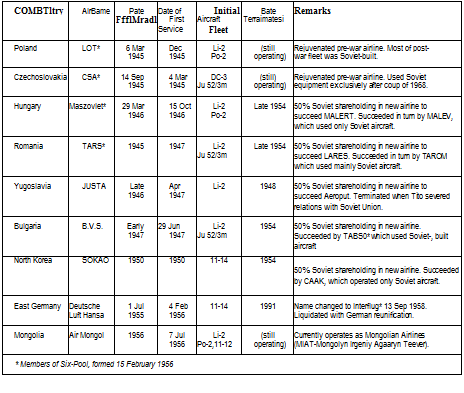

JOINT VENTURE AIRLINES IN POST-WAR SOVIET SATELLITE COUNTRIES

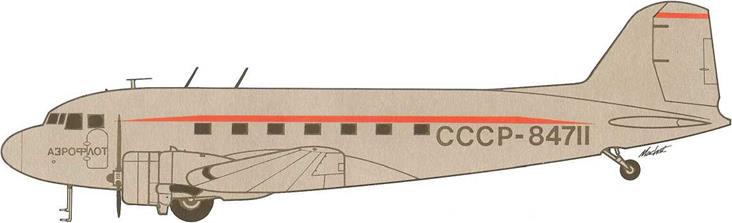

This Lisunov Li-2 is pictured atMirnyy, the center of the diamond industry in the Yakut autonomous republic of eastern Siberia in 1961. The ‘Russian DC-3’ performed sterling work for over a quarter of a century, and the Yakuts held it in such high esteem that they have preserved one on a pedestal at Chersky, near the delta of the Kolyma River, on the East Siberian Sea of the Arctic Ocean, 240km (150mi) north of the Arctic Circle. (Y. Ryumkin, courtesy John Stroud)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

JUNKERS-W 33 IN SOVIET SERVICE

JUNKERS-W 33 IN SOVIET SERVICE

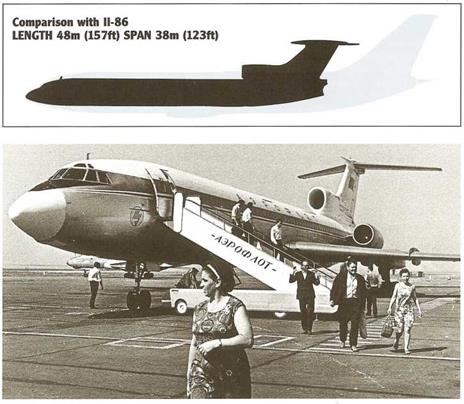

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)