Onboard an Aircraft Carrier

A carrier is controlled from a tall structure, similar to an airfield control tower, known as the island. The island is on the starboard (right) side of the ship, leaving most of the deck clear for airplanes.

A carrier’s airplanes are usually stored on the hangar deck, from where

they are raised to the flight deck by an elevator. Aircraft may also be parked on the flight deck. The wings of many carrier planes can be folded to save space.

Specialized airplanes, such as the tilt-rotor V-22 Osprey and the AV-8B Harrier jump jet, have V/STOL (short for vertical/short takeoff and landing) capability, which makes them especially useful for ships. Fast jets, such as the Navy’s F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets, are launched by catapult to boost their speed for takeoff from the short aircraft carrier deck.

The carrier heads into the wind when planes are taking off or landing so that the force of the wind provides extra lift. Some naval aircraft have extra large

|

wing flaps to give the pilot good control at slow speeds. Some, such as the F-14, have variable-geometry wings. The pilot takes off and lands with wings in the extended position for slow flying, then moves the wings to the backward position for supersonic flight.

Landing on a carrier can be tricky for a naval pilot, even with modern radar and computer aids. There is a lot of ocean and only a narrow strip of flattop to aim for. As the plane touches down, a tailhook on its underside catches in one of four steel cables stretched across the deck, bringing it to a stop quickly. This device, essential to landing on an aircraft carrier, is called an arresting gear. Planes usually land on an angled landing section of the deck, situated on the port (left) side of the ship, so they can take off again if they miss the cables.

Carriers Today

Aircraft carriers are the biggest ships in the U. S. Navy. Today’s nuclear-powered carriers are able to travel up to 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) without refueling. Other countries operate aircraft carriers, too, although some of these are medium-sized ships operating only helicopters or V/STOL jets that can take off from a short “ski-jump” ramp and land vertically.

SEE ALSO:

• Aircraft, Military • Bomber

• Fighter Plane • Helicopter • VTOL, V/STOL, and STOVL • World War II

_____________________________________________ J

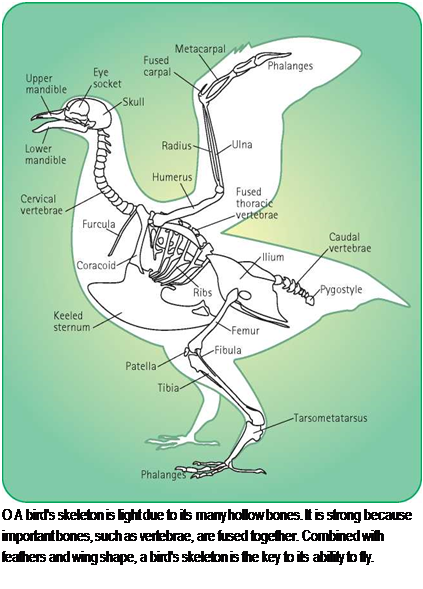

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.

September 30, 1907, they had a successful 12-mile (19 kilometer) flight. Five days later,

September 30, 1907, they had a successful 12-mile (19 kilometer) flight. Five days later,