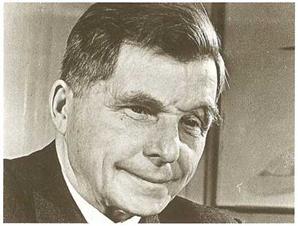

Author

This book started a long time ago. In the late 1950s, when I was researching material for my History of the World’s Airlines, I was fascinated by the Soviet airline that seemed to be performing an enormous task, but of which little was known. An almost impenetrable curtain shrouded all but a trickle of information from Moscow. Travel was severely restricted, and even in the decades that followed, was scanty and sporadic, to selected tourist destinations. In 1988, however, when Mikhail Gorbachev drew aside the curtain, an opportunity seemed at last to be in sight, and I once again approached the Soviet Embassy for permission to visit Aeroflot.

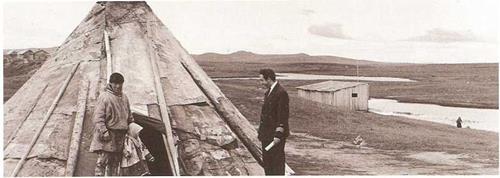

In 1990, I made the first reconnaissance to Moscow, and asked to see the workings of the secondary, feeder, and bush services of the vast domestic network. The International Department responded admirably. I visited the Far Eastern Division, flew in the Antonov An-2 and An-24, and, in a Mil Mi-2, made a pilgrimage to the dignified monument to the Chkalov crew on the former Udd Island. I began to feel the pulse of Aeroflot, to meet its pilots, its managers, and its staff, and to realize that this huge airline was as dedicated to its task as any other airline of world stature.

Returning to Moscow, I was privileged to sit at the desks of the late Andrei Tupolev and Sergei Ilyushin, and to visit the museums of the great design bureaux. Welcomed everywhere with courtesy and enthusiasm, my appetite was whetted for more.

In 1991, I cohtinued the mission. I visited the Leningrad Aviation Academy, did some simulated cropdusting at Novgorod, and rounded off a round-the-world trip (all on Aeroflot) by visiting old friends in Khabarovsk. On the return to the U. S., I made the decision to begin this book.

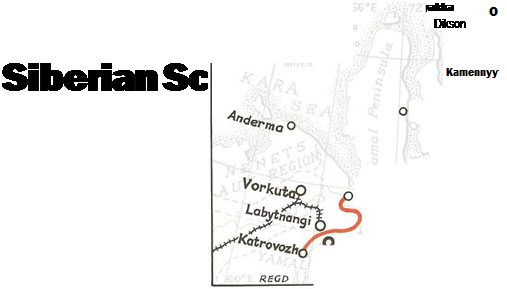

In 1992,1 made a whistle-stop tour of Siberia (by this time the Soviet Union had become the CIS) and gained first-hand knowledge of the array of different roles played by Aeroflot, in agriculture, forestry, fishing patrol, ambulance and emergency work, and construction, especially in oilfields, pipelines, power lines, and railroads. Everywhere, I enjoyed visits to museums. Every region of Aeroflot has its historians, justly proud of their heritage.

Telling the story, and meeting some of the people who have contributed to it, has been an exciting and stimulating exercise. Finally, I must record the great pleasure of working once again with the ‘Old Firm’ who produced the previous books in the series: Pan Am, Lufthansa, and Delta. To consult, to review, to plan, and to organize — and yes, sometimes to argue — with my good friends artist Mike Machat and producer/editor John Wegg has been a rewarding, (if at times strenuous), and totally fulfilling experience.

— R. E.G. Davies.

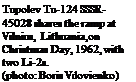

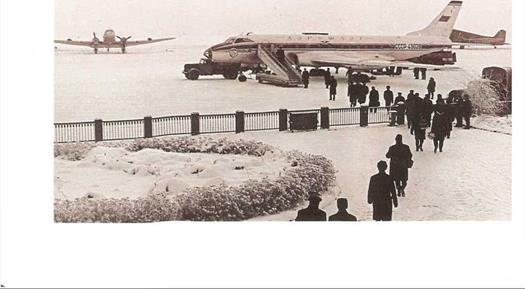

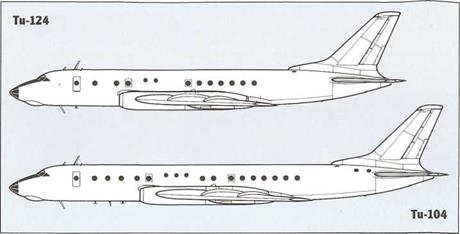

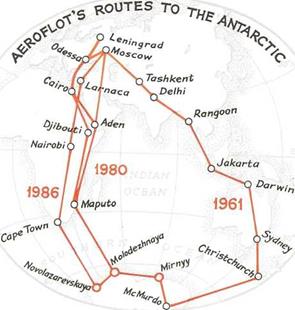

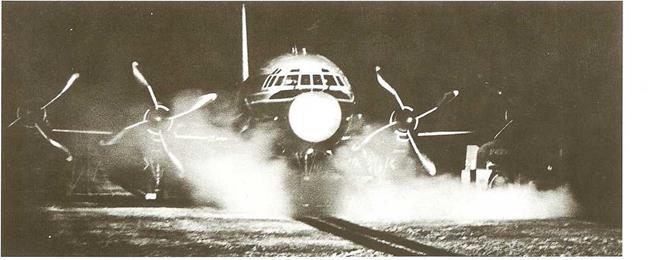

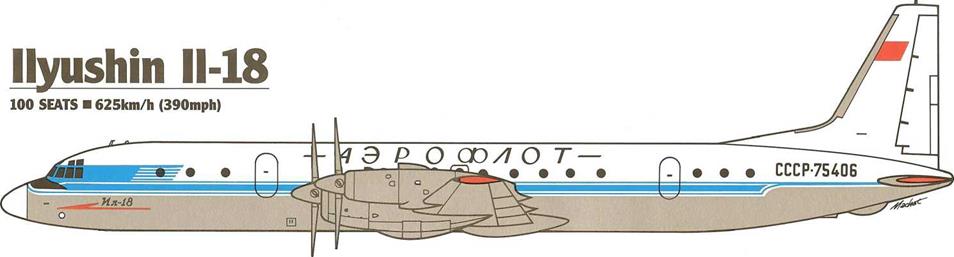

With a variety of airliners coming off the production lines (see opposite) Aeroflot entered the 1960s with prospects of expansion and upgrading of equipment in all directions. On 3 January 1960, it took over Polar Aviation (Aviaarktika) and directed attention to the northern routes, to new settlements on the Arctic Sea, and a new route to the Far East. On 24 April, a Tupolev Tu-114 non-stop Moscow-Khabarovsk schedule inauguration immeasurably extended the range potential. On 15 December 1961, a specially-equipped Ilyushin 11-18 became the first airliner to fly to Antarctica, and this aircraft opened up new routes to several African countries during the next few years. The Tupolev Tu-104, too short in range for use on transocean routes, was nevertheless able to carry Aeroflot’s flag to south-east Asia, with a service, opened on 31 January 1962, to Jakarta, via Tashkent, Delhi, and Rangoon. By this time, Aeroflot was carrying more than 20 million passengers each year (with fares at railroad levels) with a total fleet of about 2,000 aircraft.

With a variety of airliners coming off the production lines (see opposite) Aeroflot entered the 1960s with prospects of expansion and upgrading of equipment in all directions. On 3 January 1960, it took over Polar Aviation (Aviaarktika) and directed attention to the northern routes, to new settlements on the Arctic Sea, and a new route to the Far East. On 24 April, a Tupolev Tu-114 non-stop Moscow-Khabarovsk schedule inauguration immeasurably extended the range potential. On 15 December 1961, a specially-equipped Ilyushin 11-18 became the first airliner to fly to Antarctica, and this aircraft opened up new routes to several African countries during the next few years. The Tupolev Tu-104, too short in range for use on transocean routes, was nevertheless able to carry Aeroflot’s flag to south-east Asia, with a service, opened on 31 January 1962, to Jakarta, via Tashkent, Delhi, and Rangoon. By this time, Aeroflot was carrying more than 20 million passengers each year (with fares at railroad levels) with a total fleet of about 2,000 aircraft.

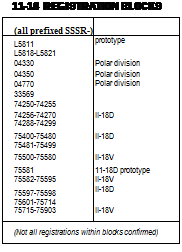

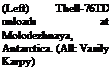

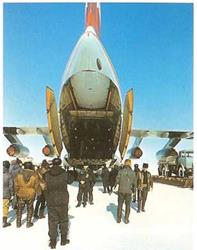

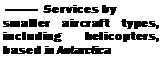

In 1980, a new route was forged to Antarctica. Previously (see map) the Soviet aircraft had flown the same path as the American and Australian flights, from Christchurch, New Zealand (which boasts the only ticket counter with Antarctica on the destination board); but this had entailed a long flight through Asia. Now, with a special version of the Ilyushin 11-18, the 11-18D, under the command of B. D. Grubly, Moscow was connected by a shorter route, through Africa (see map) made possible by the ability of the I1-18D to cover the longer distance from Maputo to Molodezhnaya — 5,000km (3,100mi) with no en route alternates. This flight, in support of the 25th Antarctic Expedition, made the outbound journey from 10-13 February and returned from 19-23 February. The 45,600km (28,380mi) round trip was made in 78hr 54min flying time.

In 1980, a new route was forged to Antarctica. Previously (see map) the Soviet aircraft had flown the same path as the American and Australian flights, from Christchurch, New Zealand (which boasts the only ticket counter with Antarctica on the destination board); but this had entailed a long flight through Asia. Now, with a special version of the Ilyushin 11-18, the 11-18D, under the command of B. D. Grubly, Moscow was connected by a shorter route, through Africa (see map) made possible by the ability of the I1-18D to cover the longer distance from Maputo to Molodezhnaya — 5,000km (3,100mi) with no en route alternates. This flight, in support of the 25th Antarctic Expedition, made the outbound journey from 10-13 February and returned from 19-23 February. The 45,600km (28,380mi) round trip was made in 78hr 54min flying time. 150 TONS ■ 800km/h (500mph)

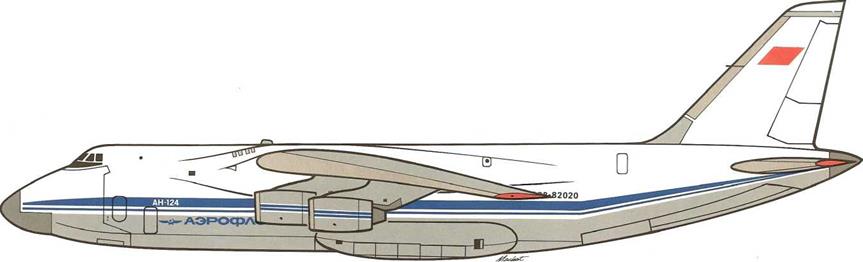

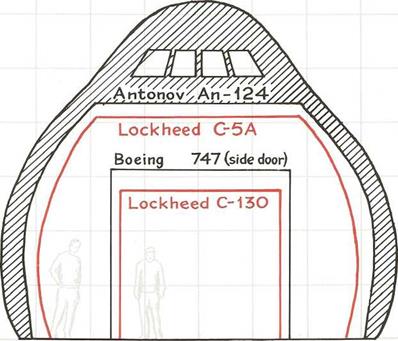

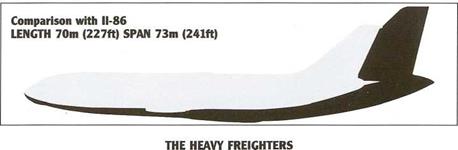

150 TONS ■ 800km/h (500mph)

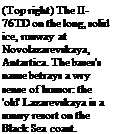

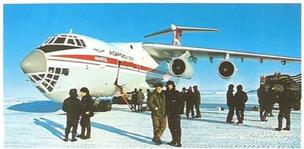

The ground staff at Molodezhnaya must have heard the story of the English gardener who, when asked by an American tourist how he had produced such a perfect lawn, suggested that it may have been the result of mowing it once a week, and rolling it once a week… for 500 years. Overcoming difficulties of alternate melting during long summer days of unbroken sunshine and crusting of surfaces with repeated freezing, the ground staff rolled and rolled and rolled the runway… for a whole year. The 11-76 landed and took off successfully.

The ground staff at Molodezhnaya must have heard the story of the English gardener who, when asked by an American tourist how he had produced such a perfect lawn, suggested that it may have been the result of mowing it once a week, and rolling it once a week… for 500 years. Overcoming difficulties of alternate melting during long summer days of unbroken sunshine and crusting of surfaces with repeated freezing, the ground staff rolled and rolled and rolled the runway… for a whole year. The 11-76 landed and took off successfully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis