On September 6, 2002, the Russians announced a delay in the launch of Progress M1-9, from September 20 to September 25, caused by problems with the spacecraft’s computer and its KURS docking system antenna. The relevant hardware was returned to RCS Energia for repair on September 3.

Even as Progress M1-9 was being prepared for flight, officials at Energia released details of the company’s dire financial position. Valeri Ryumin announced that the company had ten Soyuz and Progress vehicles in manufacture but contractors were reluctant to release vitally needed parts to complete the spacecraft to a company that already owed millions of roubles to the bank and its contractors. He stated that the $79 million that Energia would receive from the Russian government for FY2003 would be only half that required to finance the company’s commitment to ISS for the year. This consisted of two Soyuz TMA spacecraft and four Progress Ml vehicles. Ryumin blamed the Russian government for not meeting its commitment to ISS and even went so far as to suggest that the station be powered down and left unmanned between Shuttle flights. American officials once again ignored their own unilateral disregard for the legal contract between the ISS partners and replied to the Russian news by saying that they expected Energia to meet their contractual commitments to ISS.

Progress Ml-9 was launched at 13: 37, June 26, 2002, and was station-keeping 1 km from ISS on September 28. At that time the spacecraft was used to test the twoway flow of data between the KURS automatic docking system in the two spacecraft. Progress docked automatically to Zvezda’s wake, at 13: 01, September 29. The internal hatches were opened that afternoon, but unloading did not begin until the following day.

STS-112 DELIVERS THE STARBOARD-1 ITS

|

STS-112

|

|

COMMANDER

|

Jeffrey Ashby

|

|

PILOT

|

Pamela Melroy

|

|

MISSION SPECIALISTS

|

David Wolf, Piers Sellers, Sandra Magnus,

|

|

Fyodor Yurchikhin

|

STS-112 Atlantis had originally been planned for launch on August 22, 2002, but this was cancelled when cracks were found in the cryogenic propellant duct liners in the SSMEs of each of the Shuttle orbiters, leading to the grounding of the entire Shuttle fleet. Following an engineering review of the cracks, the launch was set for not earlier than September 26. Over August 10-12 the cracks were repaired, by welding and polishing. By August 18, the three SSMEs had been installed in the rear of Atlantis.

On August 22, the launch was set for October 2, 2002, but during the final preparations for launch Hurricane Lilli threatened to make landfall and threaten Houston, the location of NASA’s MCC. As there was no way of telling how the hurricane might affect control of the flight, it was decided to delay for 24 hours. On October 2 that was extended for a further four days as the control centre in Houston was shut down and control of ISS handed over to the Russians for the duration of the storm. The hand-over meant a restriction in communications as the Russian network could not handle the station’s Ku-band and S-band channels. As Korolev was also unable to monitor the ability of the American P-6 ITS photovoltaic arrays to track the Sun, the arrays were locked in position. Houston resumed control of ISS on October 4, and it was returned to full operation. The problems caused the Russians to cancel a test of Progress M1-9’s thrusters on October 4, and a station re-boost manoeuvre on October 5. The new STS-112 launch date was set for October 7.

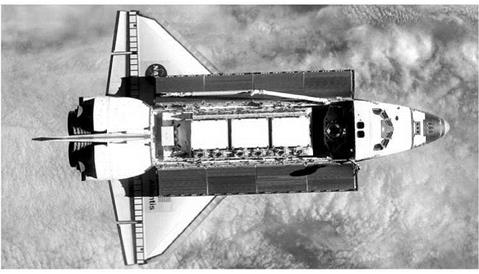

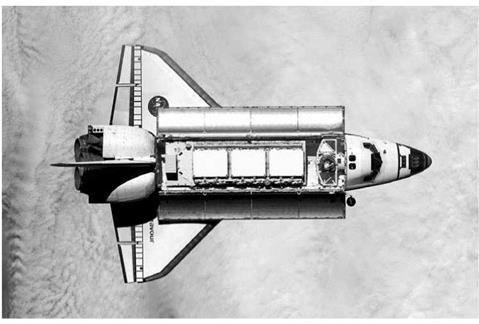

On that date Atlantis lifted off at 15: 46, to deliver the Starboard-1 (S-1) truss to the station. Throughout the launch a small camera mounted on the ET showed the external view looking back past Atlantis. Similar videos captured on throw-away rockets had proved very popular with the public. As the Shuttle lifted off, ISS was over the Pacific Ocean and the Expedition-5 crew were on their 122nd day onboard and their 124th day in space.

Post-launch inspection showed that all ten back-up pyrotechnics in the SRB hold-down bolts had failed to ignite. Each bolt had a primary charge to sever the bolt at lift-off. The back-up charges were then fired a fraction of a second later, to ensure all of the bolts were separated. On this occasion no serious damage was sustained because all ten primary charges had fired. NASA engineers acknowledged that the problem was most likely in the transmission, or receipt of the firing signal for the secondary charges, an echo of the problems with the wiring in the Shuttle fleet, which had grounded the entire fleet in 2000.

Having achieved orbit, Atlantis followed the standard rendezvous pattern while her crew performed all of the usual activities in advance of docking with ISS. They also performed their own solo experiment programme. As Atlantis performed the rendezvous Korzun, Whitson, and Treschev were unloading Progress M1-9 and packing items for return to Earth on STS-112.

Ashby performed a manual docking with PMA-2 on Destiny’s ram at 11: 17, October 9. Following pressure checks Whitson asked Ashby if he had brought the salsa that she had asked for. When Ashby replied that he had, Whitson conceded, “OK, we’ll let you in.’’ The hatches between the two spacecraft were opened and the Shuttle’s crew left Atlantis and moved into Destiny, the first visitors to ISS in four

|

Figure 23. STS-112 crew (L to Right) Sandra Magnus, David Wolf, Pamela Melroy, Jeffrey Ashby, Piers Sellers, Fyodor Yurchikhin.

|

|

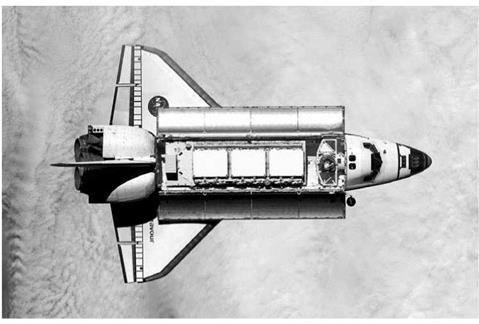

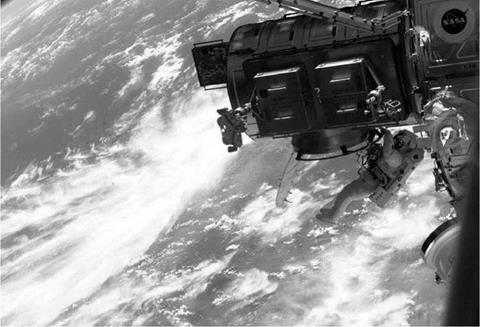

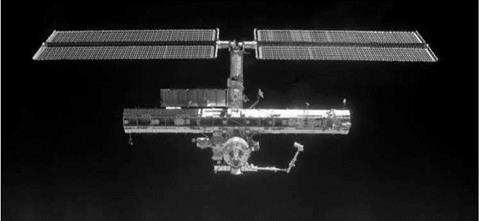

Figure 24. STS-112: Atlantis delivers the Starboard-1 Integrated Truss Structure.

|

months. The two crews immediately began work preparing for the installation of the S-l ITS, and the first of the three EVAs associated with it.

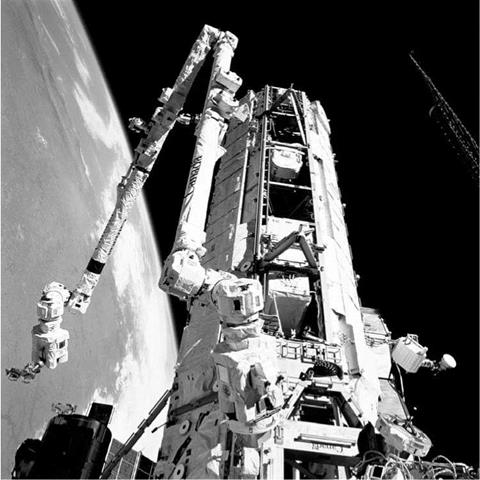

On October 10, Whitson and Magnus used the SSRMS to lift the l5-metre-long, 14-tonne S-l ITS out of Atlantis’ payload bay and manoeuvre it into a position where it could be soft-docked with the Starboard end of the S-0 ITS, which was mounted on Destiny’s zenith CBM. Once soft-docking had been achieved motorised bolts were driven into place to secure the two units together at 09:36.

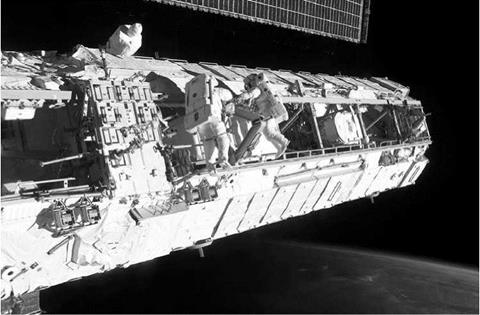

Wolf and Sellers exited the Quest airlock at 11:21. Wolf rode a foot restraint mounted on the SSRMS while Sellers used his hands to move around. Wolf connected power, fluid, and data umbilicals between the 2 ITS elements while Sellers used a motorised tool to undo the 18 launch locks on the 3 space radiators mounted on S-1, allowing them to be oriented for maximum cooling when they were deployed. The two then worked together to deploy an S-band antenna on the S-1 ITS. Wolf placed the antenna in the end-effector of the SSRMS and it was then moved into place near the join between the S-1 and S-0 ITS elements. Sellers held the antenna in place while Wolf secured the bolts that would hold it there.

As they passed over the Pacific Ocean Sellers looked at Earth and asked, “Where am I? Wow, its too beautiful for words, unbelievable!” After a short break to take in the view he remarked, “That’s it, back to work.’’

They then worked together to release the bolts that held the Crew and Equipment Transition Aid (CETA) to the S-1 truss and configured its brakes. The CETA would

|

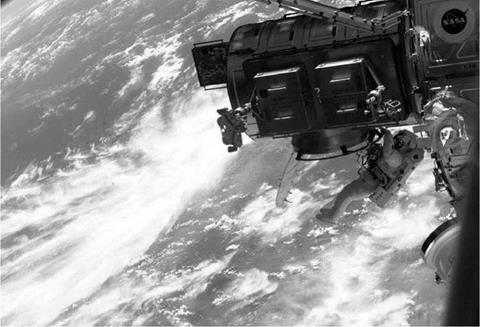

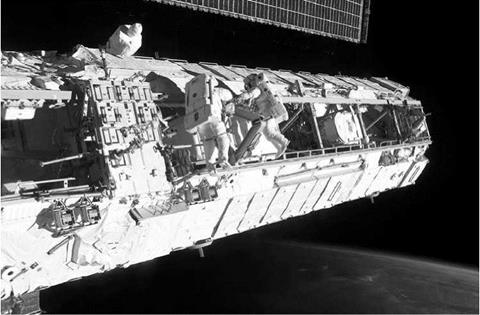

Figure 25. STS-112: Piers Sellers wears an American Extravehicular Mobility Unit near the open hatch of the Quest airlock.

|

|

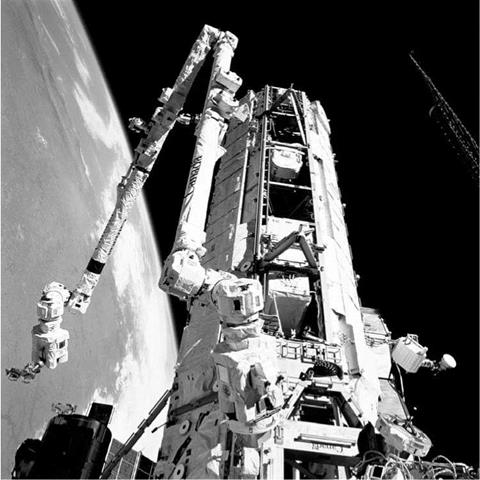

Figure 26. STS-112: The S-l Integrated Truss Structure. The SSRMS is mounted on the MBS which runs along a track on the ram face of the Starboard-0 Integrated Truss.

|

be used to transport future EVA astronauts and their equipment along rails travelling the length of the ITS when it was complete. Their final task was to fix the S-l outboard nadir exterior camera in position. At that point the SSRMS suffered a mechanical failure and the two astronauts completed their tasks without it. This was the first of two cameras to be fixed on the S-l truss for use in future EVAs. The first STS-112 EVA ended at 18: 22, after 7 hours 1 minute. With the two astronauts back in the airlock Houston told them, “You guys did an awesome job. You saved us.” Both crews took time out to relax on October 11, before beginning the task of transferring equipment from Atlantis to Destiny. Wolf and Sellers prepared the equipment for their second EVA, planned for October 12. During the evening both crews answered questions from the Russian and American media. Questioned about their first EVA Wolf replied, “I tell you what, it’s pretty tough. We got plenty tired, and I believe our heart rates got up over 170 during that task.’’ On the subject of EVA-2 he added, “We’re ready to go again.’’

Sellers, who had been on his first EVA, described his first view through the open airlock hatch:

“I was completely knocked out of my socks, which were luckily in my suit. I could see a landscape with clouds and a river, and it was just huge. It was fantastic. So the first five minutes, I was pretty much non-functional. My little brain was overloaded.’’

The principal task of the second EVA had been identified by engineers working with the ITS elements on the ground. They found that in some of the older ISS plumbing pressure could build up, and the pipes might not twist and disconnect as planned, thereby leading to a destructive failure. After many hours of work, a workaround was designed for the problem: fit Spool Positioning Devices (SPDs) on the plumbing connection to release the pressure.

After breakfast and prior to the second EVA, Ashby and Melroy fired Atlantis’ thrusters to raise the station’s orbit. EVA-2 then began at 10:31, October 12. Following preparations, Wolf and Sellers worked to further prepare the CETA for use during future EVAs. They also installed 22 Spool Positioning Devices on fluid lines in an attempt to prevent pressure build-up in the pipes preventing the correct use of the quick-disconnect fittings if required in the future. When he fitted the first device Wolf reported that there had already been a pressure build-up in the pipe and he had released it when he fitted the SPD. As Wolf put it, “I heard it burp.’’ Two other SPDs could not be fitted because the fluid lines “were of a different configuration” from that on which the SPD was designed to fit. What the euphemism in the NASA STS-112 Status Report actually meant was that Wolf had discovered that the two pipes in question had been launched with certain parts not installed. That discovery came as a surprise to everyone. Some of the joints were in positions that were hard to reach, but Sellers achieved the task and was congratulated from inside ISS by Melroy, “It is quite possible you’re the only person in the astronaut office who could have done that task.’’ The two astronauts also connected the ammonia cooling system to the S-1 ITS radiators and fitted a camera on the exterior of Destiny. The EVA ended approximately 30 minutes early, at 16: 35, after 6 hours 4 minutes.

During the end-of-day press conference, mission planners explained why the SSRMS had failed during the first EVA. The SSRMS and the MBS both worked on separate software programmes, which have to work together. If they were not correctly synchronised, then the entire unit stopped working. To ensure that two software programmes were synchronised required both the SSRMS and the MBS to be powered off and then powered back on in order to reset them, like re-booting a computer. There had not been enough time to do that before EVA-2, but Houston expected the MBS/SSRMS combination to be available for use during EVA-3.

October 13 was spent on equipment transfers and repairs. The Expedition-5 crew made a temporary repair to the TVIS, which was returned to a usable condition, despite the fact that they found a broken cable associated with the gyroscope, which would require a new one to be delivered on a future Shuttle, or Progress. The radiators on the S-l ITS were rotated into position, but their deployment was cancelled after adjustments were required to the tolerance levels of protective circuits used to monitor the initial stages of deployment. The time required to make those adjustments meant that Houston could no longer watch the deployment live, so it was delayed until the following day. Wolf and Sellers made their preparations for EVA-3, scheduled for October 14. During the afternoon press conference Whitson told how she had shared the new salsa delivered by STS-112 with her Expedition-5 crewmates. She also explained how her taste for certain foods that she enjoyed eating on Earth had changed in space so that she no longer enjoyed them. It was a common complaint among long-duration crews that food tasted extremely bland in space. Therefore, strong-flavoured food, or sauces such as Whitson’s salsa, became popular among these individuals.

That day began with the de-orbiting of Progress M-46 at 04: 34. Ashby and Melroy also performed a second re-boost manoeuvre commencing at 07: 20. The two series of manoeuvres had placed the station in the correct orbit to receive Soyuz TMA-1 later in the month, but this second manoeuvre used sufficient propellant to prompt Houston to reduce the planned 360° post-docking fly-around of ISS to just 180°, before Melroy performed the standard separation manoeuvre.

Houston then commanded the middle of three radiator panels on the S-1 ITS to deploy. As it reached its full length the crew played a recording of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus and Houston commented, “That’s very appropriate music.’’ The remaining two radiators were scheduled to be opened in 2003, at which time their heat-shedding function would be activated.

Wolf and Sellers began EVA-3 at 10: 11. Their first task was to remove the bolt that had prevented the cable cutter on the Mobile Transporter, mounted on the S-0 Truss, from activating at the end of the STS-111 flight. Next, they fitted ammonia lines between the S-0 and S-1 ITS elements and removed structural support clamps that had held the S-1 ITS in place during launch. At one point 46-year-old Wolf remarked, “We’re over the hill.’’ He quickly added, “I mean over the hill on the station.’’ Sellers, 47, replied, “No comment.’’ They also fitted two more SPDs to the pump motor assembly that circulated the ammonia throughout the cooling system. This was a “get-ahead’’ task, carried out because the two men had completed their primary tasks well ahead of schedule. As the EVA drew to a close Houston told them, “You guys are doing a great job. Our only concern is that you’re making it look too easy for us.’’ The EVA ended at 10: 11, after 6 hours 36 minutes.

Next day, both crews were given some free time to spend together before the STS-112 crew began preparing for their departure. While the final items were transferred between the two spacecraft, Ashby and Whitson worked together to replace a humidity separator in the Quest airlock. That evening the two crews said their farewells. Whitson and Magnus hugged each other as they said goodbye. When it came to saying goodbye to her good friend and remaining in orbit for a further month, Whitson commented, “I didn’t know it was going to be so hard.’’

|

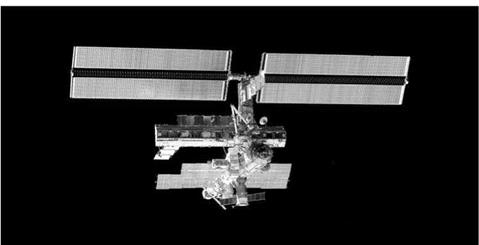

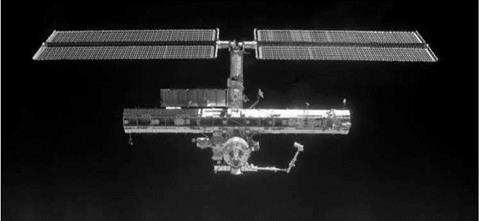

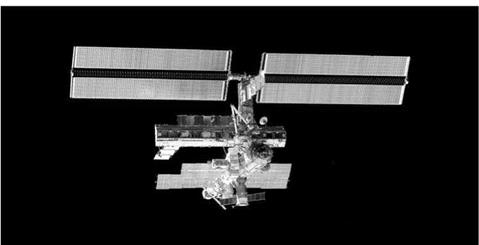

Figure 27. STS-112: As Atlantis departed the International Space Station, the Starboard-1 Integrated Truss Structure was clearly visible.

|

Melroy thanked Whitson and her colleagues for making the STS-112 crew welcome onboard the station and then concluded with, “You look wonderful. You look great. We miss you. Come home soon.” Ashby led his crew back to Atlantis and the hatches between the two vehicles were sealed. Both crews spent the night in their individual spacecraft. In Houston, mission manager Robert Castle told a press conference, “Overall, things are going very, very well, and I don’t think they could have done better.’’

As Atlantis passed over the Russia/Ukraine border Melroy told controllers, “We want to stay.’’ But they could not stay, and she undocked Atlantis from Destiny’s ram at 09: 13, October 16, and completed the reduced 180° fly-around manoeuvre to allow the other members of the crew to photograph ISS with the S-1 Truss in place. Melroy then performed the separation manoeuvre to allow the two spacecraft to drift apart under the influence of orbital mechanics.

October 17 was spent packing everything away in preparation for retrofire. Houston told the astronauts, “Just to make you jealous, it’s [the temperature] in the 50s here in Houston, and the weather is absolutely gorgeous, the air is dry.’’

As Atlantis continued to fall through the vacuum of space, Ashby replied, “It’s pretty dry up here too.’’ He added, “Sounds like a real good day to come home tomorrow.’’ Atlantis performed retrofire on October 18, and Ashby turned his spacecraft for re-entry. As Atlantis fell out of the Florida sky it was struck by some of the strongest crosswinds experienced by any landing Shuttle. Ashby, the most experienced Naval aviator in the Astronaut Office flew his spacecraft to a perfect landing at KSC, touching down on the runway centreline at 11:44. His only comment at the time was “It’s great to be back in Florida.’’ Melroy commented on Ashby’s smooth landing after the flight saying, “We’re so proud of him we could burst our buttons.’’ Ashby saved his comments for the flight in general, commenting at the post-landing ceremony to welcome them home, “What an incredible adventure we’ve been on. As I stand here. I can’t help but think about all the people that helped us take the [S-1] Truss up there. It’s been an amazing team effort.’’ British-born Sellers, who had just completed his first flight in space, called ISS an “Island in the sky that is a completely different place that has different rules. It was an experience like nothing I’ve seen or even dreamed of before. Things float. You’re climbing underneath structures like a spider underneath a gutter. It’s a magical place.’’

At a post-flight press conference James Wetherbee, Commander of STS-113, which would fly a similar flight to ISS in November, commented, “It was great to see them pull off the mission so successfully. That makes us feel a lot better and we’re that much more prepared.’’

With Atlantis gone, the Expedition-5 crew had returned to their daily routines. On October 24, Whitson and Korzun put the SSRMS through the manoeuvres that would be required to install the P-1 ITS, which would be delivered by STS-113 in November. That flight would also carry the Expedition-6 crew to ISS. In the same week Whitson brought her experiment programme to an end, in preparation for the Expedition-5 crew’s return to Earth. During the same period flight controllers in Houston up-linked new software to the three systems computers housed in Destiny. This was the first major update to the software since the laboratory module had been docked to ISS in February 2001.

|

SOYUZ TMA-1, FIRST OF A NEW CLASS

|

SOYUZ TMA-1

|

|

COMMANDER

|

Sergei Zalyotin

|

|

FLIGHT ENGINEER

|

Frank de Winne (ESA, Belgium)

|

|

FLIGHT ENGINEER

|

Yuri Lonchakov

|

|

Soyuz TMA-1 was originally scheduled for launch on October 28, 2002, but it was not to be. On October 15, 2002, a new version of the Soyuz-U launch vehicle, carrying a “Foton” satellite, was launched out of Plesetsk. The launch failed and the vehicle fell in a nearby forest killing 1 soldier and injuring 20 other people. The failure was later identified as being caused by contamination in the hydrogen peroxide system. As a result of the failed satellite launch the Soyuz TMA-1 launch was delayed on October 18, and rescheduled for October 29.

Soyuz TMA-1 was the first of a new class of Soyuz spacecraft, with the new Descent Module interior arrangement to facilitate couch frames designed to be adjustable to allow them to carry taller and heavier, or shorter and lighter than average crew members. The new arrangement had been developed after NASA recognised that the restrictions demanded by the standard Soyuz TM spacecraft meant that many American astronauts would not be able to serve on ISS Expedition crews as they would not be able to squeeze into the Soyuz TM CRV in the event of an emergency return to Earth. The new Descent Module also had improved instrumentation and avionics.

The new spacecraft was launched from Baikonur at 22:11, October 29,2002. Ten minutes later Soyuz TMA-1 was in orbit with its antennae and photovoltaic arrays deployed. Unlike on previous occasions, the Expedition-5 crew did not transfer Soyuz TM-34 from Zarya’s nadir to Pirs’ nadir before the launch of the replacement Soyuz. After following the standard 2-day rendezvous, the Soyuz docked to Pirs at 00: 01, November 1. Docking took place over central Russia and was monitored by the Expedition-5 crew inside Zvezda. Whitson described the rendezvous:

“Although the timing for the Soyuz arrival and docking was based on lighting and communication] coverage, it seemed to be choreographed for aesthetic purposes. I was using our new camera at the end of the S-1 Truss to film the docking. I was trying to find a tiny speck of light (we were in eclipse) in the general direction of the approach. I saw a brighter than normal ‘star’ and zoomed the camera for maximal magnification… As the Soyuz capsule began to fill my video monitor, the sun began to peek around the edge of the planet, making that incredible royal blue curvilinear entrance. Alpha [ISS] and the new Soyuz capsule were soon bathed in brilliant white light from the sun. While the Earth below was still dark, the Soyuz made contact and became our new rescue vehicle. Valeri and Sergei had

|

Figure 28. Expedition-5: The Expedition-5 and Soyuz TMA-1 crews pose together in Zvezda. (rear row) Peggy Whitson, Yuri Lonchakov, Sergei Treschev. (centre) Sergei Zalyotin, Frank De Winne. (front) Valeri Korzun.

|

a close-up view of the docking from the Service Module (SM). From the nadir windows in the SM it is possible to see the docking compartment, which extends below from the forward end of this module. In other words, the new Soyuz docked about 2 meters before their eyes.”

Following pressure checks the hatches between the two spacecraft were opened at 01: 26. After a safety briefing the three cosmonauts were welcomed aboard ISS. Over the next week, de Winne conducted his own experiment programme related to genetic engineering and the effects of microgravity on genes. The cosmonauts also performed protein crystal growth and materials processing experiments. Having swapped their couch liners with those of the Expedition-5 crew the Soyuz TMA-1 crew undocked Soyuz TM-34 Zarya’s nadir at 15:44, November 9, and manoeuvred clear of the station. Following retrofire Soyuz TM-34 landed in Kazakhstan at 07: 04, November 10. Soyuz TMA-1 was left docked to Pirs. It would serve as the ISS CRV for the next 6-months.

Whitson wrote:

“After the Soyuz undocked, we were able to watch as it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere, about 2 orbits later. The ground control team had provided instructions of where to look in order to see the spacecraft, and since it was during the eclipse, I shut off all the lights in the [Destiny] lab to watch from the window there. The thing I noticed first was what appeared to be a milky white contrail in the darkness. It brightened and the Soyuz became visible as it began to glow from the heat of re-entry. The Soyuz consists of three parts, the engine section, the ‘living compartment’, which is not any larger than a subcompact car volume, and the cramped descent module, sandwiched in between them. I was surprised to actually see ‘razdalenea’ (separation) of these three modules. The three glowing pieces separated, and the engine compartment and the living compartment trailed behind the descent module and began a fiery disintegration, looking much like a bright orange 4th of July sparkler. The central portion, the descent module, has a heat shield to protect the vehicle from the high temperatures (on the order of 3,000°F) generated during re-entry. We were able to see the descent module for a few minutes after separation, before it seemed to be swallowed up in the cloudy darkness below. About 4 hours after separation from the station, the taxi crew had landed in the cold desert of Kazakstan.’’

On November 10, the Expedition-5 crew waited in vain for the launch of STS-113. Following the cancellation of the launch attempt, Whitson pointed out to flight controllers in Houston that the crew had been rationing their drinks to make them last until Endeavour’s arrival at ISS. With the Shuttle’s launch delayed for one week she pointed out that the crew would run out of drinks before the Shuttle arrived. She asked for, and was given permission to take additional drinks from the equipment already delivered to the station for the Expedition-6 crew. She also sought permission to commence the Expedition-6 experiment programme, as the

Expedition-5 crew had completed their own science programme and packed away the equipment they had used.

A report entitled Assessment of Directions in Microgavity and Physical Sciences Research at NASA by the National Research Council’s (NRC) Space Study Board was made public on November 6. The report praised the advance in NASA’s microgravity research programme since its beginning during Project Skylab in the 1970s. It said that the present programme consisted of five areas

• biotechnology

• combustion

• fluid physics

• fundamental physics, and

• material sciences

all of which were threatened by the budgetary restrictions placed on ISS by mismanagement and the Bush Administration’s restrictions, including the limiting of the Expedition crews to just three people. The report advised NASA to maximise microgravity research both on ISS and in laboratories on Earth.

On November 8, NASA announced plans to alter their FY2003 budget request to allow for the implementation of a new Integrated Space Transportation Plan (ISTP), including plans for the Orbital Space Plane CTV/CRV. In order to fund the ISTP NASA had entered an amendment to its $15 billion FY2003 budget. Of this $6.6 billion would be assigned to the “completion” (Core Complete) of the construction of ISS by 2006. Over the next four years, the OSP would consume $2.4 billion, with the first flight taking place in 2008, carrying up to ten crew members to ISS. A further $1.6 billion would be spent on Space Shuttle enhancements allowing it to continue flying through 2012 and possibly up to 2020. In order to bring ISS to Core Complete in 2006, NASA would spend $15.2 billion by adding a fifth Shuttle flight to the annual launch manifest.

As if to prove that there was an urgent requirement for the proposed OSP, Yuri Koptev, head of Rosaviakosmos, reported that the Russian space budget for FY2003 would not increase over that for FY2002, with no allowance for inflation. Koptev stated, “The problem is that our legislators wonder why they need to set aside the same amount or more for space if our partner countries have cut their ISS budgets.’’ The Russians asked the International Partners to assist with the funding for the new Soyuz TMA spacecraft, stating that production might be delayed, or even brought to an end if no assistance was forthcoming. One suggestion put forward by Rosaviakosmos was to stop flying Expedition crews to the station and evacuate ISS. NASA made it clear that they would not consider that option, saying that, even if Russia stopped flying cosmonauts to the station on Soyuz spacecraft, NASA would continue to fly Shuttle construction flights, involving occupation of the station for a few days at a time. (The original Space Station Freedom, without the Soviets/ Russians, would have been constructed with crews only visiting the station on construction flights and not permanently occupying it until the final element, the Habitation Module, had been installed.)

One anonymous Russian source even suggested that if Russia alone was to maintain its ISS budget at the original level, in order to keep its contractual agreements to supply Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, then control of the programme should be passed from America to Russia. This naive view overlooked the millions of US dollars that America had given Russia to keep them in the programme from the beginning and the vast sums that America paid to support ISS operations. The same Russian source also naively suggested that Japan’s delaying completion of the Kibo science module threatened that country’s political relations with America and the ESA member states.

Meanwhile, the Russian Channel-1 television station had paid an original $20 million to Rosaviokosmos to begin funding a competition to place a journalist on ISS during a Soyuz taxi flight in October 2003. International journalists meeting Rosaviokosmos’ strict health and fitness programme and passing the standard Space Flight Participant training programme would be applicable to take part in the competition. The entire selection and training competition would be filmed by Channel-1.

|

STS-113 INSTALLS THE PORT-1 ITS

|

STS-113

|

|

COMMANDER

|

James Wetherbee

|

|

PILOT

|

Paul Lockhart

|

|

MISSION SPECIALIST

|

Michael Lopez-Alegria, John Herrington

|

|

EXPEDITION-6 (up)

|

Ken Bowersox, Donald Pettit, Nikolai Budarin (Russia)

|

|

EXPEDITION-5 (down)

|

Valeri Korzun (Russia), Sergei Treschev (Russia), Peggy Whitson

|

|

The Pilot on STS-113 was originally to have been Christopher “Gus” Loria, but on August 14, 2002 Loria requested to be removed from the crew due to an unspecified injury at his home that had caused him to fall behind in training. NASA quoted their privacy rules as a reason for not giving further details at the time. Paul Lockhart, who had flown as Commander on STS-111, a similar flight involving ITS assembly work and an Expedition crew rotation took Loria’s position.

Likewise, the Expedition-6 crew had changed just 4 months before launch. It had originally consisted of Ken Bowersox, Nikolai Budarin, and Don Thomas. In June, Thomas was grounded because his combined radiation exposure over the long – duration Expedition-6 flight would take him beyond his allowed lifetime exposure limit. He was replaced by Donald Pettit, who would be making his first spaceflight. Pettit had been training as Thomas’ back-up since January 2001. Bowersox paid tribute to Thomas, “Thomas really, really wanted to fly long duration. We know this has been very, very hard for him. But he is a big part of our mission. Everywhere we go we see reminders of him.’’ Despite this compliment, Thomas did not contact the crew on launch day to wish them well.

STS-113 would continue the construction of the ITS with the delivery and installation of the Port-1 (P-1) ITS element to ISS. The P-1 ITS would be mounted on the opposite end of the S-0 ITS to the S-1 ITS, of which it was practically a mirror image. The flight would also deliver the CETA Cart-B, for mounting on the ITS in support of future EVA astronauts.

All preparations proceeded towards a launch on November 10, 2002. On that date, propellant loading had been completed when a problem arose with Endeavour’s oxygen system, which had allowed higher than acceptable amounts of oxygen to build up in the mid-body of the orbiter. The launch was cancelled and rescheduled for no earlier than November 18, 2002. De-tanking the propellants in the ET began the following morning and was completed before engineers entered Endeavour to rectify the oxygen system. That work required the payload bay doors to be opened while the STS-113 stack stood on LC-39. A leak was discovered in an oxygen hose located in Endeavour’s mid-section, where fatigue from normal use, coupled with a weak design had caused the problem. The affected section of hose was cut out and replaced. While engineers were carrying out that repair a work platform struck the RMS in its parked

|

Figure 29. STS-113 crew (L to R): John Lockhart, Michael Lopez-Alegria, John Herrington, James Wetherbee. These four were joined by the Expedition-6 crew on launch and the Expedition-5 crew during recovery.

|

position, alongside the payload bay door hinge. The thermal cover was ripped and the RMS’ laminated protective cover was scratched. The RMS was subjected to X-ray and ultrasonic inspections, which revealed an area of de-lamination on the arm. Tests were carried out in Toronto to see if the de-lamination would affect the RMS’ performance. Two sets of repair plans were established:

• For a repair to be carried out in situ at LC-39, resulting in a new launch date of “no earlier than November 22’’.

• For a repair if the RMS needed to be removed from Endeavour, causing the launch to be delayed until December.

At the same time the nitrogen flex hose located in the mid-deck, next to the failed oxygen flex hose, was also replaced.

The Expedition-5 crew spent their extra time in space packing and labelling experiment racks and ran through the SSRMS manoeuvres required to fit the P-1 Truss when STS-113 finally arrived at the station.

STS-113 was finally launched at 1950, November 23, 2002, and successfully climbed into orbit. NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe was in Florida for the launch. At the post-launch press conference he made the comment, “The maximum period of time [in space] we’ve hit as Americans is 196 days. That’s less than half the time needed for a one-way trip to Mars. And we believe in round trips at NASA.’’

|

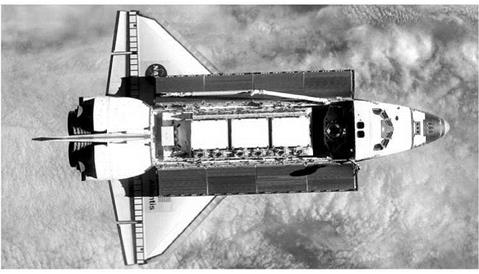

Figure 30. STS-113: Endeavour delivers the Port-1 Integrated Truss Structure.

|

After following the standard two-day rendezvous, Whitson told the approaching Shuttle crew, “You guys look pretty good out there.” As the Shuttle made a slow approach to ISS she told them, “You guys fly that like you stole it.” Wetherbee docked Endeavour to Destiny’s ram at 16:59, November 25. Following pressure checks the hatches between the two vehicles were opened at 18:31.

The Expedition-5 crew welcomed their visitors to ISS before Korzun gave them their safety briefing. Endeavour’s crew began transferring equipment immediately, including the Expedition-6 crew’s Soyuz seat liners and Sokol pressure suits. Bowersox, Pettit, and Budarin installed their seat liners in Soyuz TMA-1 and carried out pressure and leak tests on their suits before taking over command of ISS.

Asked to describe the crew exchange, Bowersox explained:

“Well, it just depends on who you talk to. On paper we’re supposed to go across, we’re supposed to put our seat liners in the Soyuz, we’re supposed to put on our Russian… Sokol entry suit, try them on, make sure that they’re leak-free, and then we’re supposed to do a test, all three of us together, to make sure that we’re ready to take over the Soyuz. Once we’ve done that, then officially we can be left on orbit. But if you talk to the guys who are there now, as soon as we show up, they’re going home… and our job is to figure out how we’re going to get back.’’

Korzun, Whitson, and Treschev ended their occupation as the Expedition-5 crew after 171 days 3 hours 33 minutes. They now became part of Endeavour’s STS-113 crew.

On November 26, Wetherbee secured Endeavour’s RMS to the P-1 ITS, secured in the Shuttle’s payload bay. At 10: 22, the bolts securing the truss in place were commanded to release and Wetherbee lifted the huge structure out of the payload bay and handed it over to the SSRMS operated by Bowersox and Whitson. The latter pair transferred the P-1 ITS up to the port side of the S-0 ITS and commanded the motorised bolts to secure it in place.

At 14:49, 30 minutes earlier than planned, Herrington and Lopez-Alegrla exited the Quest airlock to begin the first of three EVAs to connect the P-1 ITS to the S-0 ITS and the ISS systems. “How do you like the view?’’ asked Lopez-Alegrla, as they made their way outside. “The view is phenomenal, just fabulous. Life is good!’’ Herrington, the first Native American astronaut, replied.

Copying the procedures used to install the S-1 Truss in October, the two astronauts connected electrical cables and installed SPDs to allow for the quick disconnection of pipes in the case of a future emergency. They also released the locks on the second CETA cart, before removing the two large metal rods, called drag links, that had supported the P-1 Truss during launch. The drag links were secured to the P-1 framework. Herrington then returned to Quest to top off his oxygen supply before rejoining Lopez-Alegrla to install the Wireless video system External Tranceiver Assembly (WETA) antenna on Unity. The WETA would allow the pictures from an EVA astronaut’s helmet cameras to be received in the control centre without the need for a Shuttle to be present with the necessary antennae. The EVA ended at 21:35, after 6 hours 45 minutes. Mission control told them, “Great work. You’ve got a happy control team down here.’’

The two Expedition Crews spent the remainder of the day conducting hand-over briefings. Bowersox had described what he expected these to be like:

“There’s a lot of things that we just can’t cover in training because the actual configuration of the station is too fluid and too complex to track on the ground and to reflect in our ground simulators. So there’s a lot that we’ll pick up during the docked time frame that will help us early in the mission. It’s things that we just can’t train for: where the cameras really are, where items are located, where cables have been arranged, where people are sleeping, a lot of small things that you just don’t have time to cover in training.’’

November 27 was Wetherbee’s 50th birthday. The STS-113 crew spent the day transferring equipment between Endeavour and ISS, while the hand-over briefings continued between the two Expedition crews. Wetherbee, Lockhart, Herrington, and Lopez-Alegria also spent time in the afternoon preparing for the second EVA, while Whitson and Bowersox worked together to clear debris from the vent lines on the Carbon Dioxide Removal system in Destiny. Wetherbee and Lockhart also performed the first of three orbital re-boost manoeuvres using Endeavour’s thrusters.

|

Figure 31. STS-113: John Herrington and Michael Lopez-Alegria install the Port-1 Integrated Truss Structure.

|

November 28 was American Thanksgiving Day, but there was to be no holiday on ISS. NASA’s Bob Castle told a press conference, “It will be a very busy day for them. I suspect they will celebrate Thanksgiving some other day.’’

The second EVA began at 13:36, November 28, 45 minutes ahead of the time in the flight plan. Herrington and Lopez-Alegria connected two fluid jumpers to connect the P-1 ITS ammonia cooling system to the system in the S-0 ITS and the rest of ISS. Next they removed the starboard keel pin, a launch support. They used the CETA handcart to manoeuvre it to its permanent storage location on the P-1 ITS and secured it in place before installing a second WETA antenna on the P-1 ITS. Having removed and stowed the port keel pin they carried out the “get-ahead” task of releasing the launch locks on the P-1 radiator beams.

Herrington used a foot restraint mounted in the SSRMS to leave both hands free to allow him to pick up the P-1 CETA cart. Whitson and Pettit then swung the SSRMS so that Herrington moved across the front of ISS, passing across Endeavour’s payload bay, to secure the P-1 CETA cart on the S-1 ITS, next to the S-1 CETA cart. This cleared the P-1 CETA tracks for the SSRMS to move along them at a later date on its MT in order to extend that side of the ITS. Their final task was to reconnect a cable from the WETA mounted on Unity before stowing their equipment and returning to Quest. The EVA ended at 19: 46, after 6 hours 10 minutes. Space Station programme manager Bill Gerstenmaier told the media:

“It’s really been a textbook mission so far. It looks easy. It looks like it comes together without much trouble. That is totally counter to what really happens. It comes out so smoothly because of all the hard work we put in place.’’

During the end-of-day press conference Herrington described the EVAs, “The work is very difficult. Your hands get very tired. When the Sun goes down, you have this beautiful station illuminated in front of you. It gets incredibly dark, pitch-black, except the little spot your headlamp is aimed at. So you lose the perspective of what is around you.’’ He also admitted, “I was amazed at how massive the Earth is.’’

On the station, the hand-over briefings continued and the CDRA was working properly after Bowersox and Whitson’s repairs. The two crews shared a traditional holiday dinner courtesy of NASA’s unique home delivery service: Endeavour.

November 29 was a day of equipment transfers. Whitson transferred the PCG-STES Unit 7 to Endeavour while Bowersox transferred its replacement, the PCG-STES Unit 10, to Destiny. Lopez-Alegria and Pettit transferred the Plant Generic Bio-processing Apparatus (PGBA) from Endeavour to Destiny. The new equipment would allow researchers on the ground to observe plants being grown on ISS. During the morning Wetherbee and Lockhart used Endeavour’s thrusters to make a second boost to the station’s orbit. Whitson and Pettit also carried out troubleshooting tasks on the Microgravity Science Glovebox, following its failure on November 20.

During the afternoon Korzun, Whitson, and Treschev held a small ceremony to officially hand ISS over to Bowersox, Pettit, and Budarin. During the changeover

Korzun told the Expedition-6 crew, “We were so happy to live here, to work here… We will miss our space house.” He then told Bowersox, “I am ready to be relieved.” Bowersox replied, “And I relieve you.”

This was followed by a press conference, in which all ten astronauts took part. Bowersox told the conference that the Expedition-5 crew had set a very high standard of work that would be difficult to live up to. He added, “I only hope that my crew, Don, Nikolai, and I, will be able to work as well over the four, or however many months, we end up living on the station; hopefully more than four.”

Wetherbee, Commander of STS-113, told the new crew, “Expedition-6, it is your duty to sail on and disappear over the horizon, but return after discovering new land and make the world a better place.” It was a tall order.

Whitson admitted, “I do think I’m ready to go, but it’s been a kind of a gradual process. A month ago, when I started to pack, I was definitely not ready to go. My husband reminded me it’s much better to leave while you still want to stay, rather than the other way round. I’m happy to go, while I still wouldn’t mind staying here.’’ She explained how she had asked a NASA food specialist for a special meal on her return, “I asked if they would cook up a nice steak with a caesar salad with lots of garlic on it. I’m looking forward to getting some food that doesn’t come in a bag.’’ To go with her meal she wanted a cold drink, “We don’t have any carbonated drinks up here so I’m looking forward to that, and anything with ice in it would be nice as well.’’

Planning towards the third EVA began at 11:21, November 30, when Whitson and Bowersox prepared to command the SSRMS to attach its free end to the MT and then release its hold on the fixture on the exterior of Destiny. The transfer was delayed when the MT stopped 3 metres short of the intended transfer location. As a result, Herrington and Lopez-Alegria exited Quest at 14: 25 and began their EVA by searching for anything that may have caused the MT to stop. Harrington found a UHF communications antenna that had failed to deploy and had snagged one of the MT’s trailing umbilicals. He cleared the umbilical and deployed the antenna, which allowed the MT to continue on its journey, arriving at Work Point-7 (WP-7) at 17: 11. The MT was latched in place, and prepared to receive the SSRMS by 18: 00. The delay caused the astronaut’s EVA tasks to be re-prioritised and when they voiced the opinion that they could complete all of their tasks without using the SSRMS the walk-off from Destiny to the MT was cancelled. The two men completed all of their tasks, including the connecting of 33 SPDs at various locations around the exterior of the station. They also connected the Ammonia Tank Assembly umbilicals and reconfigured a circuit breaker on the Main Bus Switching Unit. Finally, they reconfigured the Squib Firing Unit on the P-1 radiator unit in preparation for their deployment in 2003. The EVA ended at 21 : 25 after exactly 7 hours.

December 1 was the final full day of joint operations. Herrington and Lopez – Alegria cleaned and stowed their EMUs and the tools they had used during their three EVAs. Wetherbee and Lockhart completed the third series of re-boost manoeuvres and the two Expedition Crews continued their hand-over briefings. With most of the two-way equipment transfers complete the two crews enjoyed some free time during the day to recover from their hectic earlier schedule.

|

Figure 32. STS-113: As Endeavour departs the station, the Starboard-1 Integrated Truss Structure is mirrored by the Port-1 Integrated Truss Structure. Following the loss of the solo Shuttle flight STS-107 and the grounding of the Shuttle fleet, the station would remain in this configuration for three years.

|

Wetherbee led his crew back to Endeavour on December 2, with the hatches between the two spacecraft being closed at 12:57. Before that happened, the two Expedition crews embraced each other. Bowersox told the three people he was relieving, “This is a big moment for us.” Pettit added, “We promise to take good care of the Space Station.” Korzun, the outgoing Station Commander, assured them, “Each crew does better than the last.”

With bad weather threatening Florida and a delayed landing likely, the Shuttle crew were told not to leave any of their remaining food with the Expedition-6 crew, as most crews did. Endeavour undocked at 15: 05, the same day and made a 90° fly – around of the station before manoeuvring clear. The Expedition-5 crew had been in residence for 178 days. Two Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) mini-satellites were released from Endeavour’s payload bay. The two satellites were tethered together and designed to test micro-technologies and nano-technologies during their three days of free flight.

December 3 was spent preparing for landing the following day. That landing attempt was cancelled due to heavy, low cloud and stormy weather over the Kennedy Space Centre. Likewise, the landing attempts on December 5 and 6 were cancelled due to rain and windy conditions in Florida. Endeavour finally came home to KSC, landing under Wetherbee’s control at 14: 37, December 7, after a flight lasting 13 days 18 hours 25 seconds. As Endeavour came to wheel-stop Houston radioed, “Welcome home to Valeri, Peggy, and Sergei after your half-year off planet. Great job.’’

Peggy Whitson was just 3 days short of taking the world endurance record for a female astronaut from Shannon Lucid. Even so, she did hold the new endurance record for an American astronaut on a single flight into space. The American record for total flight time accumulated over a number of flights stood at 196 days and was held jointly by Bursch and Walz following the Expedition-5 occupation of ISS. The Expedition-5 crew, who had been in space for 185 days, underwent the usual 45-day long battery of medical and physical re-acclimatisation tests that awaited all returning Expedition crews.

No one knew it on December 7, but this would be the last ISS construction flight for the next three years.