Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System, or GPS, is a network of satellites that enables anyone on Earth’s surface, or flying above it, to find out exactly where they are. The system belongs to the United States, but it is not the only satellite positioning system. Russia has developed a similar system, called the Global Navigation Satellite System

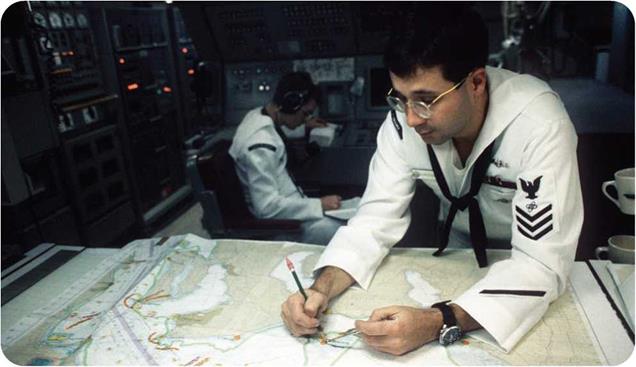

О The first satellite positioning systems were set up by the United States and the Soviet Union to give their submarines a way of figuring out exactly where they were during long patrols of the vast oceans. In 1989, this sailor on the USS Alabama checks information provided by GPS to pinpoint the submarine’s location.

(GLONASS). A group of nations in Europe and elsewhere in the world is developing a satellite positioning system named Galileo.

The Idea

When the first satellites were launched into space in the late 1950s, scientists were able to locate them and follow their movements through radio signals the satellites sent back to Earth. They soon realized that this might work in reverse. A satellite’s radio signal could be used to figure out the location on Earth of the radio that received it.

|

Three satellites would enable a radio receiver to calculate its position on the ground. A fourth satellite would enable the receiver’s altitude to be calculated as well. In order to have four satellites in view above the horizon all the time,

there would have to be at least twenty – four satellites orbiting the planet. A program based on this idea, the Global Positioning System (GPS), was developed by the U. S. Department of Defense.

there would have to be at least twenty – four satellites orbiting the planet. A program based on this idea, the Global Positioning System (GPS), was developed by the U. S. Department of Defense.

First, scientists had to prove that such a system would really work. Two experimental satellites, Timation 1 and Timation 2, were launched in 1967 and 1969. In 1974, a third experimental satellite, Navigation Technology Satellite 1 (NTS-1), was the first satellite to carry an atomic clock. Finally, NTS-2 was launched in 1977 to test all the systems and software before the first GPS satellite was launched in 1978. The whole network of twenty-four satellites was completed in 1994.

Myths from many different cultures tell of gods who come down to Earth to meet with humans. Some people claim that these stories reveal visits from space travelers in ancient times and that some ancient drawings show gods in spaceships or wearing helmets. Scientists dismiss these claims, however. Today, stories about aliens from other planets focus on unidentified flying objects, or UFOs. Since UFO sightings in Washington and Idaho gained great media attention in 1947, sightings of UFOs have increased dramatically. By the 1950s, some people were beginning to connect UFOs with religious and supernatural beliefs. Claims of UFO sightings are most common in the United States. The kinds of UFOs people report most frequently are flying saucers or moving lights.

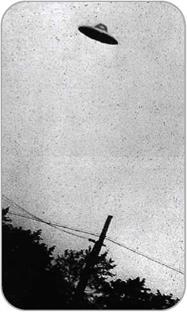

Myths from many different cultures tell of gods who come down to Earth to meet with humans. Some people claim that these stories reveal visits from space travelers in ancient times and that some ancient drawings show gods in spaceships or wearing helmets. Scientists dismiss these claims, however. Today, stories about aliens from other planets focus on unidentified flying objects, or UFOs. Since UFO sightings in Washington and Idaho gained great media attention in 1947, sightings of UFOs have increased dramatically. By the 1950s, some people were beginning to connect UFOs with religious and supernatural beliefs. Claims of UFO sightings are most common in the United States. The kinds of UFOs people report most frequently are flying saucers or moving lights. О A photograph from the files of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) shows what the photographer claimed was a UFO over New Jersey in 1952.

О A photograph from the files of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) shows what the photographer claimed was a UFO over New Jersey in 1952.

An aneroid barometer works in a different way. It is a sealed can with some air taken out. Atmospheric pressure squashes the can. The amount of squashing changes when the air pressure changes. These small movements are linked to a needle pointing at a press scale. Because they do not need a tall tube of mercury, aneroid barometers are much smaller than mercury barometers.

An aneroid barometer works in a different way. It is a sealed can with some air taken out. Atmospheric pressure squashes the can. The amount of squashing changes when the air pressure changes. These small movements are linked to a needle pointing at a press scale. Because they do not need a tall tube of mercury, aneroid barometers are much smaller than mercury barometers.